Hilary: Ross Cowman’s Fall of Magic is, indeed, magical. It’s the kind of game you become immersed in, losing track of time, only to find yourself wandering out later from a rich and compelling world of your own creation. Like some wardrobe-portal to a new and fantastical land, you’ll find yourself yearning to find a way back.

Luckily for all of us, continuing our journey to Umbra doesn’t require any train wrecks or magical paintings. Only one to three other players, and a few more hours of our time.

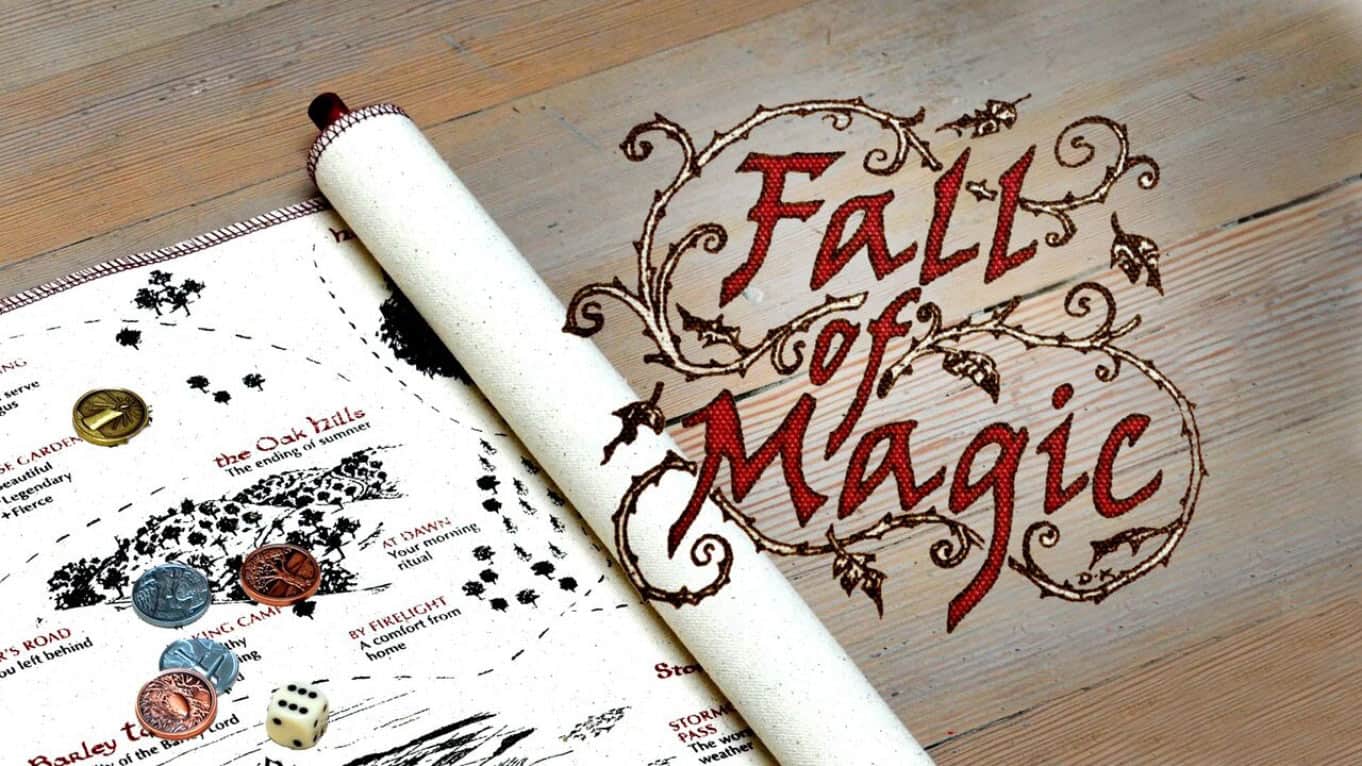

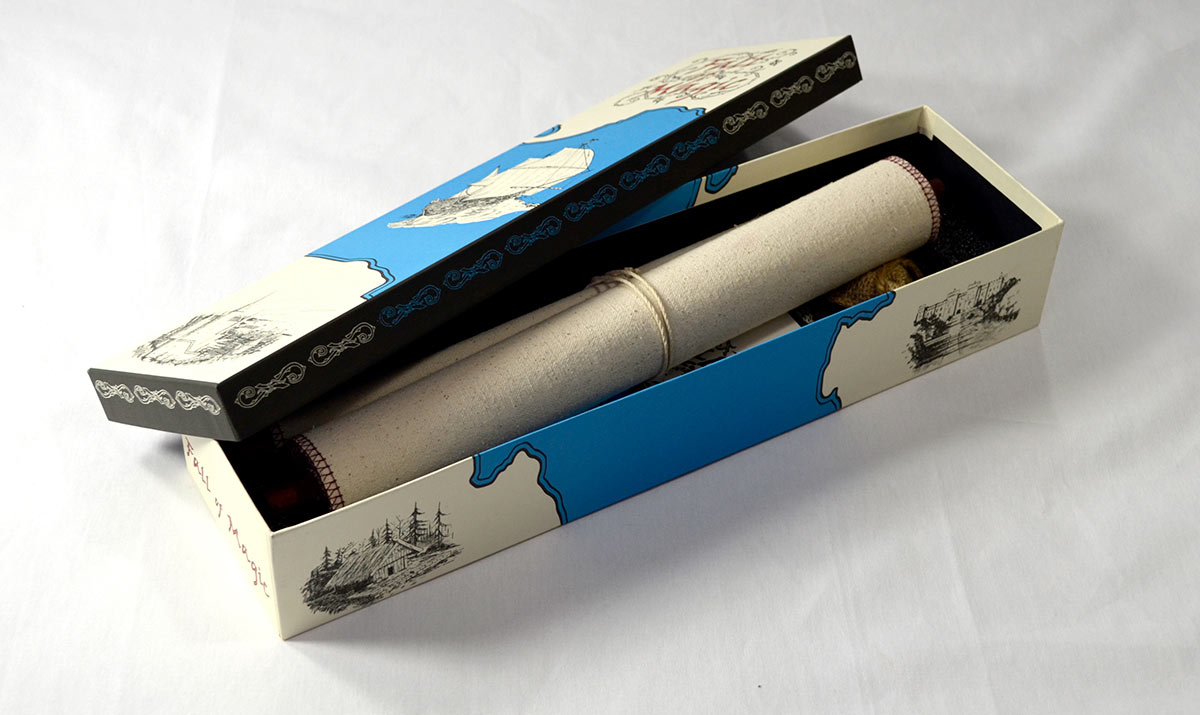

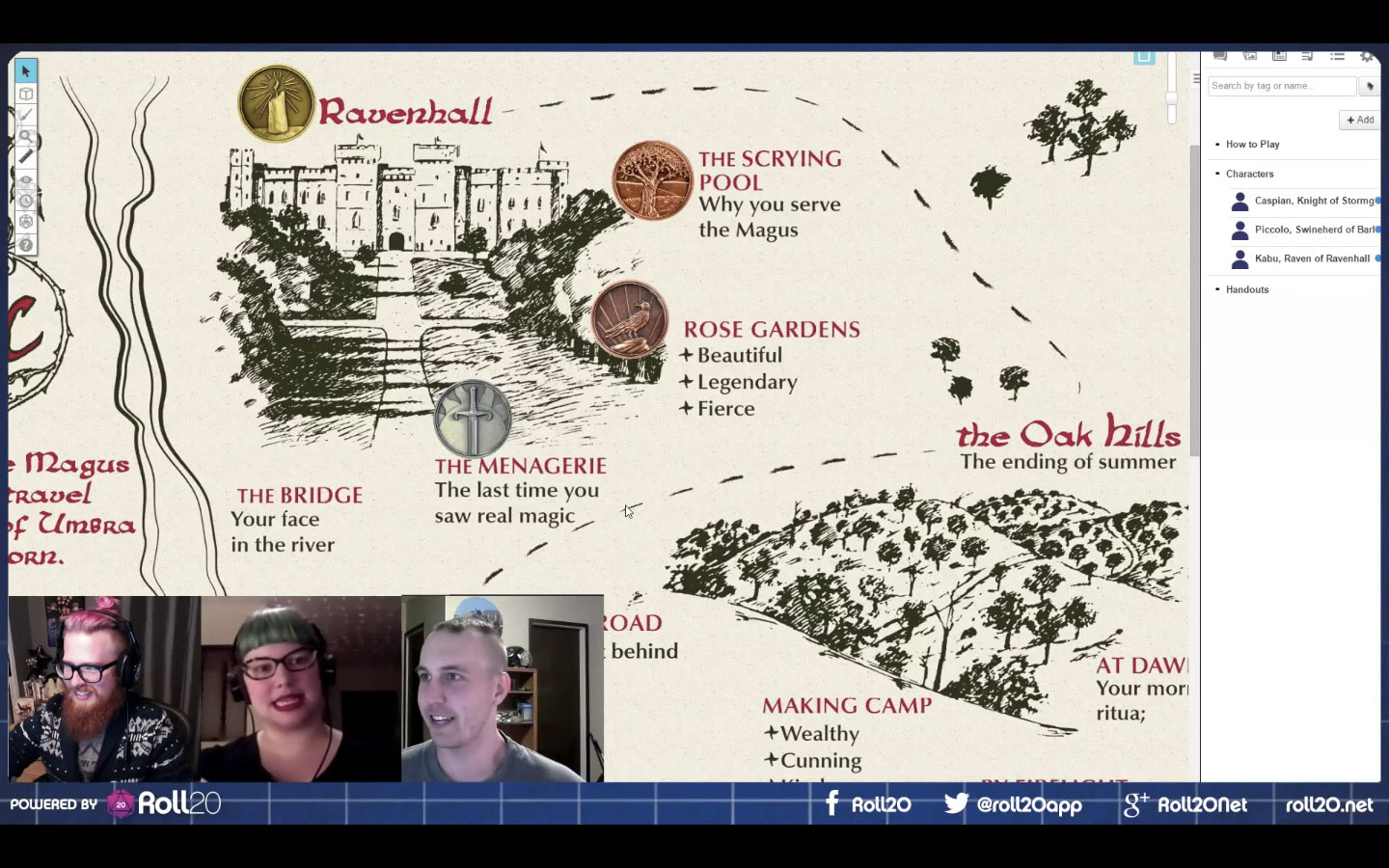

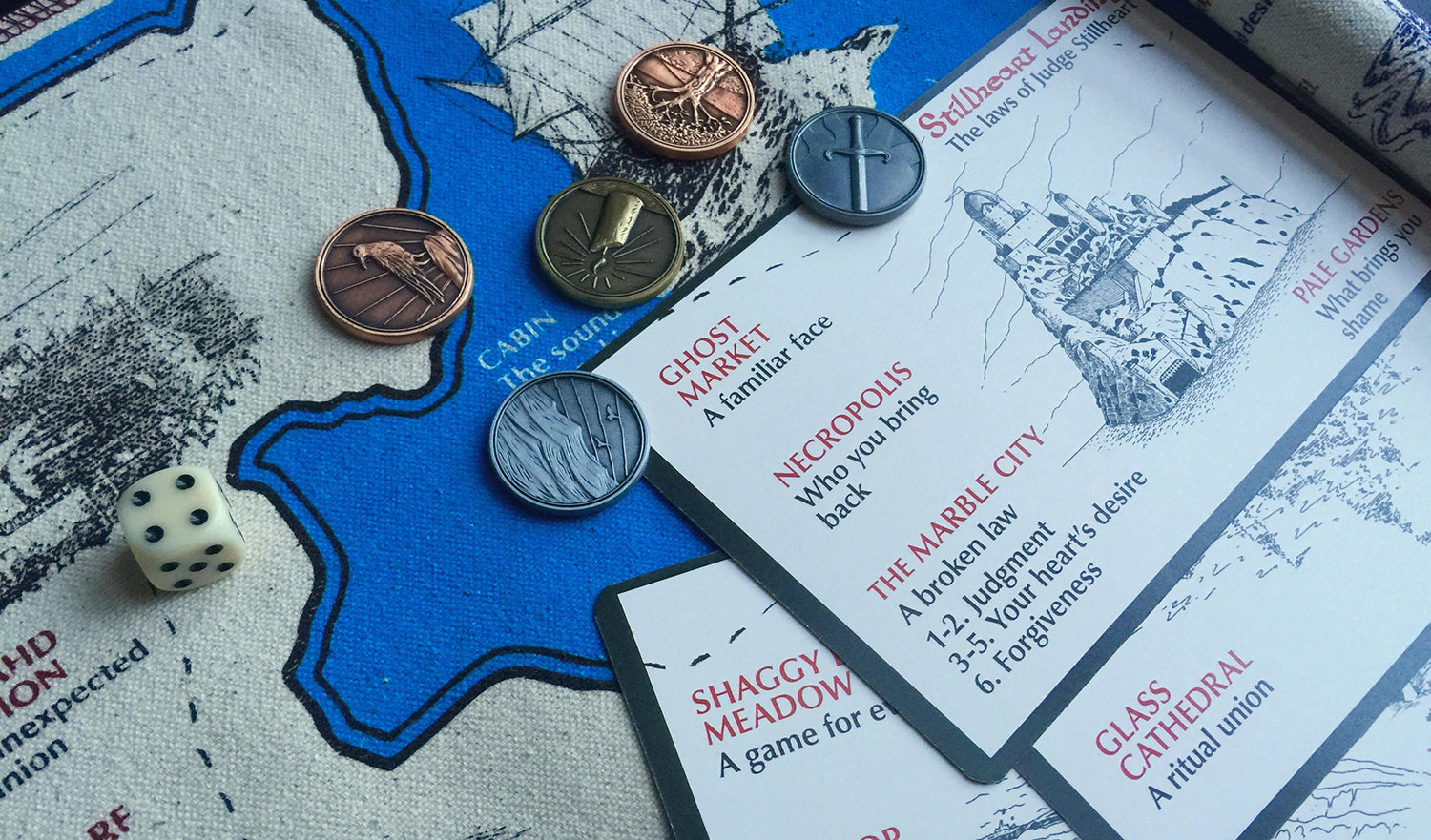

One of the first things you’ll notice about Fall of Magic is that it is beautiful. The physical game itself is magnificently designed. The artwork is evocative, the material items high quality, and everything about the aesthetics of the game enhance and propel the themes and mechanics. Playing in person you can use custom made campaign coin tokens to track your progress along the winding map, screenprinted onto a large canvas scroll that you un/reroll as you play. My game of Fall of Magic was played online, using Roll20, and even there the art and layout and overall design of the digital materials provided an amazing backdrop for the game.

