Paul: I can’t remember the last time I angered so many people so quickly. The last time I broke so many promises, stepped on so many toes, turned on so many friends. Maybe I never have before. Maybe a board game has brought out the very worst in me. Maybe my ambition has finally overcome my morality.

Was it worth it? Was all the bloodshed, backstabbing and brutality justified in service to my thirst for cardboard conquest? Would I do it all again? I just might, so take a seat and let me tell you all about Battle for Rokugan.

First, I just can’t go on without acknowledging that this game has a very obvious ancestor, the aged but still healthy relative that is Game of Thrones: The Board Game. Veteran readers may remember that we reviewed this nearly six and a half years ago, a time so far back that I couldn’t tie my own laces and Quinns had never been out of Hammersmith. We’ve enjoyed it over the years and its bald butchery remains beloved by many, but against more contemporary titles it’s both overlong and overwrought.

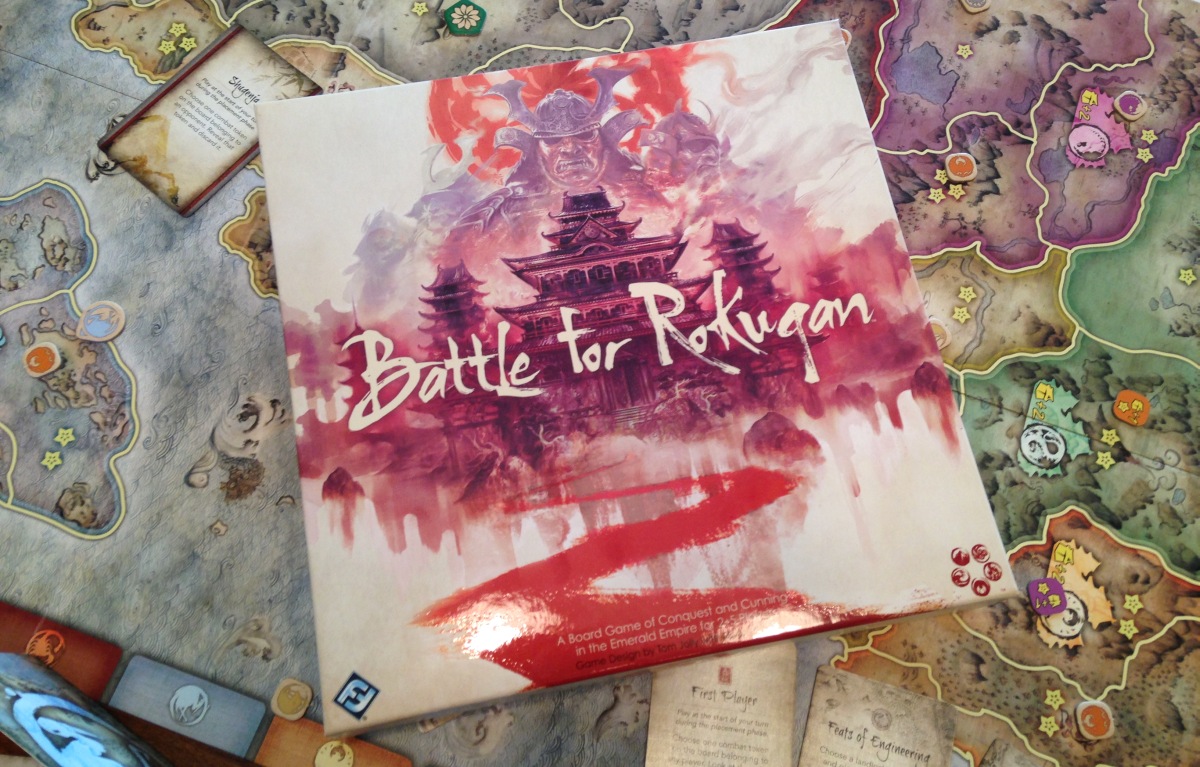

So like a fussy teen trying to ditch uncool dad, Battle for Rokugan distances itself from its forefather as much as possible. It has a much faster playing time, with a full game of five ending in two hours or less, it adds a bunch of simple powers and variables and, much to our surprise, it also ditches the gloss and the plastic.

