[Our own Leigh Alexander has been learning Netrunner, which we reviewed here. She found the experience pretty important, and we arrived at this. A long collaborative feature, with comments from Quinns and art from Jesse Turner. Enjoy, everybody.]

Leigh: “I can’t,” I say, and my voice sounds small and far away.

“Yes, you can,” says Quinns across the table. “Just think. You just have to stay calm.”

I have to stay calm, I think, but my body revolts. My guts secede, and warm fingers of shame crawl up my cheeks. Panic knocks gently but insistently at my breastbone. “I can’t,” I say, and it feels true. “I just can’t.”

“Look,” he says, gently. “You can get through this.”

“How,” I say, and there is a genuine tremor, an unhinged note I hear in my own voice and it makes me even angrier.

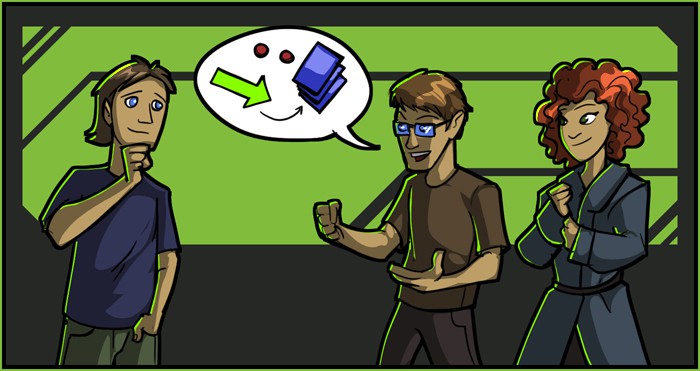

He says: “Listen, Leigh. This is a strength four piece of ice, and you have a token on Crypsis, so it costs you four to bring it up to strength, and one for each subroutine. There are two subroutines, and you have seven credits, and you can also use your Datasucker tokens and one Bad Publicity–”

I can’t. I mean, it’s just a goddamn card game, but this is the part where I get up and leave the room, and slip into my bedroom. There is a perfectly reasonable part of me that is trying to process information. Oh kay. You just got a bit frustrated. It’s a complicated game. Shake it off.

The other part of me wants to fling myself bodily across the bed and cry like a child, hiding among Ikea furniture and the ghostly shapes of unwashed clothes. Ridiculous.

Aaand, oops. That’s the part that wins.

Quinns: Some background: Leigh may, or may not be, dyscalculic. And while I find teaching games easy, she didn’t just want me to teach her Netrunner. She wanted to join in, and join her friends down the rabbit hole of Netrunner being a hobby. I don’t think she was jealous, listening to her friends chat endlessly about the game’s electric ecosystem of monthly card releases. It was something else.

All of this wouldn’t only be a challenge for her. I’ve written before about the emotional and intensely personal aspect of table games.

Imagine being able to reduce your friend to tears with the flipping of one card. For whole weeks, every other game of Netrunner we played required a post-mortem where I told Leigh what she’d Done Wrong, and when that was a little too much, where I’d try and stop for the night. Which was never easy.

“AGAIN,” she shout, already resetting the table after a game. Wiping her servers clean, wiping her eyes clean. Disassembling her runner’s rig.

It seems such a cliche in kung-fu flicks when the master tells the pupil, so clouded with emotions, to stop because they “Won’t learn anything else tonight.” I was surprised to find myself saying it. I was also surprised to find that it hurts both of you. It’s a terrible thing to tell anybody that they cannot learn.

“We’re done for today,” I would say. “Let’s go again tomorrow.”

Leigh: “Best” is a word I have tried uncomfortably to hold hands with ever since I was a child, when I show-horsed, willingly and with aplomb, through a sequence of auditions and competitions and performances.

These were sometimes overt and sometimes private, the difference between supposing myself ‘at war’ with a rival little girl for the role of Tinkerbell (I won), and wrestling parts of myself in front of the bathroom mirror — wrenching a barrel brush through my unruly hair, pinching inches, sucking in my breath until I felt lightheaded (triumph not assured). Years running myself ragged on treadmills, figurative and actual, to nowhere (net loss, if we’re being honest).

I guess it makes sense that I came to work in games as an adult. Our culture is defined by trials of fire. We worship at the altars of obsessiveness, skillfulness, competition. Leaderboards. Every time I post an article, someone Tweets to me that it is the best article, that I am the best, and we use the word best so often that it stops meaning very much. Every year we games writers make best-of lists. The categories are multitudinous. We are jurying constantly to find the best, and like demanding parents we don’t really think about whether our young and nuanced medium benefits from the strain of our expectations.

