Thrower: Do you find numbers scary? Do you dread the pointy 1, the razor-sharp 7, the misery of an unsolved sum? If you do, you’ve probably realised that most board games are just fearsome equations wearing friendly grins.

Designers, however, understand this, and more. They welcome it, glory in it, roll in it like pigs in mathematical mud. Because it’s what they use to build the foundations of something fun, yet something real.

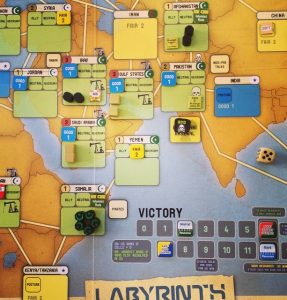

Take Volko Ruhnke, designer of contemporary wargames Labyrinth and the Counter-Insurgency (or COIN) series. “Most board games and video games that are about something are models,” he told me. “Trading games, railroad building games, shooting games, strategic war games. They all communicate the game designers’ model of certain aspects of human affairs.”

Models aren’t just pretty things. Like any art, they can teach you on the sly while you enjoy them. “A historical board game designer typically will not do much original historical research,” Ruhnke explained. “Instead, they read lots of historians’ books on a historical period, then express the models underlying those experts’ writing in game form.”

For most of the games we love, these models represent conflict. Or perhaps impressing Renaissance nobles, depending on your taste. But you can model lots of things, including the dark and controversial. That’s what interests Ruhnke above all.

“Politics concern the affairs of millions of human beings deciding who gets what when,” he said. “These affairs are so complex that we must simplify them to interpret them. When we think about politics, the dynamic interactions of millions, the filters that we use are mental models, either explicit or intuitive. When we debate politics thoughtfully, we are discussing competing models.”

Anyone who’s seen the yah-boo style of British politics will spot right away what he’s on about. It’s a competition, like a sports event with less jockstraps and more corruption. “A political model must include the interaction of human incentives, capacities, decisions, and outcomes leading to new decisions,” Ruhnke observed. “That equals a game. Victory conditions, things that players can to do against one another, player moves that affect something, winners and losers.”

Ruhnke, though, is like a class teacher who also wants to be your best friend. He doesn’t just want to entertain you. He wants you to learn too. “Experiencing a game, players can then decide if they buy that model,” he told me. “If so, then perhaps someone’s political point is made. Far more importantly, if players do not completely buy the model, they have refined or at least made more explicit their own model of the world in contrast with that in the game.”

You can see this thinking in his game Labyrinth. “It’s not about points like ‘we should do this not that'”, he explained. “My hope is that it contains far more useful points such as ‘what do the Jihadists want’ and ‘why do they think terror helps them’?”.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. “The game’s model can enable players to experience in a simplified way the interactions of many aspects of politics,” he explained. “To address the question ‘how can these factors interact to either diminish or feed anti-Western terrorism?'”

But if it’s about juggling as many different variables as possible, surely a computer could do it better? That’s their job: to stockpile as much information as they can in their hot silicon brains and use it to spit out answers. They’re good at it, too. It’s the reason many (heretical) wargamers have come to prefer digital games to tabletop ones.

It’s no surprise that Ruhnke disagrees, but he disagrees with considerable vehemence. “There are major advantages to physical games over digital, not only in exploring but especially in conveying political themes. Returning to the concept of game as communication of a model,” he continued. “I am transported in playing a game because I can operate the model myself, as if I were in that role in real life. I can take command of Caesar’s legions and subdue the Gauls.”

At this point I’m imagining a wargame based on Asterix. But Ruhnke shakes me out of that pleasant reverie. “I could try to improve on the historical performance of storied leaders, or try out different strategies. Perhaps demonstrate to myself that historians’ critiques of a leader’s strategy are either well or poorly founded. I am not just watching: my decisions either win or lose the day.”

Is that still not true of video games? “If my inputs as a player do not produce outputs in the game that I can believe, I am unlikely to feel the role,” Ruhnke explained. “If play does not bring me to understand the game’s model, I will feel less like the historical leader. That leader, after all, understood his or her own real world, maneuvered within it, and did great things.”

I’m not so sure many players would want to walk a mile in Hitler’s shoes. However, it’s not just about the feels but the thinks, too. “That’s a big hitch with digital games. They are inferior to physical games in showing how and why the player’s inputs produced the outputs that they did. I cannot really see the model, nor access it to modify to improve to my understanding of history or the world.”

That neatly explains why Ruhnke’s games always contain thick playbooks, daunting with detail and diagrams. It’s so players can see what he’s presumed, what he’s simplified, in building the model. But making complex things look simple has its dangers. That’s the root of extremism.

Labyrinth, for instance, wants to tell a story about how terrorism starts with the corrupt governments of so many Arab countries. Some might say that all the troops, bombs and spies we dropped there over the decades could have something to do with it, too.

Ruhnke stresses that this is dealt with in other aspects of the game. “Labyrinth models the balance of so-called ‘soft power’ versus ‘hard power’ tools against jihadism or to affect Muslim governance.” he explained. “The game’s premise is that this differs among countries and administrations outside the Muslim world and shifts back and forth over time. One example is the shifting relative postures of Paris compared to Washington from 2001 to now on the use of military force to affect Arab regimes.”

One real-world result of these shifting sands was the Arab Spring. A bright moment of people getting together and deciding they could do things better by themselves. Few predicted it, and it’s not allowed for in Labyrinth. Until now, at least. “Another designer, Trevor Bender, has offered us an expansion to the original game,” Ruhke revealed. “Called ‘Labyrinth: The Awakening‘, it adds not only a new event deck for 2010-2015 but also new game mechanics covering these phenomena”

You might think Ruhnke would regret failing to include this in his game. But he’s unabashed. “I actually have little faith in the ability of games to predict human affairs,” he told me. “The reasons for my skepticism are the complexity and non-linear outputs of decisions made by so many human individuals.”

So what, then, are they for? “Political games are best for the support of discourse, training, and education,” Ruhnke explained. “Endeavors that help us prepare or position for the future even if they do not predict. Used appropriately, simulation gaming of human affairs such as politics can help us think more fully and deeply about future possibilities.”

We’re back in teacher mode. “It can open scenarios that we had not considered,” Ruhnke continued. “It can raise questions about assumptions that we had not even realized that we held. It can start conversations among us about how political affairs work and where they might go.”

It’s this last point which I think is most important. Games like these give us a unique chance to live in someone else’s skin. To understand why other people agree with views that seem baffling, even offensive. Ruhnke agrees. “It makes political conversations more productive,” he said. “Because they are structured around a commonly experienced but not necessarily commonly accepted model: a game.”