This is a storytelling game much more so than a roleplaying game. It provides you with a sparse but powerful narrative foundation made up of story prompts, character and place names, location illustrations, potential traits and moments of character transformation. There are always things to draw on, but never so much that the game gets in your way.

The premise is simple: magic is dying, you see, and the Magus with it. So we’re accompanying them on a journey to Umbra, where magic was born.

Game play is collaborative. No one at the table has more narrative authority than any other, and all players work together to create our story. In fact, while playing, it felt more like we were teasing out and revealing some story larger than any one of us, which we couldn’t possibly have accessed or invented alone. This is truly a play-to-find-out-what-happens sort of game. Each player contributes through their own scenes and character, but we also all have opportunities to ask questions during other player’s scenes, to add detail by playing our own characters or other elements during those scenes, and by narrating scenes as the Magus.

One of the most pervasive elements of the game, alongside collaboration, is the recurrence of empty space. The game text specifically encourages you to ask questions and leave them unanswered, to introduce things we don’t yet understand. This adds to the rich storytelling environment, where it feels like we’re part of a bigger story, that the scenes we’re seeing and the narrative we’re exploring extend past the edges of our current view. That the world is much bigger than we could hope to completely describe.

The encouragement to create detail without resolving everything neatly means there are always loose ends for other players to pick up, or for us to return to. The story feels cohesive, because we’re each building off all the pieces available, not attempting to tell our own separate or competing stories.

The design of the game is very cohesive. The aesthetics support the gameplay, the themes of basic overarching narrative are supported by the physical objects. We’re telling a story about magic and frankly playing the game feels magical. The characters move ever onwards, propelled by their choices and sometimes changed by them, while we unroll new parts to the map and cover over the road behind us.

The game does a very good job providing us with tools to undertake and enjoy this journey. There are solid suggestions about playing storygames generally and this one in particular: remember that this is a conversation, leave loose ends and empty spaces to pick up again later, think small and concrete, don’t hold on too tight to the story, make room for quieter players, treat everyone’s contributions as important, and so on. So many of the principles of engaged participation that make playing games easier and more enjoyable, but tend to be left out of rule sets/assumed to be pre-existing and separate player knowledge.

If the sorts of things brought up by Cowman in the text of this game feel eerily similar to my own tips and tricks for gaming, keep in mind that both Fall of Magic and my own tabletop roleplay experience are firmly grounded in the context of Pacific Northwest/Cascadian indie gaming. Like many other games from designers in this region, the rules are meant to be passed around and read aloud, and set out to equip even a complete newcomer with basic gaming skills. That said, there are always gaps in knowledge that a game assumes players will fill in themselves.

