Ava: Welcome to an occasional series introducing you to a single, storied game designer. Today I want to tell you about the games of a man called Carl.

Certain designers have a set of obsessions that shine brightly when you put all their work together. There’s a pattern of passions that unite their work. Carl Chudyk is my my board game design crush, and it’s because he ploughs a furrow that nobody else could. His games are relics from a weirder, smarter world. He builds layered puzzle-systems where possibilities multiply at every turn. They’re challenging to learn, but a delight to wrangle.

It’s odd though. I struggle to recommend them to people, even though they’re my favourites. I don’t like to push people into an experience that might feel horrible the first time round. It’s like asking someone to dive into a river that will be cold until they adjust.

But I want to talk about Carl Chudyk anyway. Once you’re swimming with him, you’ll find something you couldn’t get anywhere else. You’ll open tiny boxes and find yourself tucking ideas under possibilities and watching your table turn into a sea of systems. You’ll still be finding surprises on your hundredth play.

You’ll get stories. Stories of the time a game felt different to anything else.

These aren’t reviews. There’s no time for that.

Instead I’m going to dissect a few games, pull out a few gutsy details, and see if I can read in the entrails why Carl is the way he is. Why he fills me with wonder and what makes me scream. Take a deep breath. It’s a fast river, you might not be able to get out.

Red7 – Rules are made to be changed

[Co-designed with Chris Cieslik, who also helped to develop several of Carl’s other games.]

Red7 is one of his simplest games, and it comes with one central rule. At the end of your turn you must be winning. If you aren’t winning, you’ve already lost.

That sounds odd, but it makes sense when you’ve seen the rest.

