Paul: I think I can trace my excitement for custom dice right back to my earliest gaming experiences. Dice were supposed to be uniform, six-sided things that counted from one to six. The moment I saw that you could put other things on dice, my world was turned upside down. Icons? Pictures? Why stick to just six sides? Any shape you roll could be a die! What was to stop me shaving numbers into the dog’s fur and tempting her to roll about the hall floor to decide our gaming fates? Nothing, friends. Nothing.

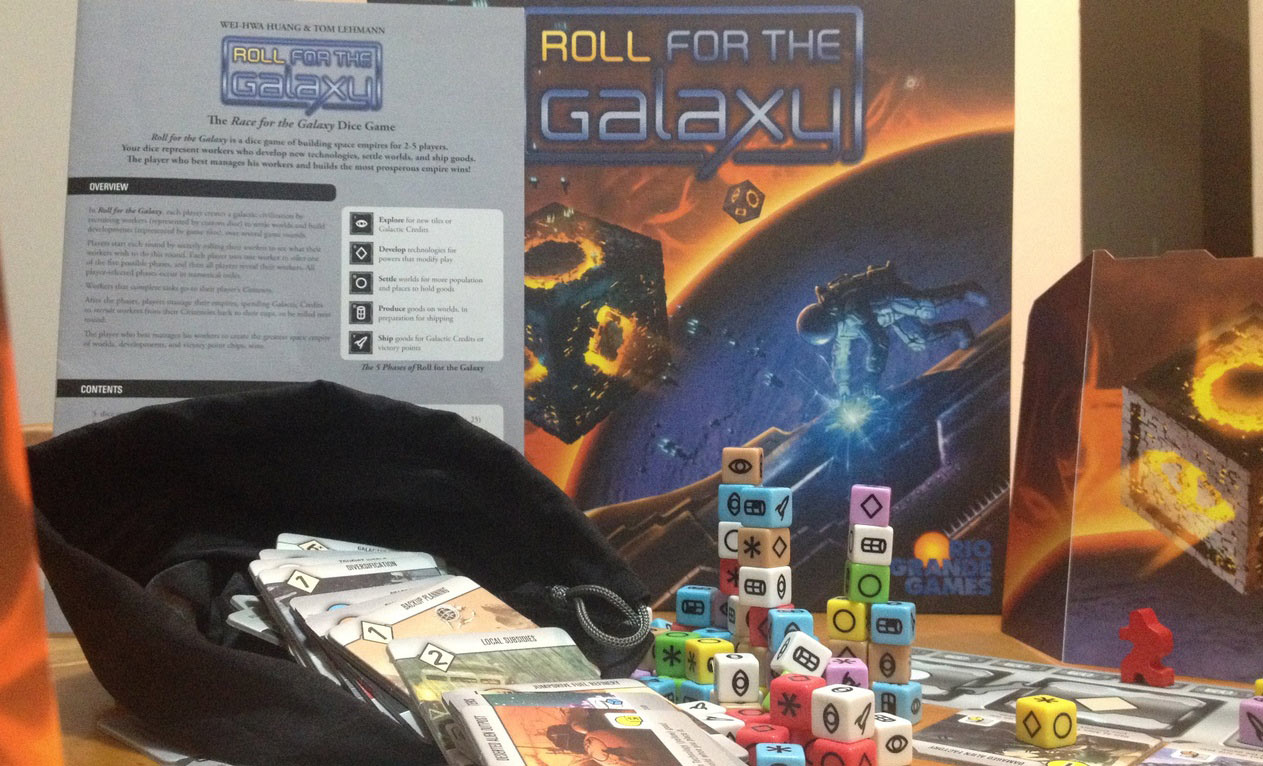

The first time I heard about Roll for the Galaxy’s 111 multicoloured custom dice I had to be sedated. I don’t actually remember much of the day but Matt says they had to call an ambulance and I recall Quinns, Brendan and Leigh visiting me in a facility specially constructed and arranged to avoid reminding inmates of the platonic solids. Thing is, in that place we still had our black market deals that the staff didn’t know about. Ten pounds to touch a D12. Forfeit an evening meal to roll some X-Wing attack dice.

Oh yeah, Roll for the Galaxy. I’d better tell you about it.

The first time I got my hands on Roll for the Galaxy was last year and it took me a little while to form a cautiously optimistic but ever-warming opinion. It’s very obviously the cousin of Race for the Galaxy (one star of our Sci-Fi Special). It’s also a game where turns are made up of different phases that may or may not trigger depending upon whether players choose them. The aim is also the same: score victory points by settling a cornucopia of alien worlds and trading the many colourful goods those worlds drop like so much throbbing, chromatic fruit.

