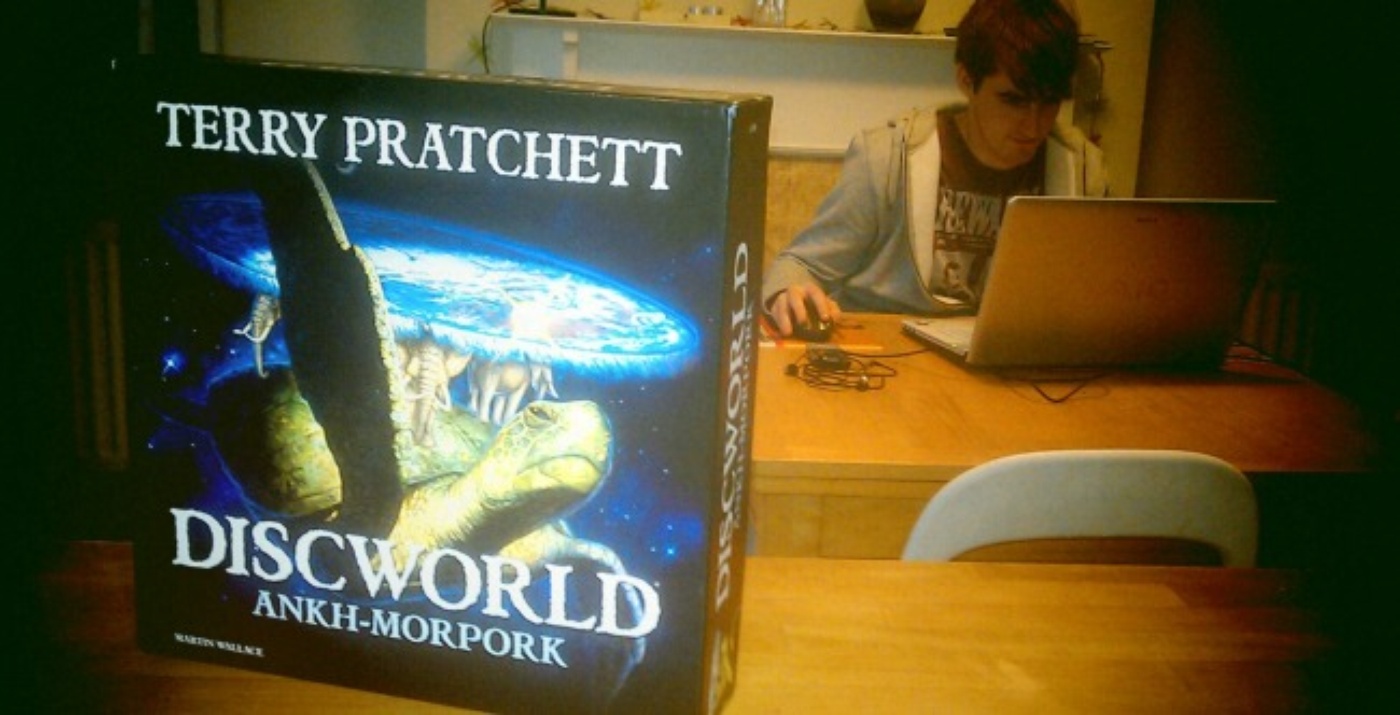

Quinns: TWO games based on Terry Pratchett’s Discworld books have come out recently. Don’t worry, though. We’re here to guide you through this difficult time. There’s Guards! Guards! which we’ve heard is about as much fun as actually being arrested, but there’s also Discworld: Ankh-Morpork, which we heard is quite good! So we got it and played it. Isn’t that right, Paul?

Paul: That’s right Quinns, and-

Quinns: That’s right!

