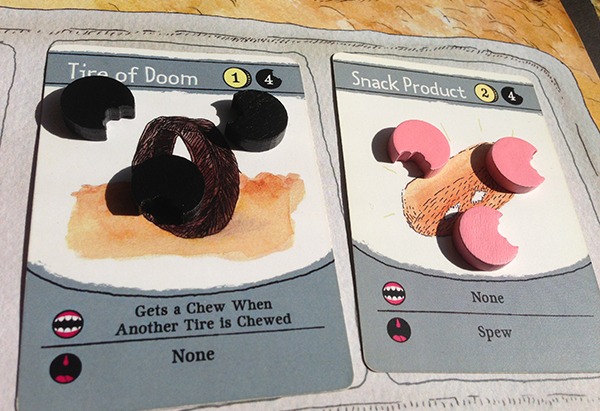

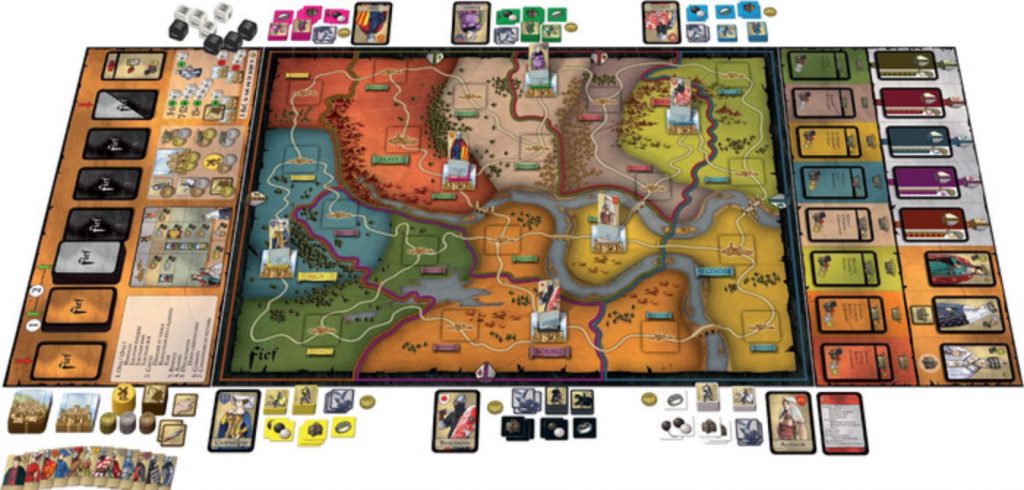

[Zach Gage is a New York-based game designer, artist and friend of SU&SD whose work recently saw a change in direction. After success in the App store with SpellTower and such high-profile experiments as a videogame that penalises failure by deleting files on your computer, he’s started working with table games. Guts of Glory is his post-apocalyptic eating contest, and is arriving very, very soon. We got in touch to find out where the shift came from.]

Quinns: Can you explain how the New York University Game Centre came to commission Guts of Glory?

Zach Gage: Sure thing!

Actually I think they wanted me to make a weird artsy game. They commission a few people each year, and typically, one of those people is the type of person who sometimes makes really odd games. Robin Arnott and Terry Cavanagh filled this roll in years past. I think Charles was expecting something closer to Lose/Lose or Killing Spree from me, the card game came a bit out of left field.

When Charles first offered me the commission, one thing that he said that really stuck with me was that the reason the commission is paid, is to give game makers the chance to do something they wouldn’t normally do. I think this typically means make a weird game, but in my case, SpellTower had just blown up and the commission money, while important to me, didn’t —for once— have to go right into groceries and rent. I spent a long time thinking about how to do something with the money that I’d always wanted to do but couldn’t now do, and the more I thought about it, the more I realized I should spend the money to make something that I had no idea how to market, probably couldn’t produce en mass, was in a field I had little to no understanding of, and more than likely wouldn’t result in any money no matter how I looked at it, and for me, that was a deck-buildy-ish card game.