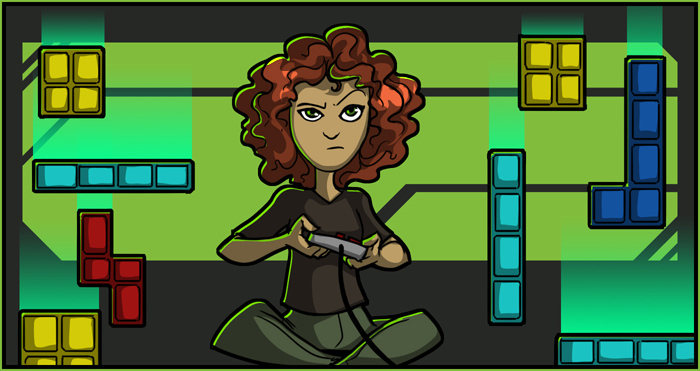

I don’t like to play new games in front of people. I want to learn them first. My memories of falling in love with the medium are of a private congress, sitting in the dark, in a silent meditation with a screen. Worshipping at a square of light, eyes aching past bedtime. When young I could play Tetris for hours, sorting tumbling chaos into tidy lines, watching them disappear.

I have groomed characters, finished sidequests, obsessively filled out skill trees. I am a completist. I put things in order. I increase statistics. I accrue a set of skills logically and then I use them to defeat circumstance, chaos. I hold a controller, because I need to be in control.

I have always feared losing. To be seen to be struggling — to experience frustration, to have to say, numb in the face of overwhelming information, things like “I don’t get it” — disrupts me bodily, disassembles my composition. Even the prospect of failure is humiliating. I can do anything, I am good at everything except for all the things I am not good at, and I’ve always managed to avoid those things as if they carried germs.

I’d been making fun of Netrunner for a long time before I asked Quinns to teach it to me. It’s nerdy, this big card game full of numbers, events, assets, resources, data packs, that kind of thing. I mean, I’m in video games, and I think it’s nerdy.

In the game of Netrunner, one person plays as a corporation, “the Corp,” and the other plays as a hacker, “the Runner,” trying to dismantle the corp by stealing its secret plans, its “Agendas.” People build one corp deck and one runner deck, and there are four different corporations you can play as and three classes of runners (anarchists, criminals, the programmer elite), and there are different characters and styles within all these factions.

The runner installs programs — sets out cards — that augment the behavior of “running on” the corporation’s cards, its “servers”. Corporations can protect their servers by laying out “ICE” cards horizontally in front of them. The runner has to break the ice.

I am immediately drawn to the theme: Cyberpunk dystopia. Pictures of hackers in neon sunglasses plugging tendrils into their spines and communing with lucite radials or monoliths of light. That 1990s vibe I can’t get enough of, like, ever (my sister says I’m “trapped”). Like peeking through a keyhole, like seeing a light at the end of a tunnel, I understand that Netrunner should be fun, can be fun for me. But everything in the game has a cost. Everything involves a calculation. Sometimes many.

I am bad at this. Oh my god, I am so bad at this. Sometimes my synapses flood and my ears burn and I feel like I might be sick. I cry. I’m not exaggerating.

“It’s nerdy” is a good reason not to try a lot of things, especially if they scare you.

Here is a thing about games: They write you and rewrite you, like the flecked arm of a dot-matrix printer, inking your image in one stroke after another, there to be read. People love Dark Souls because it helps us answer a question about ourselves: What are we made of, if everything is bleak and futile? Finishing that game is more than just finishing a game: It’s proving to ourselves we have what it takes to whittle down, claw away, gnaw to the marrow of futility and surpass it. Once you’ve learned that, you can’t unlearn it. You’ve changed.

So I guess what happened is I took a look at this huge slate-gray box belonging to Quinns, that said ANDROID: NETRUNNER on it, and had pictures of a Blade Runner-esque cyber dystopia on it, and was full of cards studded with unknowable numbers and etched in phrases like “your maximum hand size is equal to the number of credits in your credit pool” and “hosted power counter: give the runner 1 tag” and for whatever reason I thought: Maybe this game will change me.

“Teach it to me,” I demanded of Quinns one night, hanging languidly off his living room sofa.

“I really don’t think you’ll like it,” he said, probably a little warily. My lips must’ve been black with wine.

Lately he had invited me to try some local multiplayer PC game with him, and I hadn’t taken to it right away. I’d felt slightly clumsier at it than him, and when he attained the first of many objectives before me I gave up. “I hate this game,” I’d said. I had played for about thirty seconds.

“Netrunner is… it’s pretty mathsy,” he warned me.

“I don’t care, I can do it,” I said. “I can do anything.”

Three days later I’d be crying in my room, wondering what was happening to me, and feeling very much like I was not an adult.