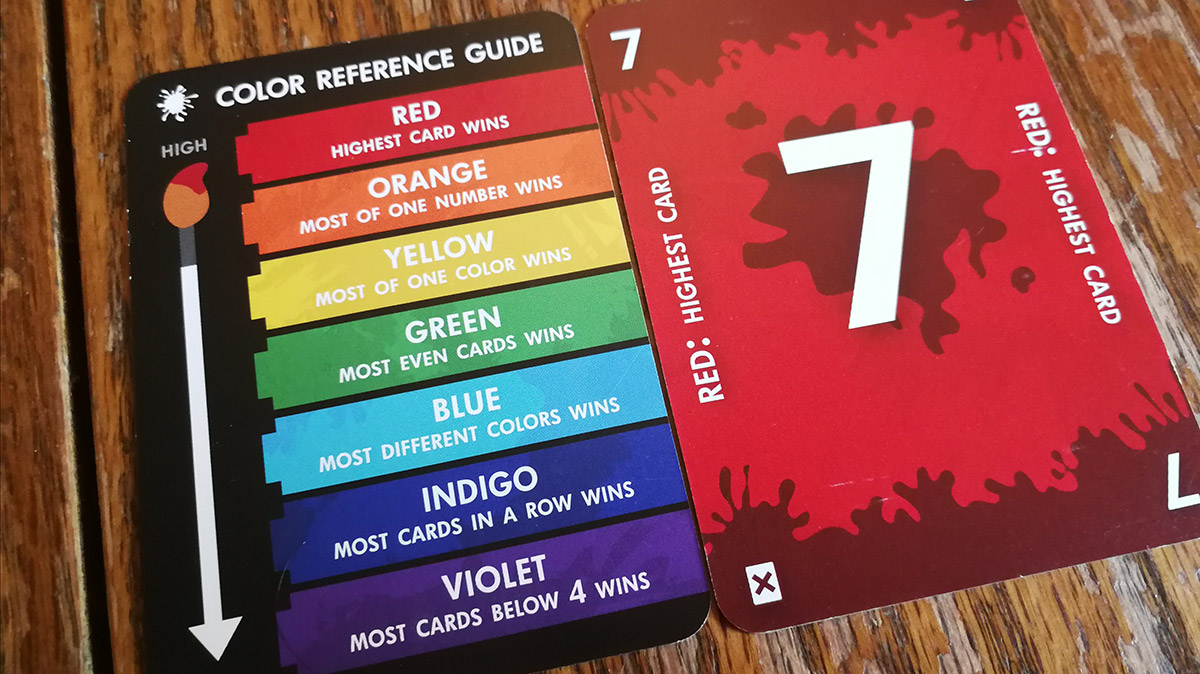

On your turn you can play a card in front of you, or play a card into the centre of the table, or both. The card in the centre dictates how the game is currently won. You might be looking for the highest number, or the biggest set of matching numbers, or the most cards of one colour. The cards in front of you get compared to everyone else’s, and you see if you’re winning.

If you can’t play a card on your turn, or you can’t be winning by the end of your turn, you’re out.

It’s simple, but it gives us a core concept from Chudyk’s games: The rules can change while you’re playing.

Red7 has a closed ruleset. There are seven suits, each giving a different win condition. You can see them on a reference card, all the different flavours of victory at once. But every turn the game can change. Within those seven orientations, you will be a winner every turn, until you aren’t. You’ve got to adapt as the rules change.

So each turn leaves you wrestling with the options in your hand. You can change the rules, or you can make yourself stronger, but you need to adapt, need to shift, need to plan, need to worry. The possibilities are all laid out clearly. But you need to find a way to win now, and stay winning. It’s a ruthless bucketful of maths and hope, and it’s a delight.

It’s the simplest implementation of his rule bending extravagance, but it’s got that beating Chudyk heart. Carl likes it when you play a card that breaks the game. It’s common to complain about overpowered combinations, game breaking possibilities. But for Carl that’s the goal. The game is made to be broken, or at least changed. You won’t often finish playing quite the same game you started.

Innovation – Tucked away complexity

This is a frustration, so it’s one we should be up front about. A lot of Chudyk games are hard to learn. You need to learn a specific language, a particular syntax. Remember how we said that rules are going to get broken? Well to do that you need to build up from a robust core. You need a precise vocabulary and a shared grammar, a knowledge of what can change, and what will stay the same. If lots can change, it’s harder to teach what stays the same.

The first time you play Innovation will feel cruel and random and ridiculous. To its credit, it is trying to cover the whole span of civilised life, and random and ridiculous is how history has always felt from the inside.

Innovation has a small deck of cards for each of ten historical eras, from the stone age to the information age. Initially, there is no way to win. You’re introduced to the concept of scoring, but before you can do that, you have to find the cards that let you do it.

Quinns’ review stopped short of recommending this tricky beast, but includes a lovely example of just how bewildering the opening moves of this game can feel.

This is infuriating for new players, but it’s the price of having a rich web of possibilities. Every card is unique, and many of them are explosively powerful. I’m still discovering cards that I giggle or goggle at when I see what they can do.

There’s a late game card called Fission, illustrated with a tiny mushroom cloud. It’s hard to activate, but if you do, you’ll remove nearly every card from the table. All those civilisations you built? They’ll crumble in a fiery instant. But you don’t stop playing, you carry on. It’s just that you’ve been bombed back to the stone age.

I can’t think of another example of a pun executed entirely in mechanical terms. I can’t think of a card in a game that has made me laugh so hard and feel so bleak.

There’s wonder and weirdness tucked away in those decks. Unexpected possibilities and huge swings in power. I’m always eager to play, because even after tens of games, I don’t know what will happen. When did a civ game last make you feel that way? Game after game after game, Chudyk dishes up the unexpected.