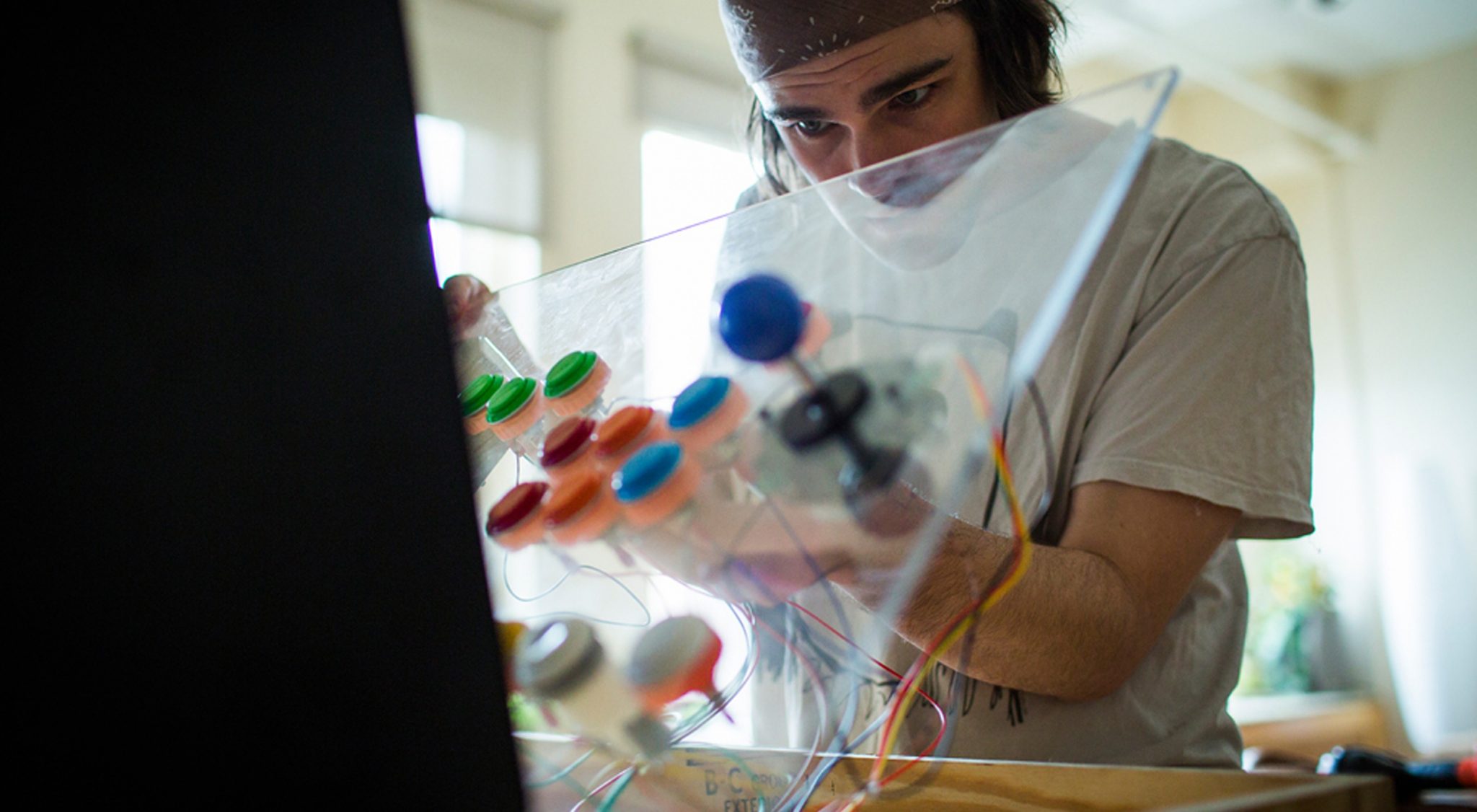

So I spent the money on hiring my illustrator roommate Jess Worby and paying for the first run of decks. It wasn’t until way later that we brought Jesse Fuchs on board to turn it into a real game and help do the kickstarter.

Quinns: Now you’ve actually made a card game, do you still feel like it’s a nightmarish commercial prospect?

ZG: I think this one is still up in the air. Jesse and Jess have gotten paid a pittance for the work they did on Guts and I haven’t taken any money yet. We’ll certainly make a bit if we manage to sell out of our first run, and we stand to make a pretty good amount if the game is successful and we do repeat runs.

The thing is, its all very hard to know! With video games, you can make something in a few weeks and put it out and see if people like it, and if they do, you keep working on it. With boardgames it’s a lot harder at first. We’ve put in more time on Guts than perhaps all the other games I’ve made combined, if you can believe that.

On the other hand, board game work is very front-loaded. If the game is successful, we don’t have to publish updates to support new devices or resolutions, we just keep selling and producing it. Plus, we’ll be able to issue expansions that are much more financially viable.

It feels like making board games is much more like building a brand or a console than releasing a game. So far it’s been a lot of fun, but its definitely more of an endeavor than just making a video game.

Quinns: I’ve heard it said that the hardest part of designing a table game is the final 10% of the playtesting. Was that your experience?

ZG: I think that comes in third to the three all-nighters we pulled to get all the videos done for the kickstarter, and the stress of writing updates where I talk about delays.

