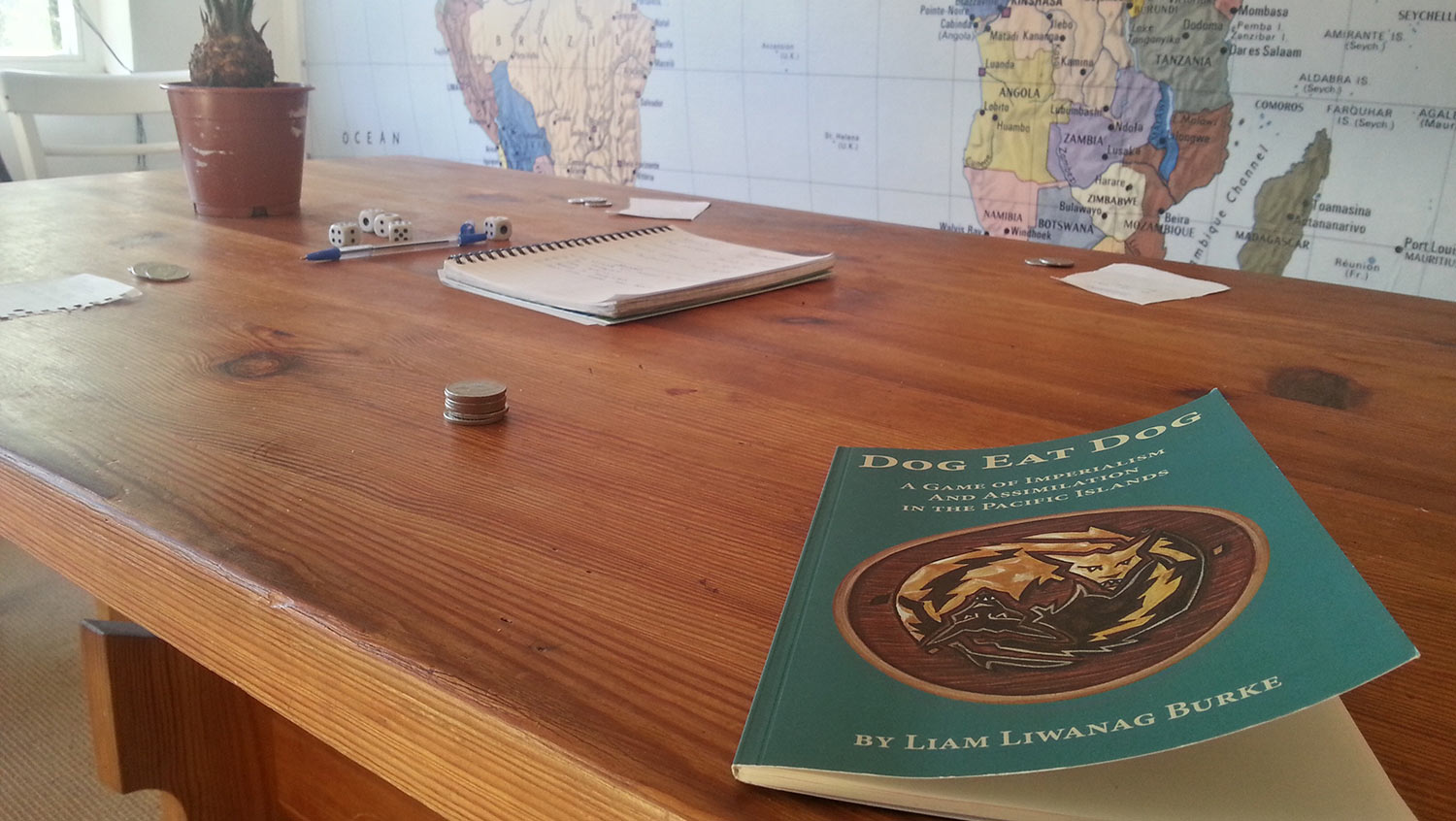

Brendan: Dog Eat Dog is one of those rare games we come across that do not necessarily have ‘fun’ as the end goal but, like Freedom: The Underground Railroad, try to impart some wisdom on their way through your life. It is thoughtful and intelligent and just a little uncomfortable. It’s a game with a point to make and it makes it worryingly well. If I were to describe it using SUSD’s internal style guide, “Rulez, Regulationz and Ztuff” I would call it an indie RPG about the colonisation of an island and the resultant back ‘n’ forth between ‘native’ and ‘occupier’. But since I already burned my style guide when it suggested I use ‘paragraphz’, I will have to settle for this description:

Dog Eat Dog should be taught in schools.

It works like this. Your group sits down and decides, firstly, where you will set your colonisation tale. In one game we set it on the island of Avarua in the late 1700s. It is a place and time we may have known little about but we still managed (I think) to create a story that is true to the spirit of the game. An earlier game saw us setting it on a distant planet, peopled with small, aquatic natives and visited by the hard-skinned, heavily smoking citizens of another world. (Personally, I imagined these occupiers as Krogans from the Mass Effect video games with Marlboro Lights in their big jaws, but that may have just been me.) As different as these settings were, both games felt true to me as far as the message of the game goes. And that is down to the impeccably smart design of the ‘game’ itself.

One person will act as the colonising forces – all of them – while all other players are individual natives (or can stand in as ‘NPC’ natives). Everyone takes turns coming up with a descriptor for both parties. “I think the natives are… prodigious weavers!” or “Maybe the colonisers are, like, super tall!” Once the characteristics of the both sides are decided, you need to decide who among you will play the colonising forces. That’s when you get to drop this question on your friends, this absolute brute.

“Okay, who here is the richest person?”

That’s right, the richest player at the table is the coloniser. This is DED’s first masterstroke of discomfort – a stuttering bombshell from the most socially awkward B-52. The game does not go into anymore detail. It does not give you any definition of what ‘richest’ is, which leads to a lot of muttering, guffaws, uncomfortable disclosures, raised eyebrows and general embarrassment. Eventually, it is somehow decided that one person is richer than the others. In class-obsessed England, where it is just plain rude to talk about income, expenditure, debt and property ownership (haha, property ownership), this is as about appealing as sticking a barbeque skewer in your ear. But press on, please, press on. Because this game is going to teach you things.