Glory to Rome – Everything I can do, you can do better

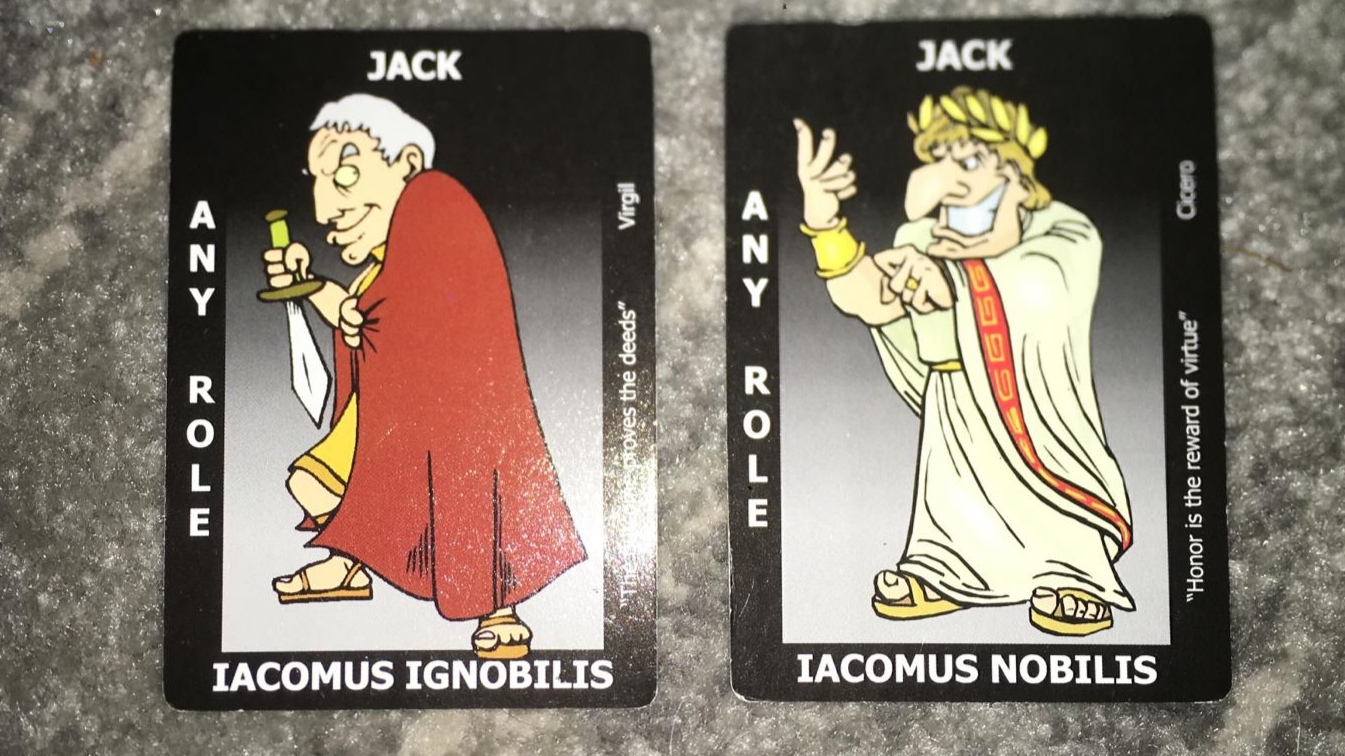

Glory to Rome is Chudyk’s ugly, out of print opus. Its enormous deck of cards is heaving with combos, game-breakers and weird ways to win.

It’s also got a baffling turn order ritual that emphasises another Chudykian obsession. When you do something, everyone else might get to do it too.

When you take your turn, you play a card in front of you, representing a citizen of Rome. Then wait to give everyone else a chance to follow. If they’ve been hanging around with the right people and have a matching card to discard, they get the action too.

It’s a nasty weight to put on a decision. You can’t just do something because it benefits you, you have to weigh up how much it will benefit everyone else. Are you willing to risk giving them a leg up? Do they have the card they need? You don’t know. But it begs you to look at other people’s plans, stay invested in their engines, so you can tell when you’re giving them a helping hand. It’s a simple, cruel question about your efficiency, and whether you’re making that action work harder than everyone else. It makes every turn count. Every opponent could be your saviour or curse with the right action at the right time.