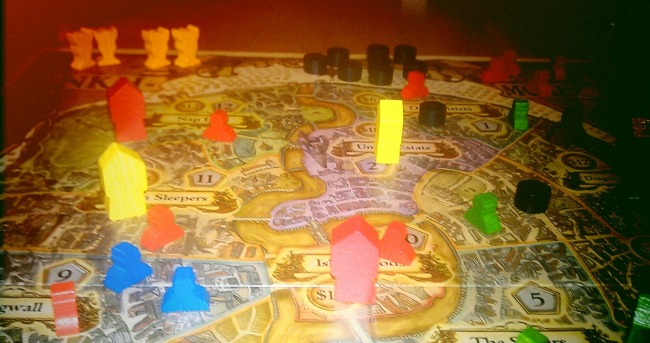

Paul: …so the best thing we can say about Discworld: Ankh-Morpork is that it’s equal parts family friendly and utter chaos, so it’s perfect for a Discworld game. Two to four players are trying to gain control of the 12 districts of the city of Ankh-Morpork, clutching at power with their clumsily, pudgy hands as if they’re all trying to model clay on the same pottery wheel.

Quinns: Fingers slipping over oily fingers, all of you swearing, someone’s got clay in their eye, until finally the thing comes to a stop and all you’ve made is a mess.

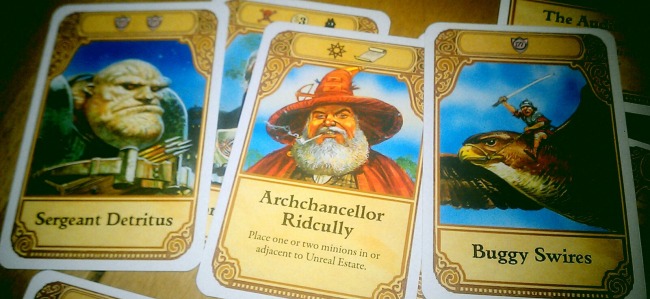

Paul: In other words, Discworld: Ankh-Morpork is exactly like that scene in Ghost, but even sexier, because no-one knows who anyone else is. Ankh-Morpork (the game, not the city) is all about hidden roles, and each role has a different win condition, each needing Ankh Morpork (the city, not the game) to be in a different state for them to emerge victorious.

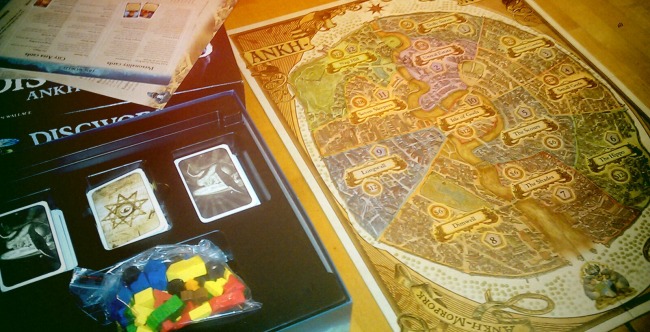

We’ll get to those soon. The game proper is super-simple. You have a hand of five cards, and on your turn you’ll play one of them, triggering a tiny sequence of symbols printed across the top. you might have “Get $5, then place a minion in a district, then build a house in a district,” or perhaps “Place a minion, kill a minion, trigger a horrible random event.”

Money lets you build houses, houses grant you that district’s special power… and minions?

Quinns: Minions don’t do anything.

Paul: Nothing at all.

Quinns: Or do they?

Paul: MAYBE.

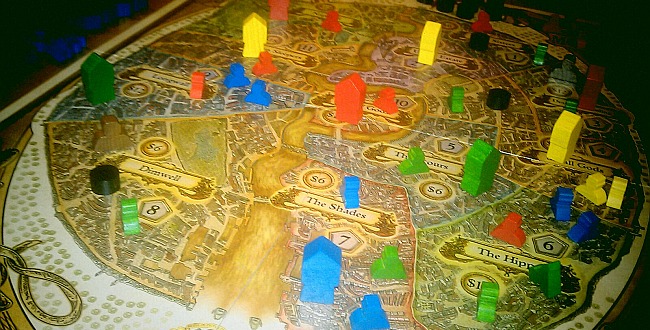

Quinns: Maybe… You see, if you have more of your wooden bits in a district than anyone else, you’re said to “Control” it. Which doesn’t do anything. …OR DOES IT? Some characters will win the game if they control enough districts. Another wins if they can amass $50 (which is actually my win condition we have for running Shut Up & Sit Down). Another wins if they have wood in a certain number of areas (which is actually Paul’s win condition for running Shut up & Sit Down), and yet another character wins if the deck of cards that everyone is drawing from runs out- in other words, if they can stop everyone else winning for long enough.