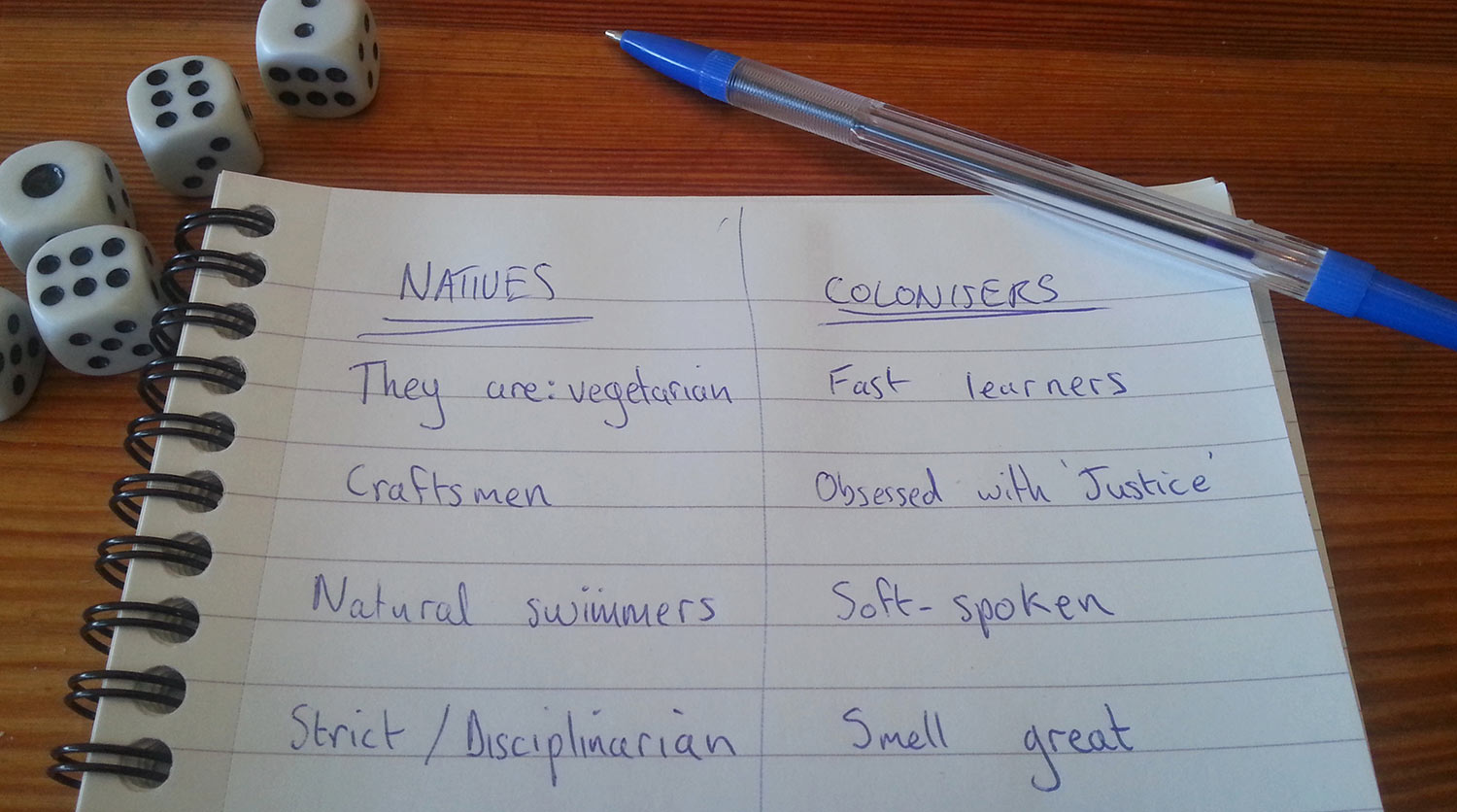

Next, each native player comes up with a descriptor for their own character, something that makes them stand out in their homeland. (“I am the most successful fisherman!”, “Well, I weave the best baskets.”) So at the end of the set up you will have a piece of paper that looks like this:

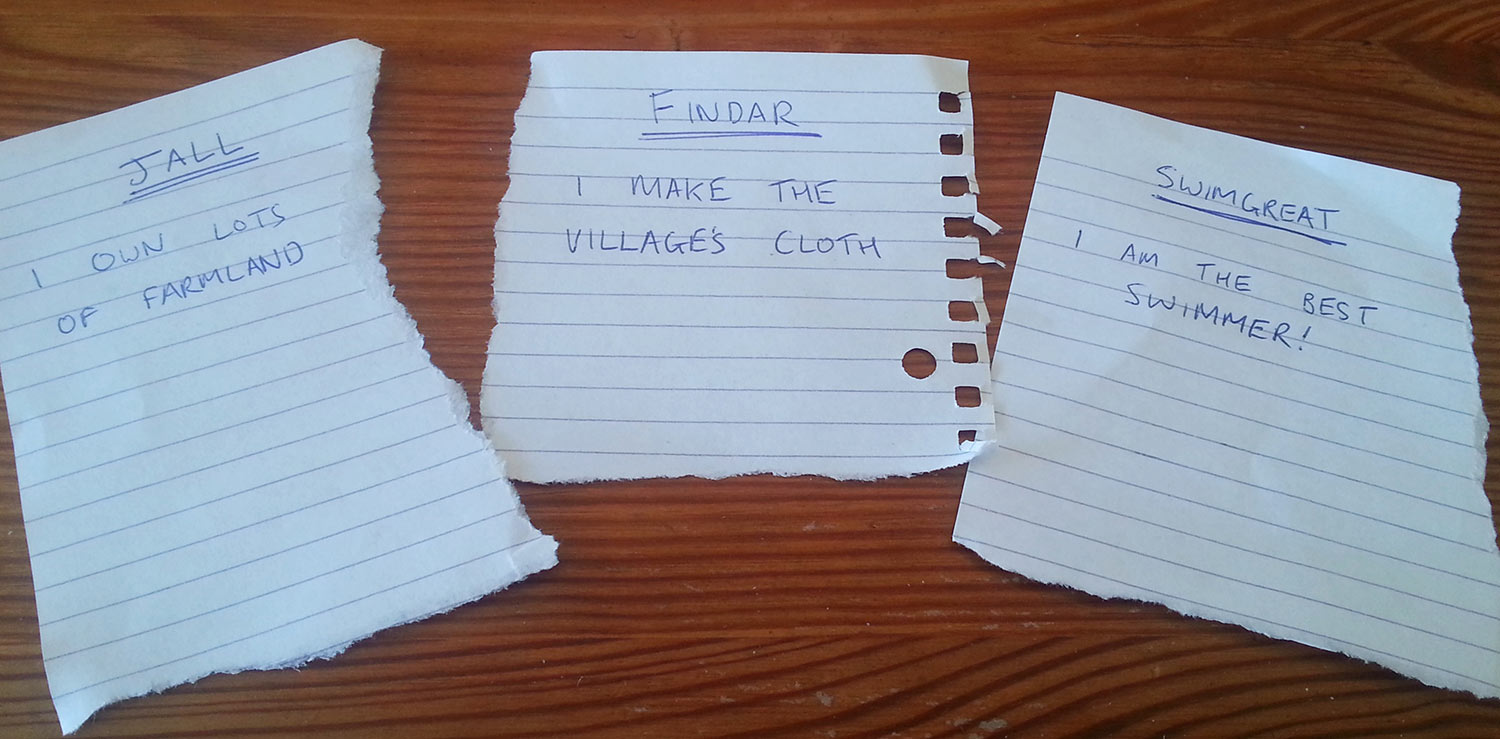

And some pieces of paper around the table, for each native person, like this:

You’re nearly there. Next, you’re going to need some tokens. Go get some tokens! Give each native as many tokens as there are players. Then, give the coloniser twice that number and an extra token for good measure. Do you see where this is going? We used coins as tokens for our games, which only emphasised the whole set-up. The richest person at the table really had more money in front of them.

Soon you will be taking turns setting up scenes, starting with the native to the left of the coloniser. During these enactments, the scene-setting native can invite other natives in and generally decides on what is Going On. Maybe you are all throwing a party for the youngest member of the village? Maybe you are coming home from a hard day at sea? Whatever it is, the native players will be there, doing whatever it is your natives are deemed to do.