Quinns would tell you that Race for the Galaxy was the pinnacle of this kind of ruthless hand-management, but I think it’s Carl who knows how to make you wrestle your own hands the hardest. And that’s mostly because he makes you worry about exactly how much you’re helping everyone else with that move. There’s a real fear to each decision, as you throw away something you can use and watch to see if anyone latches onto the opportunity and gets you in a headlock.

Does it make you feel like a glorious Roman? Does it take you from zero to hero to Nero? Honestly, it’s hard to say. Everything has the name of a Roman building on it, and occasionally you get to say ‘Rome demands stone’ and see if anyone coughs up with the aggressive legionary action. The art is more preschool than praetor, though. It’s hard to sound impressive when you’ve got a tiny MSpaint drawing of a semi-naked Roman in front of you. But there’s a sense of the bustling forum in everyone calling out as they try to make the most of your turn. Everyone staring pointedly at each other’s cards looking for a chink in your engine like jealous senators in March.

So many of Carl’s games have some mechanism by which your action will be borrowed by someone else. It keeps interaction high, keeps attention focussed. It’s smart, it’s weird, it’s frustrating and it’s clever.

It’s very, very Carl Chudyk.

Mottainai – Every little thing means five things

For me, Mottainai is Chudyk’s masterpiece. My application for this very job was a heartfelt pouring out of affection for this game recorded by the side of my favourite river. It’s a spiritual successor to Glory to Rome that borrows most of the rules, but puts the brakes on to make for a more meditative, more explorative experience.

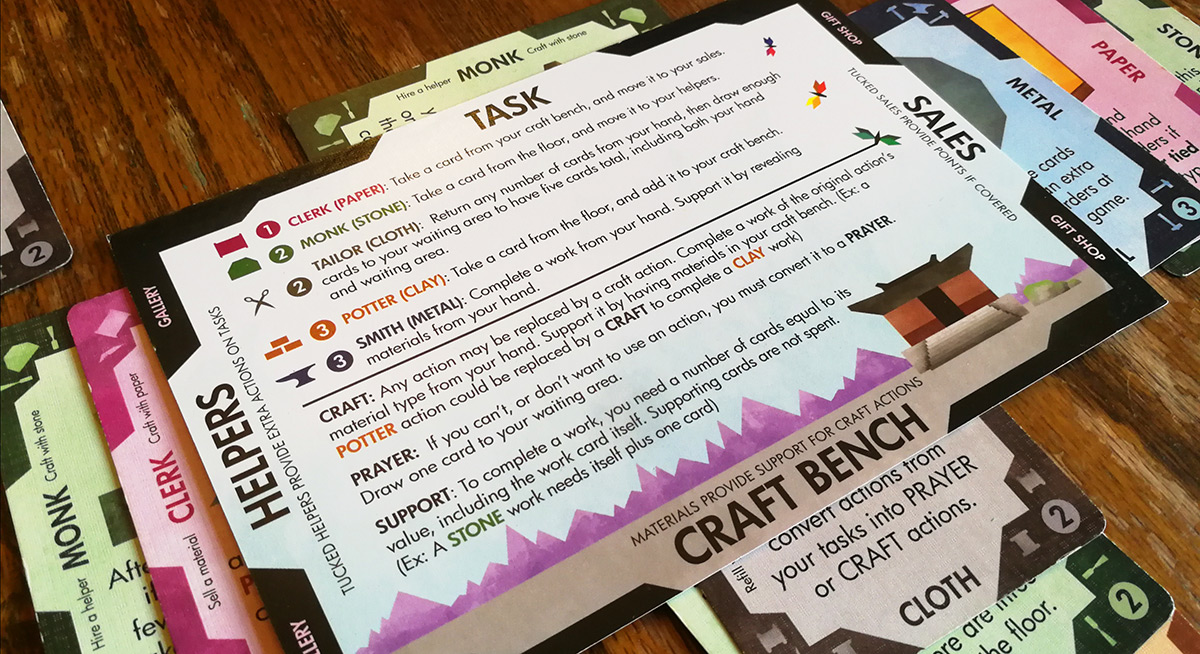

It shares with Glory to Rome Carl’s next kink, multi-use cards.

