Leigh & Quinns collaborated on Life Hacks last year, a very personal article about learning to play Netrunner. They return for this article about the 2015 UK Netrunner Nationals.

Quinns: I am slumped on the floor of the Birmingham Hilton. My head almost between my knees, I break into an orange by pressing my fingers into it until the skin splits. I begin eating. The flesh is both dry and watery in my mouth.

“I don’t know if I’ll make it,” I tell Leigh. Then a pause, weighing my next words with the pulp in my mouth. “And I don’t know if I want to play.”

I’ve been playing in the UK Netrunner Nationals for nine hours. I’m tired, of course, but more importantly some precious, competitive fibre inside me has snapped. Leigh is trying to repair it, mostly by talking to me about anything other than Netrunner. We discuss oranges, and the merits thereof.

Ruination is a hallmark of Netrunner tournaments.

It’s partially to do with how they’re structured. The first phase of any tournament is swiss pairings, where you and your opponent play both sides of a match of Netrunner (your corp vs. their runner, and vice versa). You play further rounds against people who’ve won as many games as you, so success only ever means tougher opponents.

It’s partially because the game of Netrunner is mercilessly tense. As the corporation you’re trying to hide your secret plans from someone who’s actively punching holes in your servers, invading your hand of cards and checking cards off the top of your deck. As the runner you’re trying to avoid impaling yourself on any number of corporate kill-cards and constantly staking huge amounts on what you think a face-down card might be. Can you afford to break into that server? Can you afford not to?

Worse than any of this is the idea of “Going to time”. Failing to complete your matches of Netrunner within the hour – for example, because you’re stuck in an adrenaline-laced slog of a game – means you score less points and often find yourself starting the next match with the last one still gummed to the inside of your head.

Your prize for doing well in Swiss? You become part of the elite cut to top 8 or top 16, who then play another tournament after everyone else has packed up. This time it’s double-elimination, meaning the top players keep playing until all but one of them has lost 2 games. The last player standing (or slumping) is the winner.

It’s worth mentioning that after the cut (a) amateur casters will get their cameras out and start to film matches and (b) your brain is pudding, leading to countless Netrunner finals online where commenters question why the best players in the world are forgetting rules.

Nationals was the biggest and longest tournament I’d been to by far, with 153 players competing in a massive marquee. I surprised myself by starting the day with a clean run of 6 wins and 0 losses. Netrunners who’d come up from London with me and Shut Up & Sit Down fans alike were slapping me on the back, whispering confidently that I was sure to make the top 16.

My fall had come in round 6 of 7. I’d been running against the Jinteki corporation’s Replicating Perfection division, a powerhouse of a card whose labyrinthine server infrastructure means you have to run their servers in a certain order. It’s a nightmare, and I’d have to be playing my very best.

Now, let me take you one level deeper.

At this point I’d been playing for seven hours and I became distracted by a habit of my opponent.

It’s common in card games for you to offer your deck to your opponent after you shuffle it, and they have the option of cutting it- dividing it in two, then placing one half atop the other. Theoretically this prevents cheating, but for most players it’s a silly ceremony. Some players will wrinkle their face when you offer your deck and make a magnanimous gesture, indicating they don’t care. This telegraphs trust and friendliness. Most players will give the deck a quick cut. Some players (especially those with a background in Magic: The Gathering, I’d find out later, a game which requires far more shuffling than Netrunner) will take your deck in their hands and shuffle it.

My opponent was a shuffler. Every time I had to give my deck a quick shuffle, he’d take it and we’d have to stop playing so he could shuffle it more. This was entirely within in his rights, and I shouldn’t have been upset.

Let me take you deeper again.

That’s my god damn deck he was touching. Throughout tournament season I’d become increasingly superstitious about my deck. Bear with me.

I had a ritual when I’d sit down with an opponent. I’d unroll my playmat, which was always held in place by two of my girlfriend’s hair bands, and pour out my tokens, which at some point had been joined by two AAA batteries that I didn’t want to remove for fear of losing my mojo. I’d stop shuffling my deck not after a requisite amount of shuffling but when I felt in my hands that my deck was telling me to stop. On two occasions that day I found myself whispering encouragement to my corp deck, which responded by giving my the exact cards I needed, when I needed them.