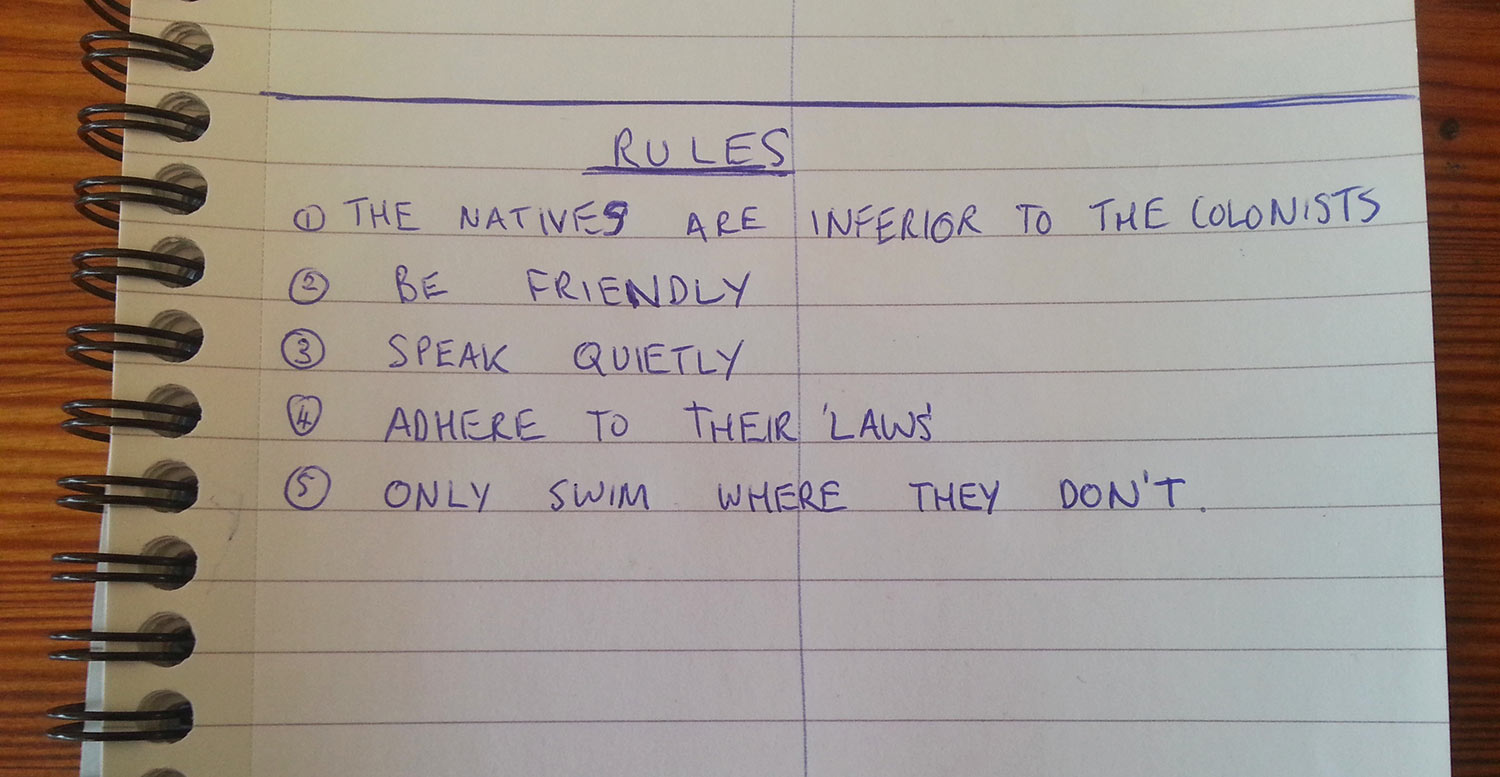

Unfortunately (and somewhat fittingly) the colonising forces can enter a scene whenever they want. In fact, the game encourages it — but more on this soon. There is just one last thing to mention before we get onto that. There needs to be rules. What kind of colony does not have any rules? They will be added as the game goes on but, for now, you only start with one. However, it must always be this rule. I suggest writing it in print, like so…

THE NATIVES ARE INFERIOR TO THE COLONISTS.

Here is Dog eat Dog’s second bombshell. Any time a rule is broken during a scene, the colonising player can take a token from the offending player(s). Any time a rule is obeyed, the coloniser must give the obedient player(s) a token. At all times, the natives must at least act “inferior” if they want to keep their tokens. What happens if they run out tokens? Well, it gets a little complicated in terms of scene-setting but essentially they will die in some horrible way.

Terrible things will now occur. The colonising player is encouraged by the “money-grabbing system” to invade the native’s scenes and engineer conflict, hostility and ill will. The native players will not want to stand up to the coloniser too openly, or too often because for each rule broken they come closer to a terrible, violent death. At the end of each scene, the natives must come up with a new rule, based on the ‘moral’ of the last scene. For instance, one scene in our game saw the coloniser (me) badgering an elder of the natives to take the Christian God into his settlement’s life. After that, Pip and Quinns came up with the rule: “ACCEPT GOD”. A separate scene saw our alien occupiers becoming annoyed when the aquatic people would not trade with them. The rule “FACILITATE TRADE” was quickly established.