In Mottainai, you’re running a slightly capitalist Buddhist temple. Every card is an action you can take, grabbing new helpers as they pass by, moving materials into the crafts bench. Each card could also be a resource you can use for points or building, metal or cloth or clay or stone or paper. It’s also a person who might be able to help you out, boosting the right action, a visiting monk or a hard-working smith or a humble clerk. Or each card is a unique work, an object you can build for a game breaking effect. You’ll find everything from pin cushions to paper dolls, and each one can go in your gallery or your gift shop.

This makes every hand a puzzle. What do you need to hold on to? What do you want to discard so it’s available later? What do you want to use now? What do you want to save for later? What would you rather get rid of to make some space?

Now, add that list of questions to the fear of knowing that your opponents will perform any action you choose for yourself, and you’ve got to treat each hand, each turn, with precision and care. The word Mottainai translates literally as ‘everything little thing has a soul’ and more figuratively as ‘the regret experienced over wastefulness’. This sums it up. It’s a sweet, ruthless game of squeezing every last thing out of every hand, and delighting in the strange things you’ll make with it.

Mottainai’s theme doesn’t come from its slightly absurd take on monastery life, but on the meditative flow of play. It feels soft and gentle, even as you’re getting frustrated and being ruthless. It’s a game of exploration, of wonder, of mindfulness and movement.

Every little game has a soul.

Impulse – Over-powered is the new normal

If Innovation was a playful homage to civilisation games, Impulse is a full on satire of 4X space games. It’s a disco opera take on Star Wars, in the best possible way.

Impulse finds yet another use for the cards you play with, as a galactic map laid out in the centre of the table. You’ll be sending fighters and transports across great voids, looking for planets that are just like the cards in your hand. You go through a rigmarole of different actions every turn, and every one of them can cascade into others.

You see that map on the table? They are still cards, they’re still actions like the ones in your hands. If you can land transports on a planet, you get to take that action. I’ve seen turns where people bounce around half the galaxy in a turn, picking up and pushing about, and desperately trying to find the thing that gets them what they need. You don’t just take each other player’s action. You get to repeat any combos on the table that anyone else has uncovered, provided you’ve got the fighters to back up your boldness. There’s a whole astro-geography of possibilities laid out in between everyone, a shared puzzle for you to fight over.

The cards themselves aren’t as wild as Innovation’s bizarre deck of possibilities, but in Innovation you only do one thing at a time. Here you’re trying to find a way to do twelve things a turn, and sometimes it’s even possible.

Combat is vicious, board states exploitable and absolutely everything is ridiculous. It feels like a monster of a game. It’s only an hour or so to play, but squeezes all but the most diplomatic dramas of Twilight Imperium, into these sharp, overpowered bursts of movement, combat and domination.