Imagine how I react, on a subconscious level, when someone starts shuffling it without my say so. Imagine my uniquely English rage: A porcelain mask of a face with these vermicular feelings wriggling about underneath.

Let me take you deeper just one more time.

Your deck in Netrunner is more than the cards it’s composed of. It’s the sum of your understanding of the game and the “metagame”, meaning the decks and cards you expect other people to bring to a tournament. Each card you slot into your deck must be weighed up against the other 44 cards in the deck, the other 400 cards you could be slotting in, and – in my case – the 6885 runner cards that 153 players would be bringing to Nationals.

My friend Baki lives around the corner from me. In his hospital-green kitchen we’ve spent many a night with my Gagarin Deep Space corporation deck between us, dismembered and face-up on the table. Sometimes talking, sometimes just staring, silent. Green tea cooling in glass mugs.

Nobody plays Gagarin. It’s a simple corp with an underwhelming power. To access a card in one of its interstellar servers, the runner first has to invest 1 credit. The entire Netrunner community passed it off as a “binder card”, something to file away until other cards are released that make it good.

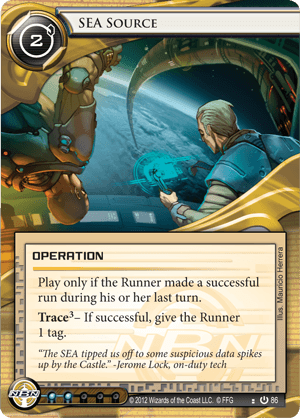

But Gagarin is precisely how I like to play Netrunner. It exaggerates every moment where your opponent doesn’t know what you’re doing, because it’ll cost them extra to find out. And if you can just edge ahead of them in this economic shell game, you can trace their location using a delightfully innocent card titled S.E.A. Source (Space Elevator Authority)…

…before blowing up their house.

But getting the balance right between economy, protection and kill potential was a nightmare. It always is.

“We are in the depths of the jank,” I distinctly remember Baki saying on one of those nights, as we experimentally sleeved up three Shell Corporation cards. These are tiny little corps within your corp that latch onto your servers like little blisters, potentially making you money. This was back in March, when I could almost never scratch out a win with the deck.

But you can brute force deckbuilding, if you have the time and attention, which is exactly what we did. You play the deck and you go with your gut. You play the deck ten times and learn which cards you hate to draw, strip them out and replace them with better guesses. You build sisters and brothers of your deck with different ideas and ideals and see if they work. And in doing this, you also improve your performance at tournaments, overcoming exhaustion because you can play the final form of the deck on autopilot. You know every card.

That’s not an exaggeration. On the day of Nationals, I could close my eyes and name 49 cards from memory. We all could.

Three days before the tournament I was sat in front of my TV with a wet cloth, cleaning flecks of dust and spit from my Gagarin deck’s black card sleeves, making her look nice for Nationals. Black, because Gagarin is a corporation that works in outer space. I always dress my decks nicely.

Again: Imagine how I felt watching my opponent shuffle my deck without my permission. Cloaking myself in a smile, mid-match, I asked why he did all this shuffling. If he really thought I was cheating. I questioned his etiquette. It was the only play of the tournament I’d end up wishing I could take back. If you’re reading this, shuffler, I apologise.

So I let the Shuffler get to me. I think I would have lost the game anyway, but it felt like I was playing poorly, which creates stress, which makes you play worse. This is known as tilt.

That match played like a door closing. The click of the lock came when my runner was unexpectedly placed on a corporate Blacklist. Suddenly the famous Levy University wouldn’t let me in to refresh my deck, and because my runner was so burned out I couldn’t even hack into the server containing the Blacklist and remove myself from the list. It was a rare, terrible sort of chokehold.

What stung wasn’t that I’d lost the game in a new way, it was that I hadn’t seen it coming. It was a crippling blow to my confidence. At that exact moment, a player from the London meta who’s known for being somewhat intense stood up at the top table and screamed the words “ANOTHER WIN!”

That was when I felt the snap. It was when my day turned from 7 hours of Netrunner into too much Netrunner. Smarting from two losses, I got launched down the tables into a scrum of players who weren’t going to make the cut. I picked up two more wins, but I couldn’t tell you anything about the games.

Which takes us to the floor of the Hilton, and me eating an orange with Leigh. I didn’t know if I’d make the cut, and even if I made it I didn’t know if I wanted to play.

