Quinns: After playing co-operative social deduction game Deception, the proof is insurmountable. The 21st century police force is the greatest board game theme of all time, not because it works so well but because it doesn’t work at all.

Back in our eighth ever podcast we talked about Police Precinct, and while we had a terrible time with that game we were endlessly amused because we seemed to be playing the cast of Reno 911 on the set of The Purge. Then last year I finally got to try Good Cop Bad Cop, where in one memorable turn I confiscated my colleague’s coffee as evidence, downed it in one gulp, then shot them.

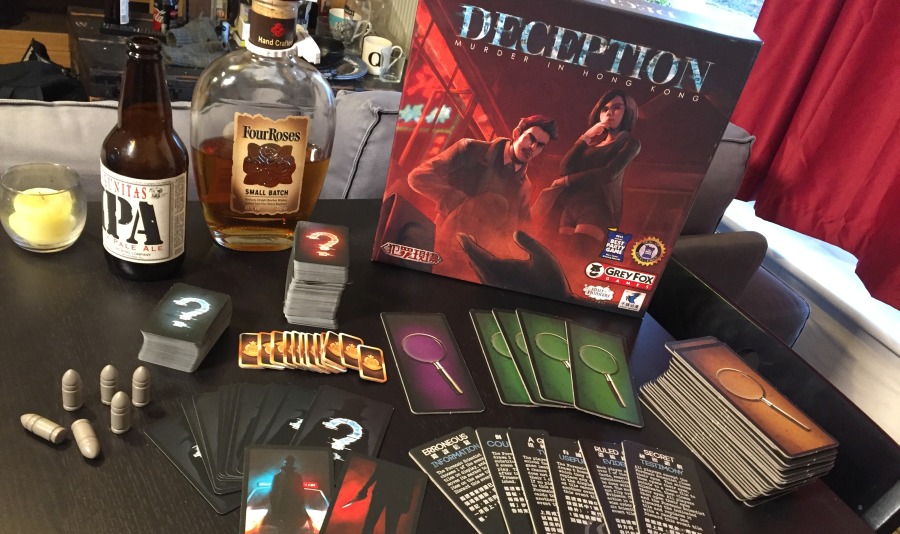

But with a name like “Deception: Murder in Hong Kong” and brooding, maroon box that includes a handful of plastic bullets, you might assume that this, at last, is a serious game about law enforcement.

You couldn’t be more wrong. I’m thrilled to say that Deception is every bit as silly as those others, and it’s also the best game of the three. Come for a ridealong with me! You’re statistically unlikely to be shot.

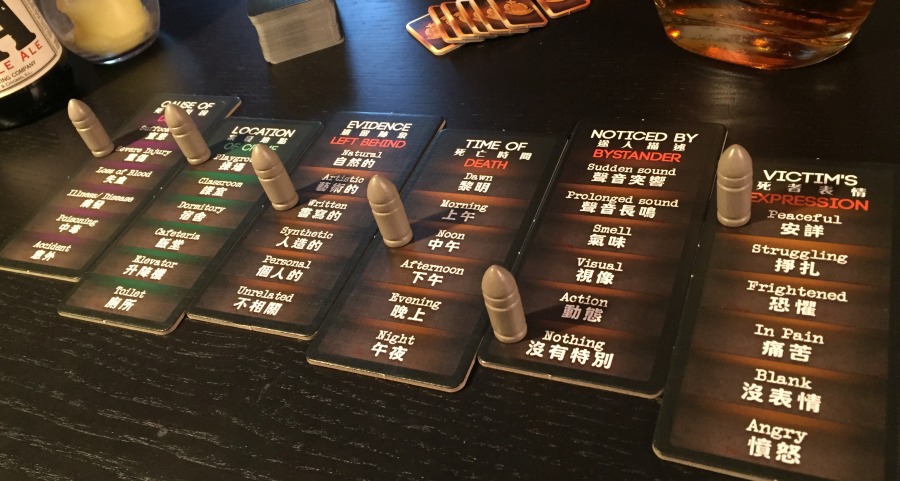

In a nutshell, Deception is a gory hybrid of Mysterium and The Resistance. 4-12 players represent Hong Kong’s finest, and out of them one player is chosen to be the Forensic Scientist. Everyone else is dealt four lovely little “murder weapon” cards and four “key evidence” cards, creating a grim, criminal scrapbook on your table. These players are each dealt a further card, letting one of them know that they’re secretly the murderer(!) who wins if everybody else fails to solve this case, though for all extents and purposes the murderer will appear to be playing the game like a normal police officer.

Everyone then closes their eyes except for the forensic scientist, who instructs the murderer to open their eyes. The murderer does so, revealing themselves to the scientist, and the murderer points to one of the four murder weapons in front of them and one of their four pieces of evidence.

The forensic scientist – who from this point on can’t speak – then places his or her plastic bullets on six randomly chosen tiles, trying to guide the rest of their team to identify the murderer’s weapon and evidence. Like so:

And that’s it! After this lightning-fast setup you’re off the to the races, if one of the racehorses knew how to win the race but couldn’t speak and another racehorse was a massive liar.

The rest of Deception is simply the players discussing what the scientist’s clues mean, the scientist getting two chances over the course of the game to replace a clue tile of their choice with a new one, and the officers each deciding how to spend their one guess.

This is by far Deception’s funniest rule. Each player is given the world’s tiniest police badge, and when you want to try and solve the case you must declare “Let me solve the crime!” You then get to point at one weapon and one piece of evidence around the table (both belonging to the same person, obviously, because that’s the restriction the murderer faces).

