Quinns: One leathery fruit borne from the article on my board game collection was a lot of people telling me to finally play Lancaster. “It’s a classic,” they said. “I’d never turn down a game of Lancaster,” they said.

We’ll get to what I thought of it, but first I owe this game an apology. I realise now that I’d mentally compartmentalised Lancaster in the same place as Alhambra- a weird box that was continually being printed by Queen Games long before Shut Up & Sit Down began, that would be printed long after we’re gone.

I remember finding a copy of Alhambra Big Box in my friendly local game store in 2013. “What is that game?” I asked a staff member, and we both gawped at it as if it were the monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey.

“I… don’t actually know,” he said, as if it was the first time he’d seen it. To this day I still don’t know what Alhambra is.

(Pay a visit to that game’s BGG page if you don’t believe me. You’ll come away knowing less about that game than when you went in.)

To my unending shame, this week I found out that Lancaster was released in 2011, meaning that instead of being an unknowable artifact it’s the same age as SU&SD. It also has a much better reason for being in print than some of Queen Games’ catalogue: Lancaster is a very, very good game.

For reasons I’ll get to later we’ve decided not to give Lancaster the full review treatment, but I still want to put this game in front of you guys and girls and tell you about it. Good lord, it’s a good game, and fittingly it’s a good game about being a good lord.

2 to 5 players each control noble families aspiring to greatness in 15th century England. You can spend your turns dispatching your knights to different counties, claiming rewards that you’ll funnel back into your knight-dispatching engine, or, more excitingly, you can send the same knights to join the war in France. This gets you victory points, with the trifling catch that those knights might be horribly killed.

In other words Lancaster is a “worker placement” games like Caverna or Tzolk’in. In these games players race to claim different spaces on the board that their friends might want, resulting in a game with a lot of competition but where you’re blocking people rather than directly attacking them.

Critics of the genre will tell you it’s a lonely way to play games, whereas people who like it will point out that once you remove your pesky friends, players are free to engage in immensely complex puzzles.

…That’s usually the case, anyway. Lancaster’s take on worker placement is smart enough as to break my heart, because someone created this in 2011 and none of the smash hits copied it. In fact, this is my favourite interpretation of worker placement ever. Stick that in your cannon and smoke it.

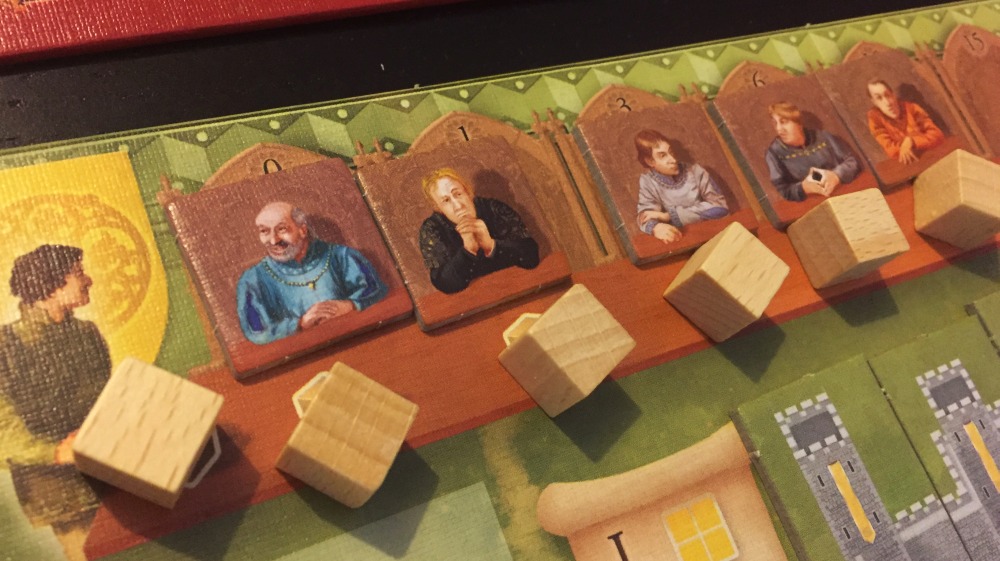

Here’s how it works: Your Knights in Lancaster aren’t created equal. You start with a “1” knight and a thicker, more intimidating “2”, and in addition to claiming more knights as the game goes on you’ll be upgrading the knights you have, gradually fattening up each strength 1 square into a cube, which is strength 4 (which, in 15th century England, was the highest and most secret number).