While Game of Thrones: The Board Game looked appropriately ostentatious, with its marbled knights and elaborate art, Battle for Rokugan has this sort of pastel, washed-out feel. In all honesty, when I first unfolded this map of gentle patterns and light tracing my hindbrain yelled “YOU ARE LOOKING AT A SHOWER CURTAIN.” It doesn’t help that the cardboard tokens used for things like armies, navies and territories are all flat and greyish. It’s not that Battle for Rokugan is an indistinct game, as you can tell what’s going on most of the time, but it does feel like it’s trying extremely hard to be as gentle as possible.

But don’t for a moment let this timidity of tone trick you. Three to five players crammed into the continent of Rokugan is less a knife fight in a phone booth than it is a katana party in a corner cabinet: fierce and furious from the start.

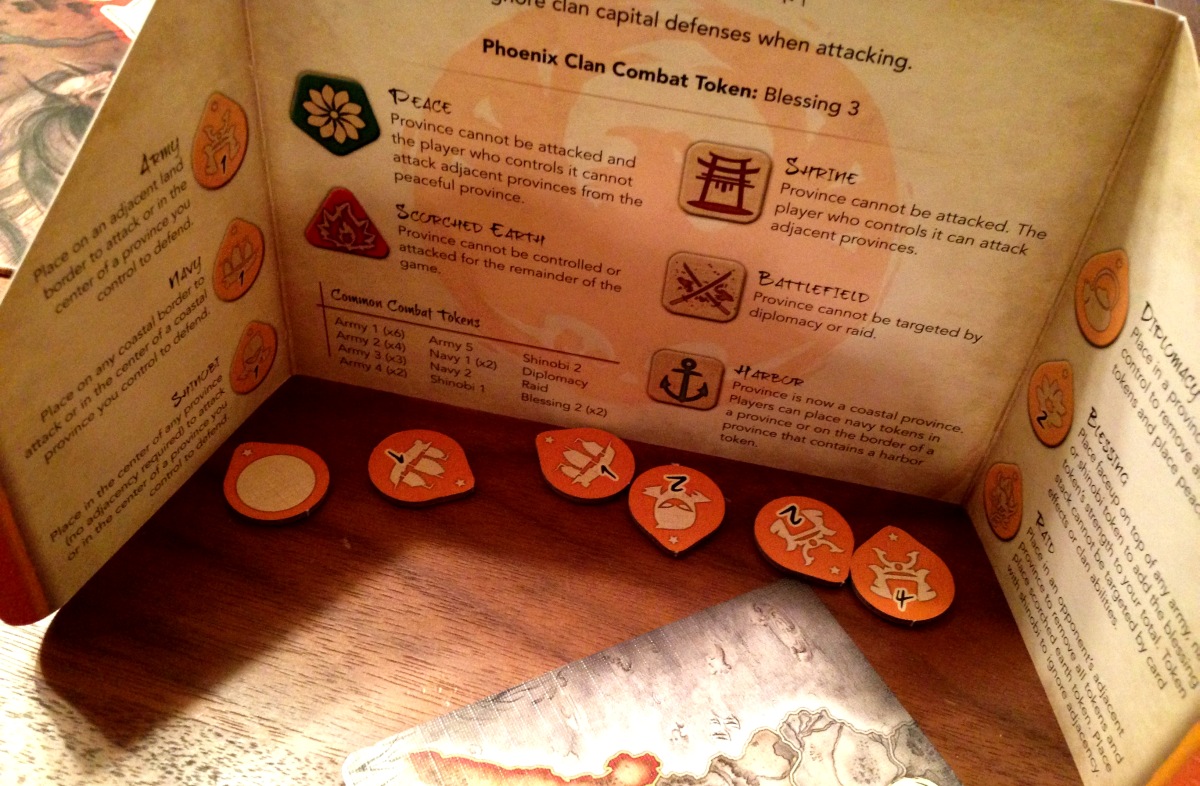

After deploying to their clan’s starting areas, plus ANYWHERE ELSE on the map they like, each player draws from a pool of face-down tokens that represent different strength armies and navies, as well as special actions. Squirreling half a dozen behind their screen, they may find themselves looking at a diplomacy token, a two point navy and a few one point armies, as well as their blank bluff token. Each clan’s token pool is very slightly different, with the brave Lion clan boasting the only six point army, or the conniving Crane having an extra diplomacy token, but I wish there was more variety to these. They’re almost identical.