For me, this is the game’s final ingenious ploy. The natives wrap themselves up in rules, with no input from the coloniser. But it is the coloniser who decides whether or not they broke the rules. From that point it is simply a matter of employing the rules to get the natives to do what you like. In the game of the aquatic peoples, I learned this lesson the scary way. My character, Grub the shoemaker, was packing his kelp rucksack and getting ready to escape his occupied homelands for a hidden underwater trench. “Don’t worry,” I told my niece, “I will be back next year to perform the Landwalk ceremony.” But the colonisers had other plans.

“Grub,” said Coloniser Quinns. “Your phone is ringing.”

(We had an underwater communications system)

I hung up and continued to pack.

“Your phone rings again.”

I turned my phone off, buried it under some stuff. I told my niece she should go back home to her parents and I will see her when —

“Your niece’s phone is ringing.”

I grabbed it from my niece before she could talk and heard the voice of a coloniser. He hoped I wasn’t going anywhere. I tried to tell him I was just going to the trench for some short-term research.

“I hope you’re not lying to me, Mr Grub.”

I looked down at the list of rules.

DO NOT LIE TO THEM.

“Well,” I said, “short-term, I mean, you know, one year should do it.”

“I’m afraid we would like community leaders like yourself to stay.”

I looked at the rest of the rules on the page. I looked at my pitiful trio of coins. One act of defiance would probably clean me. I thought of my niece and I told the Krogan on the phone that, no, in hindsight, it wasn’t necessary for me to go anywhere. I could do some research here.

And that was it. I capitulated.

Dog Eat Dog offers a lot of these slow, painful conversations. Some are more subtle than others and some are more violent. But always the message is clear: the colonisers are the ones with the power. There is, like a lot of RPGs, a ‘conflict’ system which involves rolling dice to see who is correct about some version of events — coloniser or native. Coloniser lost the roll? No they didn’t. Forget what number you saw. The rule book is clear. The coloniser ALWAYS has the power to dictate what happens next. It is a game that furnishes you with a deeply unfair world and asks you to live in it as best you can.

Okay. Let me take a break to tell you some things. I grew up in Northern Ireland, a place that still resonates, ever-so-slightly, with the effects of — let’s call it what it was — imperialism. In terms of colonialism, the Irish experience is a very, very old one. Ireland has undergone a slow-burning colonialism, unlike the rapid, industrialised colonisation of the Americas, or the grotesque racial “adventures” that took place across Africa, both much worse to me in terms of the atrocities that took place. But ours has been a colonialism effective enough for me to often look at myself and wonder: what am I? I do not feel English and when people ask me where I’m from, I say I am Irish. But the sad truth is that I am closer to being an Englishman than any generation of Irish people was before. I speak English to everyone I know. I work for a British newspaper and two British-American websites. I live in London, for heaven’s sake, the home of the bloody awful Queen. I say things like “bloody awful”.

Perhaps this is why it was a little cathartic to play as coloniser against two British people. Make no mistake, in my second game with only Quinns and Pip, I did not pull any punches. My colonists beat natives who refused to work, they threatened them with death and disappeared people as examples. My soldiers I described as being “dressed strangely”. In my mind, they were wearing red coats.

I am not a patriot, nor a nationalist. I dislike the idea of the country, the super-tribe, even if I concede it is a thing which must exist. But there is something deep in me, like so many Irish people, that resents imperialism in general and British imperialism in particular. It is a history that has been largely addressed and the political wreckage of that history is not the worst among the nations of the world. But it is the history that has affected me.

During my in-character colonist brutality I sourced many things from what I had read or watched recently. The work enforced on the natives (picking flowers) was straight out of Twelve Years a Slave, which I watched, painfully, on the plane to GenCon. The presence of an islander who translated for the occupiers and fancied himself a Superior of his fellow natives was the ahistorical counterpart of Chaim Rumkowski as described in Primo Levi’s Moment’s of Reprieve. (“It’s the translator I hate,” said a deathbound Quinns, sizing up who to attack with his final action as a free man).