But because you all picked your characters in secret before the game began, you can only guess what your opponents are up to.

Paul: So immediately you’re trying to work out why the player beside you just did what they did. Do they want to generate money? Are they trying to grab territory? Are they pretending to play like a character they aren’t, to bamboozle you with some sideways kerfuffle? Are they trying to stop you from controlling a district because they think you’re someone that you’re not because you were trying to pretend to be someone else to hide being who you really are because if you are who you are then it becomes too obvious when you-

Quinns: My nose is bleeding.

Paul: But, you see, that’s it. That’s what Ankh-Morpork (the game) is really all about. Pretending. And then trying to sneak your way to victory while hidden under a cloak of deception.

Quinns: It’s the truth. Most of Discworld is spent eyeing the board with the thousand yard stare of a tired troublemaker, watching your opponents snake towards any of several victories as they place a minion here, kill one off there, all of you working to block one another off. Weirdly, this is Discworld’s biggest strength, and, I’d argue, its weakness.

Paul: We’re onto the criticism already?

Quinns: Why not? So here’s the thing. The watching of the board from all these different angles is the fun part of Discworld: Ankh Morpork. It’s clever. It gives the game all the coy smiles and accusations of a budget soap opera. But it also feels like a loose idea, rather than an idea that’s been socketed into a mechanically sharp game. Here, you approach your secret objective… and the other players notice what you’re doing, they play a card that kicks your situation in the particulars, and you’re placed at least two turns away from your victory again.

It’s great how you’re so often tantalisingly close to winning the game. But I was left with the dull feeling that I wasn’t involved in the cut and thrust of a proper card game, so much as I was idly flicking the same cards into a hat, with little consequence.

Paul: Y’see, I’m not sure if the hidden roles is really the problem, I think it’s those cards. The enormous stack of cards that everyone draws from hides all sorts of opportunities, but as it’s whittled down, those opportunities disappear, and the game gets narrower and narrower, and players may find themselves in a situation where the kind of cards they need are all gone. Do you need money? You’re stuffed if most of the cards that generate cash, or let you buy cash-generating property, or that let you demolish property so you can build cash-generating property, or whatever, are all grinning at you from the discard pile.

But Ankh-Morpork (the game) isn’t bad, is it? The rules are so, so simple that you can slide into them like a greased swimsuit, and immediately start strutting about. As any of us would.

Quinns: OK. I know we use weird, pervy analogies a lot on the show, but the idea of a greased swimsuit genuinely upsets me. The tactile equivalent of fingernails on a blackboard.

Paul: Grease Up & Sit Down. The spinoff show. Just starring me—

Quinns: ANYWAY no you’re right. This game isn’t bad. If I’d been run over by a Royal motorcade (again) and a family member brought this to the hospital, I’d prop myself up in bed and play it. It might be the most inoffensive board game we’ve ever looked at.

Paul: I really want to recommend Ankh-Morpork (the game), because it provides such a simple introduction to the very thought-provoking genre of hidden roles and area control, but…

Quinns: SAY IT. DO THE DIRTY.

Paul: …but while the rules are so simple, with these flawless, practically crystalline rules, the bigger picture is of something too lightweight for you to take seriously. It’s a tacky plastic jewel.

Quinns: But it’s fine, isn’t it?

Paul: It’s fine. Ladies and gentlemen! Discworld: Ankh-Morpork, and we mean this wholeheartedly, is a game that literally functions. It’s like the Royal Family. It’s there, it’s quite simple, it’s nice, it’s inoffensive, but we wouldn’t recommend it to you and it’s all about hidden roles because-

Quinns: Because they’re all lizards.

Paul: Exactly.