Leigh: Everyone asked me why I didn’t play too. Six Swiss rounds, I said, was my maximum, and Nationals was supposed to have been eight. In the end it was just seven, and I said a few times, “well, if I’d known it was only seven, then I would have played” — the psychological difference between ordinal numbers is massive in Netrunner. It’s why a card that costs five credits to trash feels somehow massively more significant than one that costs four. It’s why Quinns’ Gagarin deck sneaks up on you, whittling away at you with a million tiny costs that seem too small to consider.

It’s the psychological part of Netrunner I like the best. I’m better at that part than the actual game. Good players will do the move that makes the most sense, and I am good at lying to them, with casual misdirections, about what I am doing. “I would have played if I’d known it was only seven rounds,” I told lots of people that weekend, apologetically.

I was, of course, lying. I was really just scared. There were maybe five other women in that room. What if I sucked? I’ve never played that long in a tournament before. I wasn’t sure I wanted to try. It seemed exhausting.

So I selected an equally-unfamiliar alternative: To spend the expo weekend in the role of Just A Girlfriend. I have never been Just Someone’s Girlfriend at a games event before; as a woman in video games I have rallied imperiously against the prospect of being Mistaken for a Girlfriend; at video game events everyone usually comes up to me and then I have to introduce Quinns to them. It was strange to stand at his shoulder; sometimes people who spoke to him did not seem to see me at all.

When he woke up early to go compete under some fearsome far-off tent, I stayed in bed. I slept late, and I ordered bruschetta to my room and I lay there playing Regency Solitaire and watching Jeremy Kyle out of foreigner’s curiosity. I felt like a skinchanger. It felt wrong. I decided to get up and at least try to meet him for lunch, to see how he and our pal Chris were doing, if they needed any snacks.

As I wandered nervously in and out during the day it quickly became clear that Quinns was doing very well, and that having him come top 16 was materializing as an actual possibility.

I confess that I had been sort of hoping he wouldn’t make it. Leave the rarefied air of the top tier to the people who never have any fun, and let us and our friends spend a relaxed and chatty night in the hotel bar.

“I almost don’t want to make it,” he declared, “so that I can hang out with you later.”

He said this a couple times. He also often said, “If I make top 16, I probably won’t continue. It’s just too much.”

I know his facial expressions. I knew he would continue. I put a tiny flower in his buttonhole but refused to say it was for “good luck.” By the end of the day’s games I took him away from everyone so he could eat an orange. Because here’s the thing: it’s not just the rounds upon rounds that get you. It’s the ruminating that everyone does in between, shuffling around outside for a gasp of fresh air, or a cigarette break.

It’s that damned question: “So how did you do?”

There will always be some story you have to tell more than once on your ten-minute break about how you made a guy run into this or that. And then it’s did you hear about what’s his name who did the other thing in his game. And how if you’re doing pretty badly, you kind of have to pretend that you’re not, just to keep your spirits up. It’s the psychological parts. I know the psychological parts.

“Hey Quinns,” someone we don’t know came up while my tall boy curled himself around a cigarette, staring into the middle distance like a boxer between rounds. “I just want to tell you that –”

“It’s not a good time,” I intervened sharply. If that was you, I’m sorry.

I hid Quinns on the floor of some board game-branded hallway of the Hilton Metropole and I talked to him about oranges. I listed every fruit that I don’t like (oranges, with their fibrous sheaths are vile, as are bananas, with their unreliable texture variances, their body strings). I talked about anything except Netrunner until the color returned to his face.

Sometimes people walked by and looked at him as he ate his orange, like they wanted to come and say hello to Quinns from Shut Up & Sit Down. I wore a discouraging face — probably a terrifying face. I didn’t want you to come and say hello. If that was you, I’m sorry.

By the time the orange was finished he no longer looked like someone who might have made Top 16, but we decided to walk back and read the placements. “You’ve got to see,” I said.

“Yeah,” he sighed.

There was an aisle of people returning to the tent, an aisle of people leaving it. Everyone we passed on our way to the tent said, “Congratulations, Quinns.”

He’d made it. “How do they all know,” he bleated miserably, after a while.

We do it for games like this.

My first match of the Top 16 was against 2014 UK National champion Dave Hoyland, his runner against my Gagarin. Never mind the tournament’s actual prize support. When you love a game this much, getting to go head to head with a great player is a prize in itself. Rocky is not a movie about a boxer who wants to win. It’s a movie about a man who, just once, wants to stand with the best.