Quinns: It was only a month later that things got difficult. In one of the most fascinating experiences in my gaming career, we were having to work through the game on an emotional level. We discovered her games meant so much to her that Leigh would tilt.

Tilting is a term from gambling, where your play collapses when you start losing. Imagine you’re in the lead in a poker game, and in a single round another player rips half your chips away. This isn’t just a rabbit punch to your confidence. A great loss sees players having to adjust to a dramatically different game state, while struggling with the adrenaline dump in their bloodstream, and ignoring the alarm bell in your head that WHAT YOU’RE DOING ISN’T WORKING, because it’ll only ever lead you in the wrong direction.

At best, tilting sees players losing tempo to their opponent, as they work to not lose as opposed to playing to win. At worst, tilting leads to panic, which leads to further punishment as the player tilts further and further off-centre.

There were other knots in her play for us to untie. Again, because the game meant so much to her, we began discussing whether she was too aggressive, and hunting for agenda cards when she should have been building.

Working through this murky territory, I was grateful to be past the aspect of teaching that I found most uncomfortable- the question of how hard or soft I should be in our play. Come at your friend too hard, and you’re just going to make them discouraged. Go too easy, and the games are meaningless.

“I WON!” Leigh would shout, in those early days. And it’s a funny thing to smile bashfully, and nod, with that brittle truth stuck in your throat- “I was going easy on you.” You don’t have to say it. Bits of it will be stuck to whatever you say next.

But she was getting better every week. By January, I wasn’t going easy on her anymore. I was playing as hard as I could.

Leigh: Try on this definition of “mature” and see what you think of it: Maturity means running toward new things, to see what you can learn, where before you ran away from them. That’s one of the tricky little itches video games have always scratched for me: You have no option except to move forward.

Whether or not you know what is coming you have to be prepared, your finger on the trigger, at max level, the right equipment, your reflexes primed. I remember during the awkward adolescence of games in 3D polygons, oddly-placed fixed cameras almost frightened me. I had no control over how much of the future I could see.

It was Netrunner that crystallized for me the uncomfortable fact that in real life I’ve always run away from any space I couldn’t see completely, from any challenge I might not be able to win, and from any situation where I struggled to succeed.

At a Christmas party with friends everyone is surprised I’ve taken up dorky, mathsy cards. When I first moved to London someone I met said I “looked trendy” and that is not a compliment here. Clinging to my drink, I explain that I’m “hacking my personality” (whiskey laugh) through Netrunner.

“No, really,” I say. “It’s totally good for me. It’s the first time I’ve ever applied myself to something that’s so, like, antithetical to my interests. I have, like, so few of the skills it takes to be good at it that I figured it had to be good for me. I want to learn not to freak out when I’m losing, and to work hard at things even if they grind me down.”

I explain about my perfectionistic childhood and the weird self-directed learning program I attended as a child, where I’d pitch tantrums to avoid having to learn math, which I hated, especially long division. “I’m not sure if it came so hard because I have an undiagnosed learning disability to do with numbers – I mean, I still count on my fingers as an adult,” I say, “or whether I just learned early on to try to stay away from anything that made me feel stupid.”

People nod attentively, even warmly, and I feel uncommonly vulnerable, paranoid. I know nice people. I’m pretty sure none of them think I’m ridiculous. But even knowing this a wild panic crawls along my scalp. Even talking about the part of me that unravels when faced with the challenge of newness, of inability, triggers a fear of looking ridiculous.

And Netrunner is pretty ridiculous. You sort of have to be the kind of person who admits to attentively watching all three Matrix films to fully appreciate it, and no one wants to admit that. One of the best things about the game is how its theme and mechanics knit so beautifully. Are you the kind of hacker who stays up all night making connections at an underground nightclub, shoots a dangerous stimulant and then runs, screaming madness, toward glory or death? The kind with a workbench full of disassembled console guts?

What’s your corporation’s thing? Wall street filthy money, omnipresent surveillance, stone-cold bioengineering? Do you have weird friends who chat to babes all day, are you a conman who makes money recycling crummy last-gen iPads? Will the corporation level your entire neighborhood, your home with you in it, in a scorched-earth “redevelopment” plan? For all of Netrunner’s numbers and clauses, it lets you answer those questions. There’s a lovely symmetry to its storytelling that’s been absent for me from other card games, which present mainly as a grid of Tolkien-esque gibberish.

This is a lexicon that can be mastered. Once you learn it, you find yourself having unbelievable conversations — you did a Demolition Run with six tokens on your installed Medium. You learn that Pawns are the only Caissas that can be installed on Scheherezade. You shut a runner out of your remote server with an infuriating little pop-up window.

I found myself telling friends who run the Terminal7 Netrunner podcast that I Psychographics’d an Ice Wall and they laugh because they’ve never heard that one before. I can speak the language. It’s language. Oh my god, I’m actually getting it.