If you get both cards right, congratulations! Everyone but the murderer just won the game, and you are presumably hoisted up on the shoulders of your colleagues and someone runs out to buy a bodybag-shaped cake. But if you’re wrong, or you only got one of the two cards right, the forensic scientist simply says that you’re incorrect and takes your badge.

For the rest of the game you’re relegated to simply trying to persuade other players how to spend their guesses, bringing to mind a now-unemployed police officer bothering their ex-colleagues as they leave the police station. In one of my games of Deception a player was so convinced that “ants” was the key evidence that he earned the nickname Dr. Ants, a character that persists in our imagination to this day.

Speaking of fun things you can do with Deception’s theme, I thoroughly recommend looking at the eight cards in front of everyone as stuff that is owned by their police officer. So you’ve got one person sat at his desk with some pills, wine, a dirty shirt and pockets full of sawdust, while someone else has a bag with a rock in it. Then when the forensic scientist says the victim was killed by blunt force trauma, you get an exchange like this-

Wine man: Oh my god it was absolutely you. You couldn’t resist using your rock that you keep in that bag.

Rock guy: Ha ha, it wasn’t me. Look, the victim died in a library. I’m not going to use my rock in a library, am I? That’s not how you use rocks.

Lady who is covered in ants: You would know how you use rocks, wouldn’t you? Hardly a day goes by you don’t dream of bashing someone with your rock. Admit it!

Rock guy: Go away you’re getting ants everywhere

But I appreciate that not everyone is going to want to roleplay Infernal Affairs as interpreted by Harold Pinter, so I’m happy to say that outside of this inherent absurdity Deception is just a really good game.

Like Mysterium, Deception offers a fun, easy-going puzzle that’s tremendously satisfying to solve. And like The Resistance, there’s a lovely sense of tension and electricity that comes from knowing that anything anyone says could be the mole trying to coax your imagination away from the solution. If I’m honest, I was ready to be cynical about a game that’s so obviously a mash-up of mechanics from other games rather than something truly new, but actually, Deception doesn’t feel like either of the games that inspired it.

First let’s compare it to the supernaturally awesome game of Mysterium. Unlike Mysterium, where the ghost hands out abstracted dreams to help people pick criminals out of a lineup, Deception asks very gritty, granular questions of the forensic scientist that means they need to picture the crime in far more detail.

For example, the murder weapon might be “Fire” and the evidence “A spring”, and one of the tiles you’re given asks you where the crime took place. Deception thus forces the forensic scientist to invent a real-world crime from a prompt of two cards, so in the previous example, maybe that’s a mattress fire. It’s a delightfully weird proposition- in order to use these crumbs of language to steer the detectives towards the correct pairing of cards, the forensic scientist first has to commit the murder in their head, a crime far more graphic and detailed than the murderer ever imagined- they just hastily pointed to two cards, after all.

And unlike The Resistance – a game I stopped getting down from the shelf because of the unbelievable stress involved – being the murderer in Deception is a pretty low-stakes prospect, because you don’t have to lie as much as try and solve a puzzle while ignoring the fact that you know the answer. But more importantly, since everyone knows that the cards in front of them can’t be the solution, everyone ends up looking a bit shady.

This last rule is what gives Deception a sort of low-voltage electric current that runs through negotiations. Since everyone knows (and the murderer feigns) that the answer isn’t in front of them, nobody can suggest any theory without another player having to roll their eyes and afterwards say “Yes right except that can’t be true because I AM THE POLICE,” a lovely bit of kabuki theatre that is as important as it is stupid.

There’s a similar jolt of energy, like someone’s taser accidentally going off, when anybody tries to solve the crime. Something I’ve said before is that for all the challenges offered by modern board games, it’s disappointingly rare that players get to perform a play that’s shimmeringly brilliant. Solving the crime in Deception – pointing at a combination of two cards from the 112 possible combinations in an eight player game, and being correct – feels absolutely amazing. But more often than not you’re simply wrong, and the whole table breathes a sigh of frustration (and one person a sigh of relief) as you’re relegated to the unemployed men and women standing outside the police station, yelling about ants.

Wine man: Did you try and solve the crime? It was the ants, right?

Rock guy: GOD DAMMIT – listen, it has some combination of poison gas and a mobile phone!

Wine man: OH MY GOD

Player that is actually still in the game: WILL YOU BOTH SHUT UP

There’s another feature packed into this box that we haven’t even talked about that introduces Merlin from The Resistance: Avalon into the mean streets of Hong Kong- a Witness who knows who the murderer but has to keep their identity a secret. But an even nicer surprise than this is the sheer quantity of cards you get with the game. This box is a madman’s trove of murder weapons, forensic tiles and creepy evidence, with slightly more of all of it than they needed to include.

Overall SU&SD absolutely recommends Deception: Murder in Hong Kong, with a couple of caveats. While I think you could happily own both this and Mysterium, I’d still recommend you buy the latter first. Deception’s great for a quick thrill, but the latest edition of Mysterium with Asmodee’s stunning art design is one of the grandest, most gorgeous games ever made.

I’d also add that while Deception claims to seat 4-12 people, not unlike The Resistance, I probably wouldn’t play it with more than 9. Arguing and discussing becomes a lot less entertaining when theories and lies can go unnoticed, and you’re waiting for your turn to speak.