I could tell you truthfully that I was tired, or scared, or didn’t expect to win, but that would be like talking about the weather during an eclipse. When you’re quite this sodden with adrenaline there is nothing except you and the game. It’s common for elimination rounds of Netrunner to gather a crowd, but the contestants only notice once the match is over.

There’s a play at 08:16 I want you to see. Dave plays a Legwork, which is a run on the corp HQ (their hand of cards) that allows the hacker to see 3 cards if they get in. I have 4 cards in hand at the time, so there’s one card he won’t see. That card is a Scorched Earth. It’s the card that blows up his house.

This explains why at 15:00, Dave walks past a piece of Intrusion Countermeasures I have installed known as a Data Raven, which can tell the corp where the runner lives. Dave’s made the calculated risk that I won’t have access to enough meat damage cards to kill his hacker.

But I do. I do the maths. I double check the maths. I feel a wave of relief that is nauseating in its intensity. This causes me to snap out of the meditative state I’d been in for quarter of an hour, and suddenly every question I ask myself is something I have to force through my head, like delicate packages through a narrow letterbox. “Can he get out of this?” “Do I have enough credits?” “My god, where did this crowd come from?”

At 15:58, you can see me steeple my fingers. This is my one visible response I allow to my heart, which feels like it will slip its restraints and go slithering into my stomach.

At 16:14, I begin the turn that kills Dave. You can tell how scared I am because I’m moving my hands like a surgeon. Every gesture is considered. If I just take this step by step, nothing can go wrong, right?

At 16:32, when I’ve played 1 of the 2 Scorched Earths required to kill him, you see Dave put his hands on his chin. The only visible response to his own fear.

When Leigh and I wrote about learning Netrunner, we said the real reward was a wild new kind of communication, both in playing the game and talking about it. There’s a joy in learning a new language.

The reason you take Netrunner seriously (or any game seriously) is because of the conversations you can have.

I rolled up my playmat, left the marquee, and flashed a waiting group of friends a shaking thumbs-up.

Leigh: After he beat that guy, I got really scared. Within an hour, I would reach Peak Girlfriend. Just standing there ambiently on the verge of tears. Snapping IT’S NOT A GOOD TIME to everyone outside, drinking and smoking nervously, making sure he had quiet and stupid hours in the lengthening dark to wipe his servers with my frantic prattle. Tell me about the book you read on the train. I’ll tell you about what was happening on TV this morning.

“So do you actually play Netrunner, or are you just soaking in the atmosphere,” a guy asked me. I was one of some twenty people crammed around the tables of the last people standing. It was this guy’s friend that Quinns was trying to beat.

I sat there whispering things under my breath like kill him honey get him scorch that fucker come on come on. I was the worst sport in the room. I Tweeted a picture of Adrian Balboa. Did Adrian ever yell things, in any of the Rocky movies? I couldn’t remember. Didn’t she kind of just sit there hopefully? I should be quiet.

The below video records my final, 18th game of the day.

I don’t know what I had thought was going to happen, once Quinns entered the Top 8. That he was going to win the entire tournament? I mean. Maybe I did hope that he would, for a minute. At the very least, I wanted to know how far he could go, and this long, bleak silence, where people I didn’t know kept stepping in front of me so that I would never be able to tell when, if ever, he had gained sufficient economic advantage to be able to kill his opponent, felt suddenly final and not enough.

But only for a moment. Then, you are tired, you are finished, and you made the top 8, and you can go to the hotel bar. I don’t know if I had ever been that proud of him. I don’t know that I ever saw him that proud of himself.

There was some debate about what Quinns was going to do with his Top 8 playmat, once he finally had it (he prefers plain playmats, as opposed to the official ones). He said he might want to offer it as a prize in one of his own London tournaments. The guy from our meta who had shouted ANOTHER WIN said to him: “Quinns, listen to me, I want you to seriously consider keeping it. “

“He doesn’t need to show off,” I said.

ANOTHER WIN ignored me and said “No Quinns, seriously.”

“HE DOESN’T NEED TO SHOW OFF,” I said again, more loudly. Peak girlfriend. I went there. If you were there, I’m sorry.

(In the end, Quinns chose to keep the playmat.)