But while Race for the Galaxy is a card game, Roll for the Galaxy is all about both dice and tiles. Those tiles are big, thick, chunky things like slabs of rich chocolate (but don’t eat them), while those dice are vibrant, juicy handfuls of gleaming bon bons (don’t eat those either). I may as well admit this right now: I like touching Roll for the Galaxy.

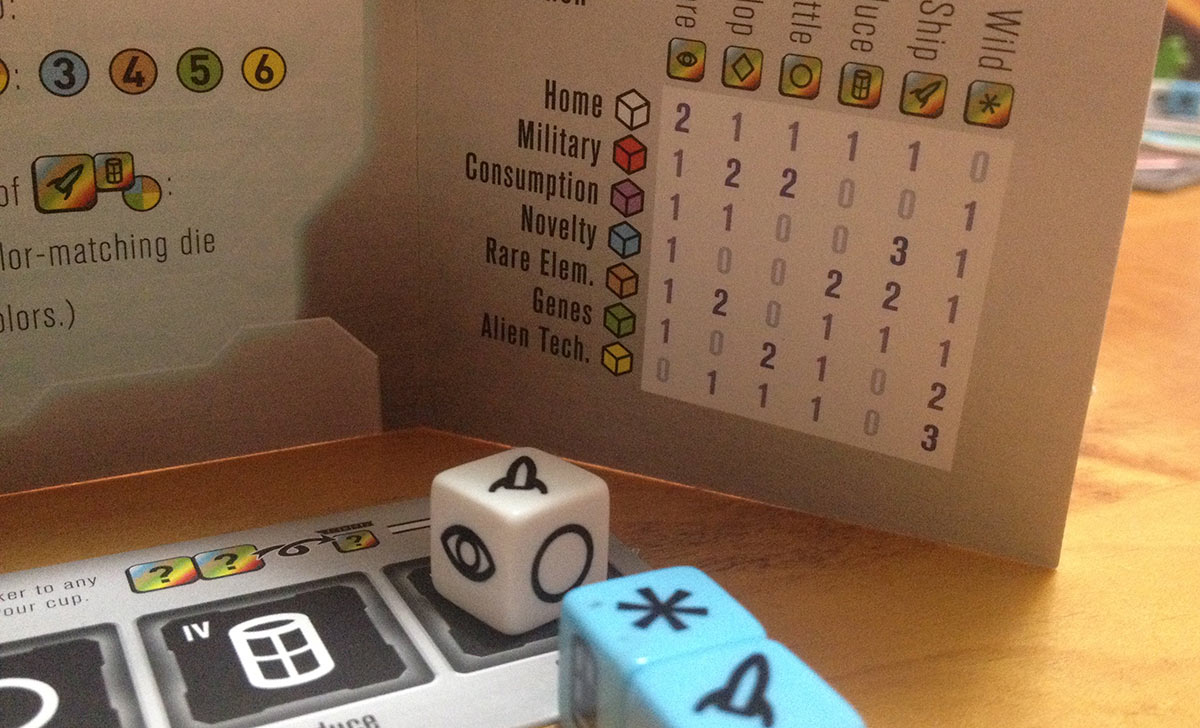

So here’s how it works. Like Race, Roll has distinct phases that correspond to actions you can perform. Those are Exploring (which I’ll get to in a moment), building interstellar Developments (space infrastructure), Settling planets (making new homes), Producing space goods (splicing genes; mining minerals) and Shipping goods (turning that stuff into cash or victory points). Each turn, every player secretly selects one of these by rolling cute white dice behind the safety of a cardboard screen, mumbling to themselves in their indecision and then assigning those dice in what is something of a pan-galactic compromise.

Y’see, one of those dice must pick a phase and, depending on how lucky your rolls were, that’ll either be what you wanted to do or what you can at least stand to do. It represents what you’ll definitely get to do this round and that die gets plunked on your Phase Selection Strip (Even that sounds sci-fi. “CAPTAIN, THEY’VE HIT OUR PHASE SELECTION STRIP.”). The others are then arrayed below the strip according to what they rolled and they count as potential actions, things you might still be able to do if someone else rolled and chose one of those phases. Potentially, you could end up doing an awful lot of things in just one turn, though that depends as much on your on good judgment as it does luck of the tumble.

After you’ve all assigned dice, those screens fall away like the shields on an ailing Star Destroyer and you get to see exactly what everyone’s chosen. Kathryn is going to explore! Benjamin is shipping! Jean-Luc had decided to trade! Maybe that works out well for you because, even though you didn’t choose those, several of your dice still turned up these results. Or maybe you’ve doubled up, or worse, everyone’s trading and nobody’s boldly going. So many lonely dice left floating in the void.

