(Images courtesy of BoardGameGeek.)

Thrower: General Patton chewed his cigar and look East, over the Rhine, into Germany. He’d done it. By loading his divisions down with fuel, he’d stolen a coup on the other Allied commanders and made it to the river first.

Now, only the 155th Panzer Brigade stood between him and the history books. Disorganised and demoralised, they were no match for his crack US corps.

Suddenly the field telephone crackled into life. “Sir? Sir! We can’t action that advance order. The troops have no ammunition. Montgomery requisitioned the lot.”

“WHAT?” bellowed Patton, spraying out a mouthful of cheesy wotsits. “That British f*** took EVERYTHING? Jesus!”

Monty put down his beer, and waved across the table with a cheery grin. Bradly, meanwhile, bribed Axis troops to cut Patton’s overextended supply lines, leaving him stranded without food, or hope.

Welcome to Race to the Rhine, a German-style game in Wargame’s clothing. The rules are easy and it’s quick-playing. There’s little randomness and lots of wood. Yet it drops mortar bombs on the concept of play balance, and smacks a sniper round into low interaction’s forehead.

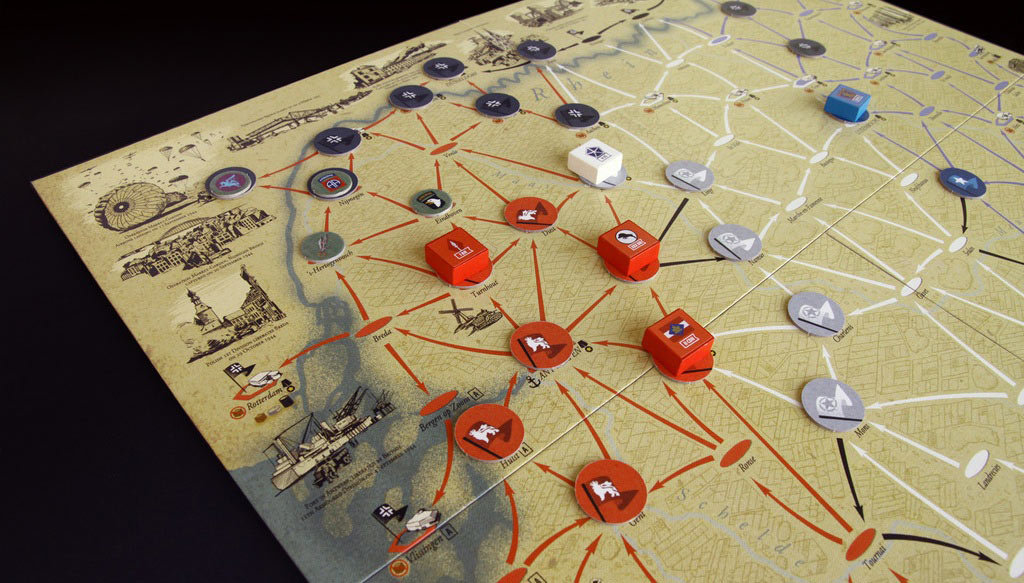

Military history offers few scenarios that lend themselves to three players and low chance. But this game has found one. In the dying months of World War 2, the three generals in Allied high command were vying to be the first to cross the Rhine into Germany. Their opposition was chaotic and demoralised. The Allies were almost guaranteed to win battles, so long as they were properly supplied.

So that’s the game. Keep your divisions in supply and your flanks protected and see who’s first into Germany. It sounds dull but it’s fiendishly hard because you chew through those supplies as you advance. You’ll burn fuel to move, ammunition to bypass enemy units and food based on an in-game timer.

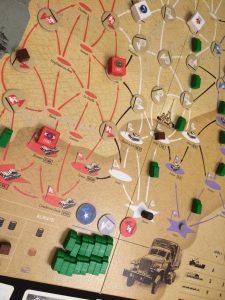

These critical resources run low with terrifying speed, so you stick trucks down on the board to represent the famous red ball express. Each one allows you to shift a cache of supplies between adjacent areas. Gradually, stuff moves up from your depot to your front lines.

But once you’ve used a route, it’s jammed with traffic. The next consignment will need to find a different way forward. Then you’ll need to requisition some more trucks from a limited pool, if your greedy fellow generals haven’t snaffled the lot already.

Everyone’s competing for the same resources, see, and there’s not a lot of if about. There’s still a war going on in the Pacific, after all. If you’re the only general with fuel then by god, you’re going to want to stockpile all the rest just to make sure it stays that way. But that’s going to cost you one of just two actions you get each turn, while the time limit ticks inexorably downward.

Same with the trucks, except the pool is even smaller, and you can decide how many to leave. So it’s sometimes left with just one truck to take. And by “sometimes” I mean “always”. Because then, someone has to waste a whole action to get one wretched truck, while their opponents sit by, smug with their fat transport pools.

It’s a wonder any of these jerks ever made it across the river at all.

If you’re struggling to manage it, you have the useful option of stopping the timer. It functions from a limited pool of Axis markers, which players place on the board at the end of their turn. Land on one and instead of drawing a benign card from your own deck, you pull from the Axis cards instead, full of famous, fearsome historical units. You better have lots of fuel and ammo before braving one.

Instead of placing a marker you can choose to counterattack and remove one of your opponent’s markers instead. That makes the game longer, but can also disrupt their supply lines, leaving units stranded. It pays to co-ordinate your units to protect your flanks. Yet your flanks aren’t yours to protect. Each general advances up their own parallel route toward the Rhine, and a mean player might leave their allies exposed. The inevitable result is three thin prongs snaking up the map with vast gulfs between.

What this all adds up to is a glorious, overwhelming mess of moving parts that you must somehow make sense of to succeed. Trying to track all the permutations can leave you feeling like an entire armoured division has driven over your brain. So you give up, guess, and the game lurches forward at a reasonable pace. Right up until the bastard on your left captures the city in front of you, and your division burns precious, precious fuel and time as it backs up, cursing, to try another route.

Sometimes, it’s too much trying to keep so many plates in the air. Especially when all the players are trying to do their best to saw through each other’s poles. It’s a difficult, frustrating game, teetering on the precipice between challenging fun and hard work. But trying to keep all those cogs spinning together takes a lot of mastery, and that ensures vast replayability.

As if that were not enough to sustain interest, the game is asymmetric. Each of the three generals has a different deck, a different section of the board and a different special power. Monty is rolling in supplies and units but faces the toughest challenge from German units. Bradley has the longest supply lines, but better logistics to sustain them. Patton has no weaknesses, except that both other players know this and will ensure his game is ninety minutes of living hell, every single time.

Games with multiple asymmetric positions tend to work best with a full complement, and Race to the Rhine is no exception. The solo variant is worthless. The two player game is fun, but flawed. With all three, this is a unique experience, and game that makes logistics not only exciting but viciously cut-throat.

For all its brilliance, flavour and clever historical premise, it’s not really a wargame. Its realistic roots are fundamentally flawed. For all their desire to be the first to the finish, the real commanders would never have engaged in playground squabbles like they do here. They had a war to win and lives to save.

Does that matter? Hell, no. I can see myself playing this long after my paper maps have torn and my cardboard corps have frayed. It’ll still be hitting the table when I no longer have the mental capacity to digest 40-page rulebooks. It may not be a wargame, but it’s one of the few Eurogames that lives up to the brutal, heavy image they project for themselves. And for that, it’s a keeper.