Matt: I don’t know if this is by far the silliest thing we’ve ever reviewed…

Paul: …and I don’t even know if that matters or not. Is PitchCar silly? Is it also possibly the simplest game to ever grace our (web)pages? Is it even a board game?

Matt: Do we even care?

Paul: Will we ever stop using the word “even”?

Matt: PitchCar is a very big game, a sprawling game, that’s all about racing (and not to be confused with PitchCar Mini, which is a slightly smaller very big game that’s all about racing). It’s so large that, unless you own the sort of grand dining room table seen in the glossy aspirational photos dotted throughout this silly review, you’ll be stuck on the carpet roaming around on all fours like a gaggle of sugar-riddled toddlers. We sadly don’t own this kind of table, but thankfully are well-accustomed to the latter.

It’s like an alternate reality version of Snooker crossed with Subbuteo, and set on a race track. That’s a terrible description, but the mental imagery is wild enough for me to justifiably try and keep that line in. It’s pretty tough, can get very competitive very quickly, and has almost no rules at all. Most importantly though, it’s tremendous fun.

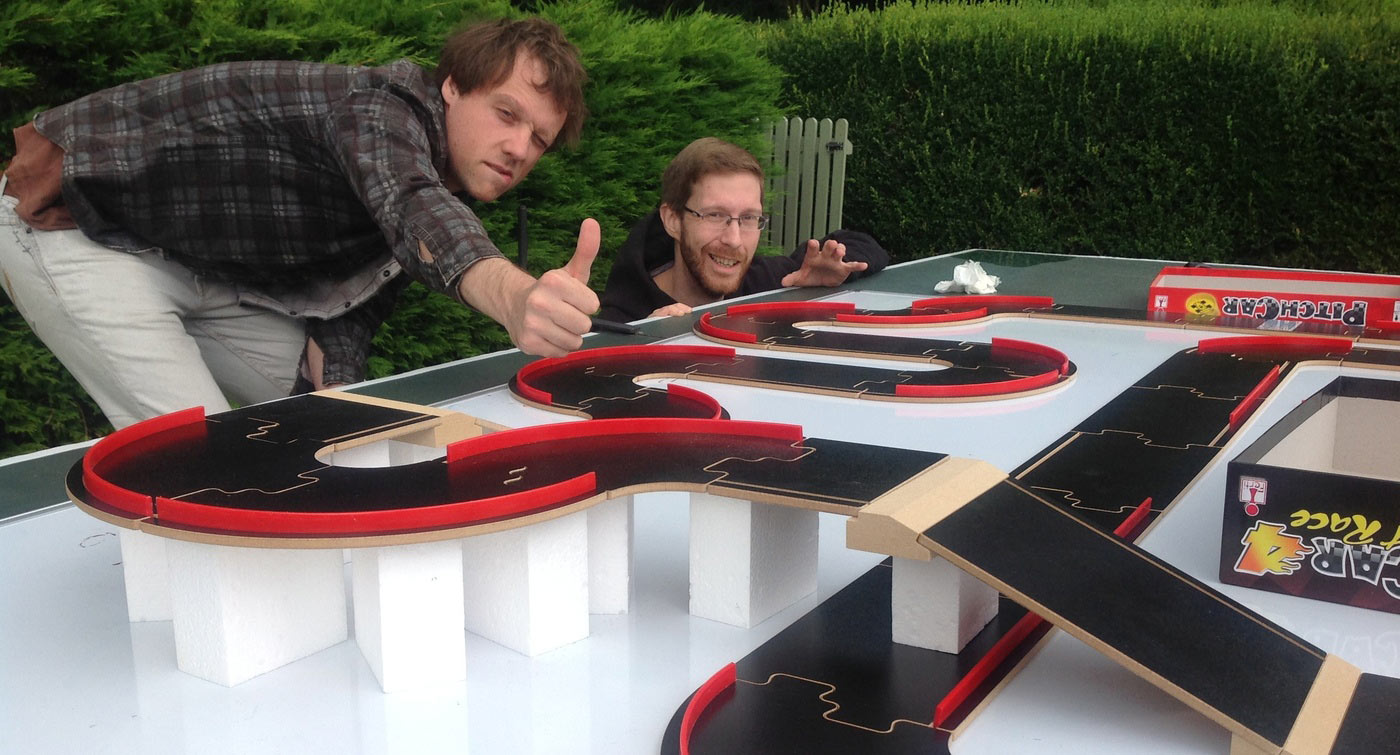

Paul: Yes! PitchCar is mostly ridiculous, so ridiculous that you’re expected to use the styrofoam that comes in the box to build bridges. It’s a game of flicking small wooden discs around a flat wooden race track. As I’m sure you’ve guessed, the discs represent race cars, while the track can be assembled just like Scalextric, corners and straights clicking together with Legolike ease. Naturally, this means course designers can create track after track after track, making them as complicated or as cruel as they fancy.

