Brendan: Out of Dodge is a game that understands one of the golden rules of the criminal genre: a botched heist is a good heist. As four outlaws on the run from a job that went terribly wrong, there is room here for hi-jinks, comedy, seriousness and treachery. It is a short, one-shot RPG from Jason Morningstar of Fiasco fame and it has a dastardly fun set up: you arrange four seats in the shape of a car (or use an actual real-life moving car), get in and argue about what went wrong while you speed away from the crime scene with a bag of loot much lighter than you expected.

Oh yeah, and watch out for all the blood because one of you is dying.

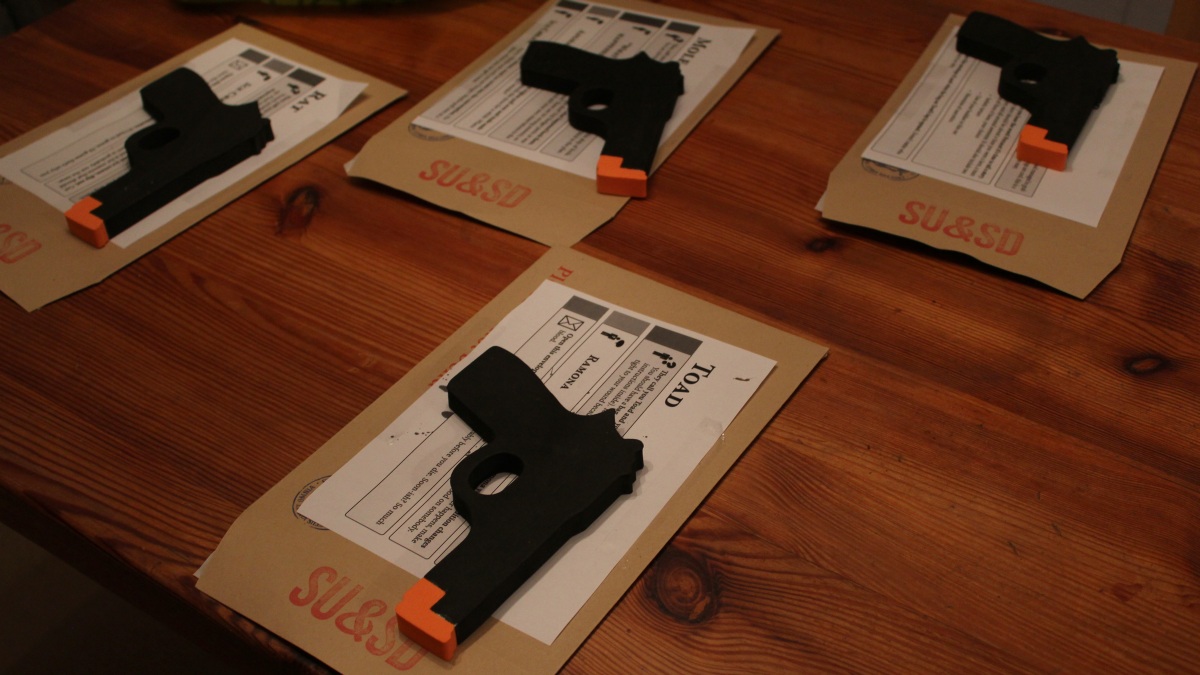

It is also a heavily tailored game. I’ll try to keep spoilers to a minimum but if you like your role-play as fresh as a carrot (???) then your best option is to read this article and nothing more. Here’s how it works. You print out four character pages, each with the name of their respective crim and a short description of their personality. As with all good heists, it looks like you’ve been using code names. Toad, Mole, Rat and Badger.

Each player gets an envelope with their character on the outside and another sheet inside with some extra information that will come into play later. Mole, the driver, is calm and in control. Badger is an experienced, cheerful old robber. Rat is angry and ill-tempered. Toad is bullet-riddled and (unsurprisingly) a little cranky. Players aren’t to know all the details on their fellow fugitives’ sheets, however. There are aspects of everyone’s personality, as well as certain story beats, that are triggered by prompts and keywords. While this hidden information makes the game difficult to prep as the host player (don’t look don’t look don’t look) it also prevents the dialogue being ruined by knowing too much about everyone’s motives. The only thing that is clear to everyone is that Toad is dying. He has been shot and nobody seems to know how or why. The paranoia is afoot.

You also randomly place one of six possible notes into the loot bag, with eleven pieces of precious something. These can be coins, tokens or whatevs (we went with a bag of ancient jewellery, custom-made from chocolate coins and gold-coloured picture hooks). The note inside (pre-written by the game’s designers) is to be read by the person who first cracks under the pressure and opens up the booty. The details written here are pretty much the catalyst for the game’s climax, so how long your game lasts will likely depend how quickly you burn through the shouting and blame-wavering of the early parts. You will also notice that eleven doesn’t split four ways. Or three ways. Or two ways, come to think of it. At the start of the game, Toad is clutching the bag. This is likely to change. On top of this, everyone has a gun. We used the foam firearms of Cash ‘n’ Guns for ADDED REALISM but there is no reason y’all can’t just point your fingers at someone, playground style. At any point one of you may die, but in this case the game instructs you simply to stay quiet for a few minutes, then begin making provocative comments and snide remarks “from beyond the grave”. The game ends, like a lot of role-play, whenever it feels like it should. Maybe you all work through your differences and drive off with the loot split between you as fairly as you can manage. Or maybe you all die in a bloody shoot-out and crash the car into an oncoming 18-wheeler, exploding like an angry barrel of propane.

Like I say, it’s hard to talk about the fun parts of our game in any detail without spoiling some of the designers’ scripted silliness. The whole idea of the game is for the four of you to piece together the story of the heist. Where did it take place? What was the security like? What each of you did during the action? How the hell did Toad get shot to bits? The keywords mechanic is sort of a lubricant here. One of you might be prompted by your sheet to work the word “Ice Cream” into the conversation, while another is instructed to react violently to any mention of that word. On the one hand, this means you only really get one go at all this before you know how it all works. On the other, I can easily see every individual playthrough going differently for each group. Even though it includes a “form” version, allowing you to change the keywords, it is still sort of a one-night stand of an RPG. Fun, frivolous and, er, short.

With our game, we set up our four seats in front of a TV screen with this video playing for added carfeel. And although “carfeel” is a word I just invented, it really worked. Well, sometimes. The moment in the video when we stopped to let a train pass led to a great bout of bickering (“Why have we stopped!” “Do you want me to drive into a moving train?” “Can’t you go around!?” “Have you seen how long this is!” “OH GOD SHUT UP.”) but it also prevented us from “pulling over” because the dashcam would have clashed with whatever was going on in our heads. A weird cognitive hiccup. I’d recommend going without a video simply because it gives everyone more control over what’s happening. Maybe you pull over into a 7-Eleven for some ice cream.

I don’t think it’s for everyone. There’s a structure to it that can’t be shifted or altered and will probably alienate folks who want a more open-ended scenario. It is also strictly set to four players, which is a bummer. Our game also lasted just twenty minutes (not the hour the rules seems to think it is due). But honestly, any longer and it would have felt overdrawn. Brevity is best and for anyone happy enough to ad-lib their way through the script, it offers some super punchy moments. It’s a sketch, rather than an episode. Or — FOOD ANALOGY — something you can bite into and digest speedily, ready for something sweeter and more filling to follow, like ice cream. Anybody want to stop for ice cream?

Pip: STOP. TALKING. ABOUT. ICE CREAM.

[BANG]

Pip: Out of Dodge. SU&SD recommends.