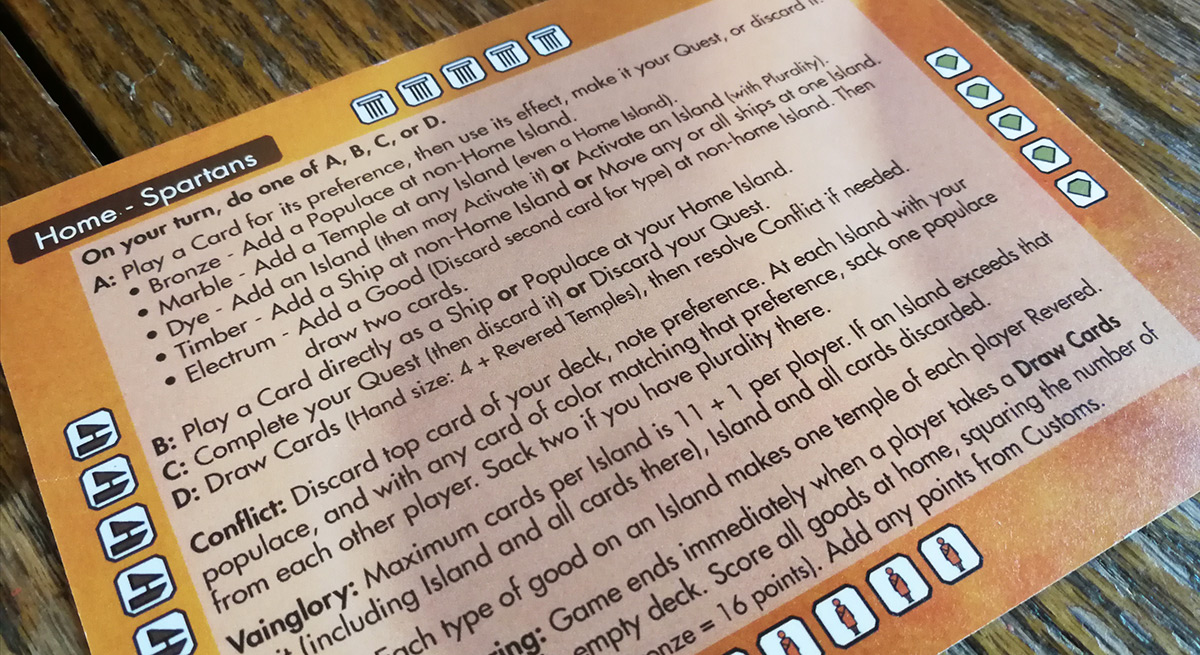

Aegean Sea – Put it all together

I’ve only had a brief shot at an early prototype of Aegean Sea, Carl’s next big thing, but I can see something that learns all of these lessons and twists them into a new shape. An island hopping wargame where each island can be home to five flavours of cards and the potential for huge conflict and game-breaking possibilities.

Expanding on the passion for unique powers, each player has their own entirely unique set of cards to draw from. Digging through your deck to find the right tool to manipulate the cardboard sea into something you can win from is a confusing, thrilling nightmare. Islands can be destroyed by the gods for their hubris, and absolutely nothing is safe. Your home port can be invaded by opponents, and the points you’ve earned can be taken from right under your nose.

I’ve no idea if it’s going to be tight and taut enough to bring Carl to the masses, but I’m excited to see how it plays out. And because it’s Carl, I don’t even mean how the prototype evolves, I mean how different each game could be.

FlowerFall – Let’s just ignore all of that

Of course, everyone’s got a real outlier, and for Carl, it’s this very particular area control game. FlowerFall features cards being dropped from a height to create a randomly scattered meadow. It’s simple, it’s silly, it’s nothing like anything else. It’s got comedy and tragedy, and rules that you can learn in a heartbeat.

On your turn you drop cards onto table, and they land where they land, creating new flower-beds and covering over others. Have the most flowers visible in a chain of green, and you win points for each green flower still visible on that patch. That’s everything.

It’s not got the depth of anything else we’ve talked about, but it’s still utterly unlike anything else out there, and I love him for doing it.

* * *

That’s just the highlights of Carl’s acclaimed and continuing career making games that nobody else really could. Games that you’ll want to play again and again, that unfold in a new way every time. I think he’s wonderful, I think he’s playful, I think he’s obsessive and I think he’s one of a kind.

Carl Chudyk is my favourite designer, even though when I’m teaching his games I feel like I’ve turned into a parody of a constitutional lawyer. I find myself using oddly specific turns of phrases and getting excited about incredibly finicky details. The games fill me with joy, though. They surprise and excite me. I love watching the rules and the cards click with people, watching them realise just how much could change, how quickly tables can turn.

I said this wasn’t a review, but I would also vouch for any of these games. If your interest is piqued, and you don’t mind an inconvenient initial headache, I think you’ll find a wealth of weirdness and fun.

Let me know who you think I should dive deep into next. And if you end up trying out some Carl Chudyk, let me know how it goes.