These tokens are both the attacks and special actions they can take that turn, but also the tiny cogs that turn the wheels of this game, the foundations upon which everything else is formed. If these tokens show high-value armies, these will do great defending a home province or striking out to new lands. Navies can attack distant coastal regions. Stealthy shinobi can be deployed anywhere, attacking from within as if they had burst out of the ground. And, of course, the objective is to conquer provinces to score points, which some being more valuable than others.

Conquering a province is as simple as deploying attackers with higher values than those defending but, since everyone is taking turns laying those tokens face-down, it’s impossible to know exactly how powerful anything might be. Then there’s that bluff token, which has no value at all but looks exactly like an invading force or a sneaky shinobi. Once everyone has deployed their tokens, they’re revealed and resolved, an inevitably enraging experience. One player has fortified a province that was never in danger! Another has wasted their most powerful against a weakling opponent! It’s a quick resolution as each player deploys just five tokens, retaining their sixth.

Just five! Five randomly-determined actions across all of Rokugan per turn, actions you may even resent. Compromises. Right from the start, this game doesn’t so much demand its players make hard choices as make downright hair-tearing ones. Did you want to seize the eastern isles? Sorry, you didn’t draw any navies. Or defend against a massive attack from the south? Not with armies as tough as tall grass. And once those tokens are played, they’re discarded. Only your bluff returns to you so, every turn, it’s now or never. Over and over.

While some players are going to see this as an ongoing challenge, others are going to find it immediately frustrating. Randomness aside, five tokens hugely limits your ability to both attack and defend, meaning you’re both perpetually vulnerable and restricted in your ambitions. There’s a constant feeling of fragility, everyone remains a target and there’s always something exposed.

Good.

It’s almost impossible to turtle, to play in a way where stack up your defences, but so too is it impossible for anyone to steamroll and to construct long, elaborate strategies. The game changes turn by turn, new plans developing as new tokens are drawn. You almost can’t help but turn on your neighbour, break that tacit agreement you had or suddenly launch a surprise attack at the other end of the board. “My tokens forced my hand,” you say. It might even be true.

If this alone were Battle for Rokugan, it would already be an interesting proposition, but there’s a little more pastry on this pie. My favourite mechanic (in not just this game, but perhaps any I’ve tried in months) is a simple rule stating that, when a province is successfully defended, its defence value increases, as does its points value to the player who holds it. Like so:

Fail in an attack and you not only embolden the defenders, you also award your opponent a point. Choose your strikes carefully.

Then there’s everything that doesn’t involve fighting. Playing a diplomacy token prevents anyone from attacking into or out of that province for the rest of the game. Shinobi can attack distant regions, sure, but combine them with a raid token and they can put them to the torch, razing a province for the rest of the game.

Here’s a province that I razed earlier!

Everyone drawing these tokens at random means you have no idea when part of the board might suddenly be obliterated or locked down for good. Your own fortress, with its defensive bonus and point value further bolstered after repelling multiple attacks, could burst into flames in the final turn. THIS IS HORRIBLE.

And no, not everyone is going to like this. Sure, it means everything remains tense and uncertain until the final token is flipped, plus it also allows for wild swings in power and control, but it does mean Battle for Rokugan is as much a game about adapting to chaos as it is about forming any grand strategy.