You want to upgrade these pieces because any knight that’s been placed on the board can be kicked back out of a space by a knight with a higher number, meaning the first player gets their knight back and has to place it again. Only once this bumpy game of musical chairs has come to a complete stop do players get the rewards they claimed.

But wait! There’s more. Players also have a resource of “squires” hidden behind their screen, and when you place a knight they can be put down with any number of squires, each of which add +1 to the knight’s value.

…But wait! Just one more rule. If a knight with attached squires leaves a space, either because the turn’s over or because they were ejected from that space by a bigger knight (or one with more squires), any squires attached to them are lost when you take the knight back.

Oh, oh, oh, it’s so good. Straight away you get a game that’s five times as interactive and juicy as an ordinary worker placement game. A taller knight coming along and bouncing another knight out of a space has a sense of humour to it, especially when that knight immediately goes and bullies an even smaller knight.

Squires are even better! Spending squires is an electric little play that causes the whole table to pay attention, since you want to pour in just enough squires that nobody’s going to take that space back from you and lose you your investment. And there’s also a fascinating puzzle to do with the value of upgrading your knights, which gives you a stable kind of power, versus collecting squires, which gives you mad, unpredictable strength.

But most importantly of all (and you guys have heard this one from me before), you’re playing with your friends. We’re now a million miles from the impersonal misery of worker placement where someone takes the space you wanted and you say “Oh” and get annoyed. Lancaster gives you the tools to need to come sprinting back to that castle with four squires and take it back, and then everyone wins! You get the space you wanted, your opponent coaxed you into spending resources and the rest of the table gets to giggle at your sordid scramble.

Over in the corner of the board (pictured above) the way you send knights to war in France is just as silly and thought-provoking.

In a nutshell, it’s an area control game where the person who sends the most knights to each battle gets the most victory points. Only if you win the battle, though. If you collectively don’t reach the required strength, the battle card and all the immensely valuable knights stuck to it continue to slide towards the edge of the board, like a raft heading towards a waterfall, and if those knights don’t receive enough reinforcements for a second turn all the knights get ransomed back to their owners.

“What happens if we can’t afford the ransom?” your friends will ask. “Do we get negative victory points?”

And I recommend pausing for effect before you deliver the answer. “Oh, no,” you say. “They’re killed.”

Again: Fun! Interesting! Tense! Funny!

The final mechanic I want to cover is a little clunkier, but we couldn’t leave it out of a tour of Lancaster’s best bits.

To one side of the table sits the Law Board, displaying three laws. Stuff like “Whoever has the most squires can upgrade a knight,” or “For every two knights you have in France, you can upgrade your castle” (the castle being a personal side-board that produces rewards every turn).

But waiting in the wings are three more laws, and at the end of each turn before the current laws have their effect, you all have to vote on each of the new laws in turn. If the table votes down a law it’s discarded without effect, but if you vote it in it bumps an existing law off the track on its way in.

So far, so “Oh god what are all those cryptic symbols off to one side of the board, they don’t look like fun.” And you’re right! They’re not fun in and of themselves. But what is fun is that players vote on the incoming laws in a blind bid using vote cubes, which are a resource you generate by collecting councillors from around England.

This law track is often entertaining for the same reason that blind bids always are, with one player inevitably dropping tens of cubes on the table as you all open your fists because they thought that another player would vote just as heavily, when in reality they didn’t bother. But what makes it particularly interesting, tactically, is that players with lots of councillors get to control what the game of Lancaster is. It gets especially good towards the end of the game when the law-makers can decide whether spare squires and coins are worth victory points.

But of course, everyone’s squires and coins are hidden behind their screens… !

Taken as a whole, Lancaster is a perfectly strong little game. It’s straightforward, it’s quick, and the puzzle is fierce and host to a distressingly large quantity of good ideas. I really liked it, and if you like the sound of this box I think you could feel pretty safe buying it.

But as I said above, we won’t be giving it the multiple playthroughs and days of scriptwriting that accompanies a Tru SU&SD review.

There are a couple of reasons why. The first is that the expansion’s out of stock (although the Big Box with the base game and expansions is still available in America), which really hurts a game from 2011 which has little aspiration to be different each time you play. Modern games tend to be a little broader in scope and more eminently replayable, so without the expansion Lancaster feels… not thin exactly, but a far less exciting purchase than SU&SD’s favourite German-style games.

On that subject, the bigger reason we’re not reviewing Lancaster is that we want to focus on our exhaustive review of a different German game that we’ll be publishing next week.

But we wish Lancaster the best. Long live the king, indeed.