Fall of Magic revolves entirely around narrating/playing out scenes. The text gives you suggestions on how to start scenes, and story prompts to include, but it doesn’t really give you any assistance or tips around ending scenes. How long should a scene be? Who should you ask to take part? When should you ask someone questions and when should you let things slide? These questions will no doubt come up for players, but as so much depends on the particular game and the people at the table that I think they would be very difficult to answer in a useful, let alone definitive, way.

In this case, however, the game structure means players are likely to start developing these skills in-game. Likely the first few scenes will feel a bit awkward and unnatural, but as you’re forced to frame scene after scene it becomes a bit easier to do—through repetition, trial and error, observing other players’ choices—and you’ll figure out the dynamics of your particular table.

The session I played was with two close friends I’ve gamed with a lot, and we all have a lot of experience with RPGs/storytelling/improv/etc. Since we know each other so well, as people and gamers, our game felt very comfortable and very narratively unified quite quickly. I’ve heard it said that any game, no matter how well or poorly designed, can be enjoyable with the right people at the table, and in my experience that’s pretty true. Some games work with you and some work against you, but ‘fun’ is something a table can make on its own.

Really well-designed games don’t guarantee ‘fun,’ but they deliver on their promises and premise whether you’re playing with a tight-knit crew who can almost anticipate each other’s sentences or complete strangers sitting down to their very first tabletop game. Fall of Magic delivers. Any table of people approaching the game with curiosity, openness to each other’s ideas, a spirit of collaboration, and taking the game’s recommendations on incorporating the senses and concrete details to heart, will be able to tell a wonderful story together.

One of the most powerful things about tabletop roleplaying are the stories we create. Often the stories and the characters and their growth and their secrets are a byproduct of mechanics aimed at exploration or combat or whatever else. Here the mechanics exist only to allow the story to emerge. The whole game is the story.

This is going to appeal to a lot of people, including a lot of people who don’t have a background in RPGs or consider themselves gamers. It’s also not going to appeal to a chunk of people, likely including a segment of those who do play RPGs and consider themselves gamers.

Fall of Magic runs on cooperation and collaboration. If you find that unappealing you may find the entire game a frustrating experience. Likewise, the game and its mechanics exist to support you in telling a story. If you’re waiting for the Real Game to kick in, and for numbers to crunch and stats to optimize, you’ll be disappointed. This is also a game that really does require player buy-in in terms of both sustained attention and working with other players’ ideas. This isn’t a game where you can zone out until it’s your turn; it requires all players at all times.

The stretch goals in the original Kickstarter resulted in additional map areas and artwork, which are now standard to the game, as well as translation into three additional languages. At this point Cowman is selling the high-quality, physical Scroll Edition in English, French, Italian, or Japanese, via fallofmagic.com. The Digital Edition from the same site includes all the maps, cards, and instructions as both ‘print & play’ and ‘online play’ packages for all four languages, as well as full colour and two-tone tokens. The English rules are also available as a free PDF, and will give you a glimpse of the style and quality of the overall game.

I’ll note that the aesthetics of the existing materials guide the table towards a particular (though fairly wide) variety of fantasy story. There’s plenty to play with there, but a table could also decide to focus or shift the narrative flavour by agreeing to some common inspirations or thematic elements before starting play.

I think this game is a real gem. I can imagine playing it with my parents, with my friends and their kids, on a date …okay, maybe I like different dates than you do. My point is that Fall of Magic is simple enough mechanically to appeal to and be accessible to a wide range of people, of varying ages and varying backgrounds in tabletop gaming.

Certainly the make up of players at a particular table will greatly influence the game, but that’s part of its replayability. Not only are there always names you didn’t pick, and vocations you didn’t come across, there are paths on the map you never took and likely scenes and story prompts you never played out.

Even if you were to play Fall of Magic with the same group of people every time you would still come out of it with a new and different story. And that’s the true magic of it. This game is a careful collection of rules and suggestions and objects and art meant to help you tell a story. A story you’ll be captivated by. A story you’ll reflect on well into the future, with bits and pieces you’ll wonder about, characters you’ll remember with fondness or curiosity or regret.

Order it for yourself. Unroll some magic.