But tellingly, I also plundered images from my country’s collective memory (read: Our Big Book of Propaganda). There was an execution scene to match the aftermath of the Easter Rising (sorry, Quinns) and, most importantly, the invading soldiers were unmistakably the squaddies of my own dad’s stories of growing up in 1970s Belfast.

There is one way in Dog Eat Dog for the natives to coerce the colonisers from their island. But it is not open rebellion. By obeying the rules that are set and deferring time and time again to the increasingly difficult rule of the occupying force, you may eventually gain all tokens from the colonist. At this point the manual says that the colonisers must leave peacefully, that the natives have ‘won their independence’. But at what cost? This is just another lesson the game teaches. Even when the colonisers ‘lose’ the natives do not really ‘win’. Just look at the list of rules they have been left with, rules which they themselves felt forced into creating. The islanders have lost their dignity, their history and their identity. Here is the true impact of the game for me. Not what it allows me to do, in mock justice, to my British friends (as if the sensitive soul of Pip needed telling!) but what the game shows me of the defeated people. Those who have lost something intangible. Now, ‘intangible’ is a wanky word, used by wanky people. But that’s what an assimilated people lose, something intangible. Something they can no longer know.

I have, on two occasions, been so disappointed in myself for not holding onto my Irish heritage that I nearly cried.

The first time:

I was sitting in my friend’s house in Derry, after visiting home. He spoke fluent Irish, his girlfriend spoke fluent Irish. Even their daughter spoke fluent Irish, or rather, she spoke it as fluently as a three-year-old can speak anything. My other friends sat around talking, in English, but when the little girl would wobble over and seek an audience with any of us grown-ups, they would reply to her only in Irish. They were bringing her up with the Irish tongue first, and the English tongue second. And since I could not speak Irish well enough, I couldn’t talk with her. She would just look at me, confused. I looked at my friends, the parents, and thought: “If I ever have a child, I will not be able to do what they do.” I had forgotten my language — ‘our’ language. I cannot communicate to you now how low this made me feel, how low even reminiscing about it now makes me feel. I sat in the armchair of my friend’s living room and smiled and felt awful. Inside the hollow of my mind there reverberated a single sentence, half-epiphany, half-curse: I have abandoned my people. It was one of those moments when you remember thinking each word in turn, so clearly it may as well have been written across the walls. I have abandoned my people.

The second time I was so disappointed in myself for not holding onto my Irish heritage that I nearly cried:

I lay in bed after the first night I played Dog Eat Dog and thought about it.

Pip: In our first attempt at Dog Eat Dog our band of natives ended up in a weird televised stand-off with a merchant from outer space who wanted to own our undersea garden and start some kind of workplace traineeship. It wasn’t exactly the uncomfortable colonialisation experience we’d been expecting. The second game… By the end of the second game I was nearly in tears and Brendan seemed genuinely concerned about the state of our friendship.

You can read more about how the game works in Brendy’s account – I won’t repeat it here because he explains it well – but I thought I’d add a few of my own observations and experiences.

I guess the first is how uncomfortable it is to even come up with the starting scenario. I don’t share Brendan’s experiences nor the heritage that comes as a result of being the oppressed people. I’m white and middle class and British. I’m also very much aware the effect white British society has frequently had on vast swathes of the globe.

My discomfort was largely the discomfort of the historically privileged. What I mean is this: colonialism has distorted or destroyed cultures, it has ruined lives, it has taken away power and representation from so many people. In playing as a native I worried about the fact I was essentially speaking with someone else’s voice – I worried I might say something utterly ignorant or patronising or jocular. (I also worried about being that hand-wringing idiot.)

That’s why I’d been the one suggesting a futuristic setting the first time round. I thought it would let us play with the game and its themes without accidentally trivialising real history. For a number of reasons it didn’t work and we went with a sort of 18th century Pacific island setting for game two.