The final 10% of the playtesting was rough, but it was more of a thing we could brute force as a group, and that helped out a lot.

Quinns: What caused you to experiment with traditional 52 card decks recently?

ZG: I think 52 card decks have fascinated me for a while because they’re a hellishly difficult context to make something new in. I sort of feel like they’re the “painting” of traditional game design in that they’ve been around for ever and there are just thousands of traditional card games, so finding a radically new game in there is a funny thing to attempt.

What got me into them most recently is how fascinated I am with Poker. I think the most beautiful thing about Poker is that theoretically, I could play it with a group of friends every week for 40 years, have a phenomenal time, learn a lot, get better at the game, and then right at the end, after 40 years, someone new who has never played before can join the group and beat all of us.

That sort of blows my mind. I mean we look at these classic casual-friendly games like Bejeweled or Pac-Man, and they don’t have shit on Poker. Poker is big league famous, like Chess, or Go, but it’s so easy a kid could play it and beat a champion if they got lucky. I want to make a game like that. I mean, obviously that’s not going to happen, but whats the point of a high bar if it’s not as high as it can go?

And as a bonus, I can iterate multiplayer games quickly and share them online without having to write a single line of boring boring boring code.

Quinns: I feel that if you can make a game where players are forced to talk to one another, or even just watch each other, as poker does, 75% of the work is done for you. I think it’s criminal how little negotiation, or even auctioning goes on in videogames.

ZG: Doug Wilson is really into exploring this. I think its hard to do this sort of thing in bigger video games. I’ve seen a few that leverage this stuff pretty well though. Hell is Other People comes to mind.

There’s also a really great game from a few years back where you controlled a single pixel on a field and you along with other people online were tasked with making a pattern as fast as you could, but you had no direct communication.

Way from Coco & Co does a lot with negotiating as well.

Clearly it’s not the direct antagonistic, auction-y or political negotiating that you’re talking about, but its exploring the area a bit.

Ultimately, I think negotiating is a much more widely-used tactic for boardgames than video games because board games are missing action-skills. Talking is like using your mouth in the same way a soccer player uses their feet. Its debating within a defined structure, with a time limit. In video games you don’t need to talk to negotiate, I think Starcraft is in many ways a game of constant negotiation and auctioning.

And yet, I’m sure we’ll start to see this sort of thing happening in videogames sooner or later since it is a fantastic mechanic, and humans are fascinating.

Quinns: You mentioned in your Wired Game|Life profile last year that you felt anxious spending time on videogames, as they couldn’t produce the kind of “wonderful, spiritual moments” you experienced at an art gallery. As a videogamer who’s shifted into board games, I’ve found myself most aware of the hobby’s holy nature when I’m sat at a table with a group of friends. I’ve found my anxiety release valve, is what I’m saying. Are you still looking for yours?

ZG: Thats a super interesting question. I think I never really thought a lot about that feeling until you brought it up just now, and while I do love it, it’s certainly different than how great paintings make you feel.

I think in some ways Kentucky Route Zero: Ep 1 made me feel how paintings make me feel, so in that way, things are balancing out… But more importantly, the more I work, the more I realize that I really don’t know anything about anything, much less, about what is important in life. The best I can do is make the things that I love and follow my interests. I think if we’re taking anxiety release valves, mine is trying to make things that convey the ineffable things that I find beautiful and exciting from my brain into your brain, and until we can plug into each other with gameboy link cables in our ears, my best shot is trying to express myself through whatever craft my brain wants to work on, and right now thats games, maybe it’ll change in the future. Of the little I for-sure know, I at least have figured out that i shouldn’t try to second-guess my subconscious. It’s much smarter than I am.

Quinns: I do a lot of talking (and a lot of thinking when I can’t talk) about the current resurgence of analog games vs. video games. Is that something you perceive too?

ZG: This is definitely happening. The difference is very prevalent in the US.

Most of my friends who don’t play video games love playing tabletop games, and all my video game friends like playing them too. I think its less of a vs. video games as it is a ground swell of hooray-tabletop players. Sort of like how the casual videogame market is dwarfing the hardcore market, but the hardcore people didn’t go anywhere. One thing that did change pretty substantially in console videogames over the past few years is the relative death of local multiplayer on-a-single-couch games. I think boardgames are taking up that mantle a bit.

I think also, people overall are just more into games than they used to be, and with increased understanding comes a desire for new experiences to stretch out your brain. Boardgames are a totally different lens on gaming, and I think people like that.

[Guts of Glory is currently on a boat from China. It can be pre-ordered right here, and if you enjoy unusual designs or laughing out loud, we recommend you do exactly that.]