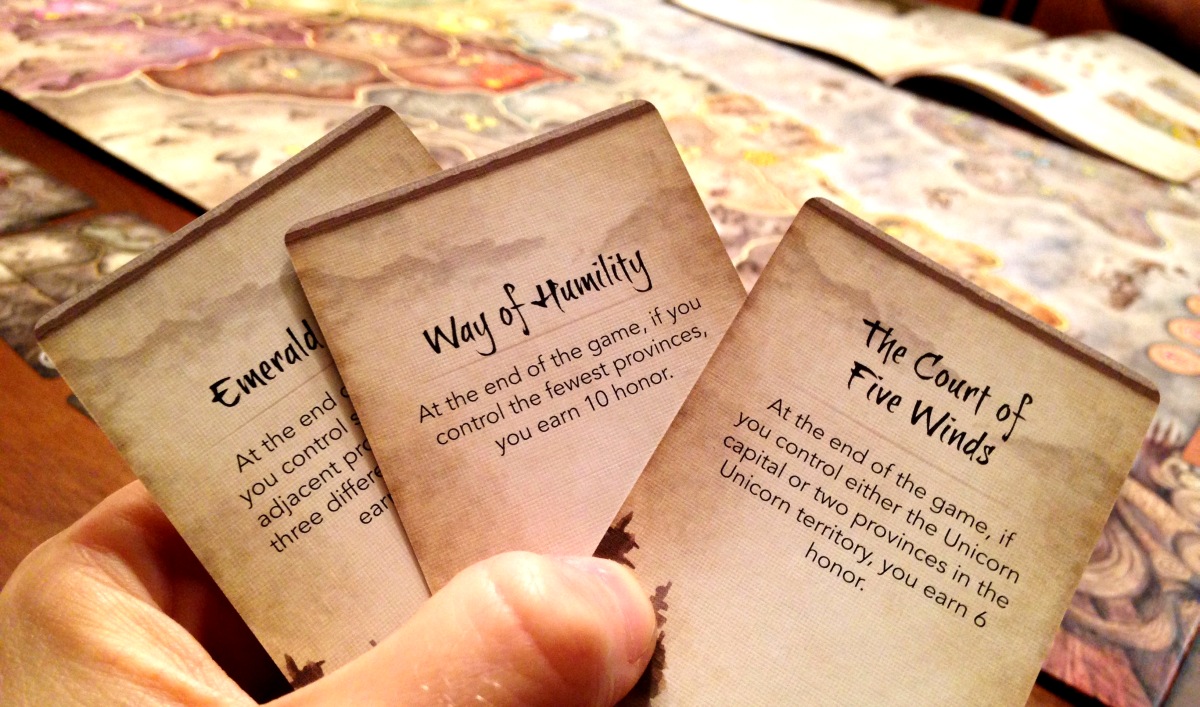

Each player sits on a secret bonus objective that is also as random as anything else. One gives you an impressive six extra points if you control a province that may have already been your well-defended capital when you began. Another awards you ten if you control one province in each of the game’s coloured territories. You’re quite right if you think that one of these may be disproportionately easier to achieve.

But my problem with Battle for Rokugan isn’t that it’s very core is randomness and chaos, it’s that I just think there are other games of area control and conquest that do combat or or deception or asymmetry better. Apart from small powers and slightly different token piles, Battle for Rokugan barely distinguishes its factions, while its central mechanic is the very antithesis of strategy. You can win because someone else had a moment of powerlessness, or lose because a failing opponent pulled a lucky draw. Don’t get me wrong, I do like this unpredictability and I do very much like this game, BUT (and this is a mighty interjection for which you should brace yourself)…

I juuuuuust don’t like it as much as its rivals. There’s our evergreen excitement for Inis and its cousins, Kemet and Cyclades. Inis’ card drafting is a better way of combining both randomness and control, knowledge and ignorance, while Cyclades and Kemet’s huge variety of unusual powers and possibilities make them as replayable as this game’s unpredictable hiccups, but with more grace and dignity. Chaos in the Old World, though not one of Shut Up & Sit Down’s very favourites, really doubles down on asymmetrical warfare. And El Grande, if you can find it, remains the imposing monarch of the area control genre.

BUT (and here comes that mighty interjection again, returned like a shuttlecock serve), Battle for Rokugan isn’t just more affordable than all of those games, it’s damn good at what it does. It plays fast, it plays loose, reckless and relentless, and it will absolutely get everyone around the table animated, angry and angsty about their armies. While it’s not the finest example of its kind, which means I don’t want to give it our coveted Recommends badge, it’s a strong and distinct addition to the genre.

So if you’ve already bought everything listed above, if you just must have more games of this type and and if you insist on spending more money, it’s what you buy. Battle for Rokugan isn’t a wargame I’d tell anyone to get first but, but if you absolutely demand more, it’s the one you get next.