And then you race on them. You race by carefully lining up your wooden disc cars and then just taking turns to flick away. Flicking down the track. Flicking hard to shoot down straights and flicking gently to take difficult corners, hating your past self for placing a wall there and not there (“What was I thinking?!). You flick, flick, flick away and that’s just about it. All you need to do is flick better than anyone else, so that you can cross the finish line first. That, if you didn’t know, is how you win a race.

Matt: There’s a bit of nuance here and there, too. If your overenthusiastic flick sends you flying off the track, which is something that’s going to happen all the time, you have to put yourself back where you started. If you knock someone else off you’re supposed to go back too, although we much preferred the variant where knocking someone else off the board put their piece back to where you flicked from. This aggressive optional rule doesn’t impact things too much, and mostly people will want to play it safe, but does make the game even more reminiscent of Codemaster’s Micro Machines, which is obviously rad. Bagsy being Spider.

Thankfully the game can be made far less nasty by the special red plastic track barriers that you can bounce off or even use to swoop around corners, providing you make the shot you need to perfectly which you almost definitely won’t. Where you put these barriers is almost entirely up to you, once again splitting the world into two distinct warring groups: Those who believe ten-pin bowling is more fun with bumpers, and those who believe that those people should be exiled to live outside of the walls and forage for themselves in the radiated wasteland.

Paul: You see, PitchCar is hard. It’s really hard. It turns out that human beings are not great at flicking things around and, while millions of years of evolution have made our bodies very good for walking or twerking or providing reliable, trustworthy and on-message financial management services, they’ve left us useless when it comes to helping tiny tokens slide around a chicane. There’s a physical comedy in even trying and doing it wrong over and over is part of what made Catacombs so much fun.

Matt: That’s if you’ve even made a relatively straightforward track and you’re gently, carefully flicking your way forward. If your track is the invention of a drunken draughtsman or someone using a spirograph in an earthquake, you’ll be crashing every other turn. If your players are even a little bit aggressive, you’ll be crashing constantly. But that’s the point.

PitchCar isn’t going to be your type of game if you’re after something that’s built upon a system of complex and cleverly constructed rules, or if you want to show off your intelligence, or if you want to feel like you thoroughly outwitted everyone else. It’s far too silly for that but, if we’re honest, we’re pretty silly people ourselves and we don’t mind flicking things about for fun and rolling around on carpets laughing.

Having said that, it isn’t a game just about finger-prowess. Anyone who’s spent time playing Pool will appreciate the value of psyching people out, and an element of PitchCar is all about mind games. I didn’t mention that to Paul and Quinns at the time because I’m a genuinely evil person, but what you want to do is either hover behind them like a weird vulture or stand directly opposite them, in the direction where they’re going to take the shot. If that sounds fun, this game is for you.

Paul: Last weekend, Quinns and I built a track that had a bridge in it, because you can also get ramps and support blocks to build raised tracks. Are these any easier to navigate? No! Of course not. What they are is even more fun to build and even more chaotic. Do you know how much further someone else’s wooden disc can go when you ram it off a bridge? Considerably further! Much further!

And that’s the point, that’s what PitchCar is all about. It’s friends getting together to be silly, to race, to play. It’s a game for kids who are big or not so big and it’s also a game where making the track is half the fun.

Matt: I think that’s a really valuable point to focus on, actually. As a child I spent a ton of time with my brother trying to make increasingly audacious Scalextric tracks with my brother, using beanbags as loose support for wonky tracks that had vertical sections where the cars would temporarily drive up the wall before turning a chicane and returning to the ground again. That process of collaboratively building a challenge and beating it together sort of transcends the competition. But most importantly of all: I won. I’m the best, I’m the best, you guys are rubbish, nerr nerrr nerrrr