At the start of the game, you can always burn one die to reassign another but, depending on what tiles you develop or settle, you may be able to assign more or you may find yourself rolling sexy new coloured dice, perhaps with fancy wildcard symbols. Not only does this give you some freedom about where you place these little cosmic chancers, it also means you can stack a bunch of them up under the same phase and go all out space crazy.

Wait. WAIT. First, let’s focus our telescopes on what happens when you have one die on a phase. Let’s talk about the exploring that I teased you with a few light years ago. Let’s talk about black holes.

While Race gave you a gigantic deck of cards that represented all the possibilities of outer space, Roll gives you a cavernous bag to reach down into. From within this dark, silent and mysterious anomaly you retrieve the tiles which are going to be your planets or developments but, in an act of quantum cruelty, your grasping of these tiles determines what they are. Each is double-sided and offers you either a development or a planet, many of which might work together in wonderful unison but which can never meet. The moment you take that tile, that unique tile that is unlike any other in the game, you choose which it will be, placing it in a build queue in front of you, ready for your developers or settlers to claim.

If you had just one die assigned to exploring then you, quite logically, take just one tile. But if you had two, you’re a double dipper. If you have four dice, then dive in four times. This is what you can do with all of Roll’s phases, and you will do it as the game progresses. Each die you assign to developing or settling gets plopped onto the tiles you’ve bought this way until you equal their value, so it’s in your interest to hurl great handfuls of dice their way to complete them as soon as you can, not least because those dice sit inert upon those tiles until the job is done.

And here’s another thing about those ever-growing pools of dice that become larger and more colourful as you collect more planets: they cycle. These dice represent resources and, as you use them, they’re moved to your player board in front of you and need to be purchased again before they can be moved back into your pool. If they didn’t get played this turn, that’s just fine, they go back anyway, but the moment you use them you’re exhausting them. You gotta pay to play again and, while you’ll always get at least one space dollar per round to do this with, you can also get cash by finding the right planets or developments, by shipping goods for money rather than victory points, or by cashing in exploration dice instead of using them to make First Contact.

So I’ve talked a lot about rolling dice, about getting more dice, about rolling more dice and about reaching into a huge black bag of possibility to clutch at chance and circumstance. I’ve talked about those things and here we are, you and I, facing off across the Captain’s table and you’re telling me that Roll for the Galaxy is so much a game of chance, but it’s really not. It’s a game about coping with chance. That’s why I like it so much.

When you roll your dice and choose your phases then, sure, some compromise can happen, but burning one die to assign another means you can almost always have something you want if you can stomach that small sacrifice. Choosing to make a planet or development from what you drew from the space-bag is a big decision, but always your decision and, while it’s not the most efficient thing to do, you can also toss these away if you change your mind later. After you commit dice, it’s always your choice which of those you buy back first (each type of dice has different phase distributions) and, naturally, you’ll be carefully curating your growing tableau of tiles to make sure they gift you more dice, hiccup money and perfectly compliment one another like sexually frustrated astronauts trapped in a steamy escape capsule.

If you know Race for the Galaxy, all this may sound like some sort of alternate universe episode to you. There’s the huge set of unique planets, the turning all sorts of goods into victory points, the critical choice about which phases to pick (with all the second-guessing your opponents and their plans) and the importance of getting your own little economy going, but now everything wears a goatee. Well, okay, everything now wears dice. Dice sit on planets as goods. They sit on things you’re developing. They sit behind your screen, just gagging to break orbit.

God, I love them. It’s delightful to gradually assemble your own collection, just as it was in Quarriors. It’s delightful to build your own quirky sector of hard-working planets and watch them churn out novelty goods or alien artefacts or whatever else. It’s all delightful and I just adore Roll for the Galaxy. I really like where and how it introduces random chance. I really like how it still leaves the biggest decisions to players. I really like how it rewards careful planning but doesn’t punish you too much if you screw up, letting you throw stuff out of your build queue or simply reclaim dice if they were never used that round. I even really like its slim manual, much of which is just clarifications.

I very much recommend Roll for the Galaxy and not only do I wish I’d tried it sooner, I wish I’d tried it more and I wish we’d reviewed it sooner. That way I’d already have had more of it. More dice. More tiles. More rolling. More of the black hole bag. More. More. You’ll never cure me. Never.

Phew. I got through that whole review without mentioning those god-awful dice cups. Those things are like beakers for babies.

An addendum: Do I like this more than Race for the Galaxy, one of our and my most favourite games? Sort of! I’ve played Race a lot, really an awful lot, so my bias here comes both from Roll being new and fresh and Race being maybe too familiar. This feels like the old theme using new mechanics, which is a pretty impressive thing to do, and it naturally presses a few of my personal buttons. I also found it easier to pick up than Race, which warmed me to it much faster. Really, though, I’d need to play Roll many, many more times to properly answer that question.

I guess I’d better get on that and I very much look forward to it.