The rule we’d been most lax on in the first game was the most important. In fact, it’s the only rule the game gives for your list – natives must be inferior to colonisers. The chain-smoking space merchants of our first attempt were less of a superior occupying force and more of a browbeaten corporation. The engagements frequently began on a more or less equal footing and we tended to assess success in sticking to the inferiority rule by the condition “well, they definitely weren’t superior“.

Brendan embraced the inferiority rule and would deliver all these little verbal reminders either to goad you towards breaking a rule or just to reinforce the power dynamic. The guards holding you would jab you in the ribs while you struggled to formulate an answer. A villager being bullied by a gun-wielding coloniser was stripped, then berated by the colonisers for being naked in the sight of God, then disappeared. Fairness seemed to permeate both sides in our first game. In the second it was almost entirely absent. The native were simply inferior.

The inferiority rule is the lynchpin of the game, which brings me to something I’ve been turning over in my mind from time to time since we played. The game is called Dog Eat Dog. It’s a phrase which denotes an environment so hostile or cut-throat that you will screw over the rest of your species in order to advance. It’s horribly apt for the game. The title reminds you of a fundamental equality in humanity then slams you with that rule. Yep, they are your fellow man but they happen to be from a different land and you have fire sticks so go play…

We gradually built other rules around that first one to try and keep us safe from the colonisers. To try to find ways to make them leave. It culminated in this final scene:

My character, Pop, goes over to the colonist translator to hand in a basket of flowers she has been ordered to gather.

“You need twice as many twice as fast – these men will not settle for this,” he tells me.

I pick up the basket and return to a clearing, working as fast as possible before returning a heaving basket for inspection.

The translator calls a guard over who slaps the basket out of my hands, spilling flowers everywhere.

“Pick it up and start again.”

I do exactly that, reaching for as many of the spilled flowers as possible. When the basket is so full I can barely lift it I return to the translator.

“I think there’s definitely room in there for more – don’t you think so?”

Brendan needs me to break the rules in order to “win” the game. (spoiler: nobody ever really wins in Dog Eat Dog) Anything other than my agreement will be taken as insubordination and I will have broken that first rule. As a result he’s constantly pushing, trying to prod me into a retort.

“Fill two baskets”

By this point I’ve resorted to balancing flowers on top of the full basket. I refuse to make eye contact with Brendan. There are no right answers, only traps.

“Occasionally I’m looking at my fellow villagers’ baskets to make sure they’re doing their work,” I say as I narrate the scene. I’ve tipped over into active inferiority at this point. I want Brendan gone from the game and the only way to achieve that is to be aggressively obedient to all the rules we’ve defined as we played.

Brendan pauses.

“Okay, some of the guards go over and start kicking some people.”

“OH, COME ON!” Quinns calls from the other side of the living room table.

“That will be you if you don’t fill these baskets faster” says the translator.

I come over with three full baskets and am accused of insolence. I tell Brendan we’re out of baskets. Surely that’s an acceptable way to end this back and forth without breaching my inferiority? I played the audio back and one of us is actually tapping our pencil on the table at this point, stressed out by the scene.

Brendan reacts by having the translator send two soldiers off and they return with a basket. They hand it over, smiling.

“Why don’t you put some in that. It might be a little heavy. I think there’s something in it already…”

That’s when I was done. Utterly done. I knew whatever was in the basket would be repulsive. I was stuck somewhere between the brutality remembered from Lloyd Jones’ Pacific island-based book, Mister Pip, and that horrible box in Se7en. We went through the rules to work out who had obeyed what and how to divvy up the game tokens. In the end all we had done was maintain the status quo, except now Brendan felt sick and I thought I might actually start to cry.

It’s such a good game. I’m still thinking about and being unsettled by it a week later.

In fact, I’d say it’s probably the best game I never want to play again.

[Dog Eat Dog is available direct from author Liam Burke here.]