I can win. I can win. I can win. I start winning.

Quinns: In the dank basement of a London pub, Leigh and I are playing Netrunner with a big group of our friends. Individuals for whom playing Netrunner wasn’t some life-changing decision, who never once collapsed into despair because they misread a card. In the dim light, Leigh is walking from table to table, sometimes laughing, mostly taking scalps. She wins. She wins. She wins again.

We step out into the night, puzzled by cheap lager, victorious. It’s a thrill that lasts for about five minutes.

“I’m going to take the Marked Accounts out of my deck,” Leigh says. “They’re not working for me.”

And that was it. Chatting and ducking through sodium-coloured Soho alleyways, we’d arrived. This was never about winning games. The reward of taking any game seriously is to be connected, as if by underground wires, to humans all over the world. To have access to a private language, to enjoy another way of bonding with your friends and family. Play is just as important to adults as it is to children. Like everything else in life, it just becomes trickier as you get older.

When we go back to the pub the very next week, it’s packed. We’re playing cards shoulder-to-shoulder with strangers who have no idea what Netrunner is. It’s a great feeling to have a hobby that looks so bizarre, yet to have so much fun that onlookers become jealous. Like you’ve jinked outside the stream of what’s allowed by society. That feels like winning for real.

A few beers deep, a man next to me asks what we’re playing. I give him my practiced micro-pitch: “It’s a bit like Magic: The Gathering, but better.”

We chat for a while. Eventually, half to nobody in particular, half into his beer, he says: “I wish I had a hobby like that.”

And all I can think is, yes. I bet you do.

—

Leigh: I thought my Netrunner story would end up being about how I took my fear of loss, of clumsiness and my ease of overwhelm and found a way to win. How I learned to tolerate failure and frustration, and how that greater tolerance made me a true competitor, rather than an avoidant little bluff artist. I thought I’d offer lessons, like if math forbids you, try thinking of it as language.

I thought I’d close with the news that I entered my first Netrunner tournament. Or with the story of the first time I defeated my teacher, like really won without him going easy on me, and how I almost fell out of my chair, adrenaline-flooded and nauseated and excited, as I scored the last Agenda and he smiled and said, so gently, “you did it.”

But instead, I’m going to say that I still lose a lot. And the brilliant thing about Netrunner is that everybody, everybody loses a lot. That no matter how good you are, half the time you can head out to play with some friends and lose every single one of your games. You teach somebody Netrunner, and in their first practice game, they beat you. That happens all the time.

It’s not about mastery, it’s about constant tinkering and experimentation. Sometimes luck is not on your side. Other times you sit down with a new group of people and find their local metagame is about completely different strategies than yours. Just seeing the game in a new light can change the way you play.

You build a deck, a wild risk, and it works, and it’s amazing — and then it doesn’t, really, not over the long term. You collapse, laughing, and build something else. You talk about it. It’s addicting to talk about it. People like to play Netrunner so they can learn about it. People like to lose Netrunner so they can learn about it, even though it can be occasionally heartbreaking to be destroyed.

Getting your head around Netrunner is like trying to grab a fish in a river. It slips always just out of your reach, lets you seize it only for a moment. And just when you think you’ve really got it, brand-new cards are released, making new mechanics possible. It is not about the climb to dominance. It is not about getting better and better until you’re impervious. It’s not about winning, but about growing, laterally, like you’re sketching a map of a world that will never be finished being born.

I fell in love with this game because becoming good at it, and having fun at it, and making it mine, meant that winning stopped mattering at all. And that there was less space to be afraid. One time I was playing with a friend at a party and noticed that it had been quite a long time since I’d had a glass of wine and that I didn’t really want one.

I’ve become someone who gets up early on a Sunday, zips up her heeled booties, picks her hair out and goes to a board game shop to play cards. I’m the girl shuffling her deck in the corner of the pub downstairs on some Thursday night, buying a round for the friend I’m going to play against next.

That’s what’s best of all: I surprised myself. Through a game, I can become someone I never thought I could be. I can do something I never thought I’d be able to do. It’s not only that I can play Netrunner, and that I can sometimes win. It’s that I can lose.

A drunk guy in the bar wants to know what we’re doing, and I can tell he is making fun of us nerds. I shut him down with a big white grin, a hip-switch and a heel-click. I still expect to win at some things, of course.

[Leigh Alexander is a gaming and culture writer whose work is found most easily in the cheery roundups on her site. She is the author of Breathing Machine, a stormy memoir of growing up in the earliest days of the internet.]

[Jesse Turner is an artist working primarily in video games, currently breathing life into the awesome-looking Viking Squad and the still-more-awesome-looking Crypt of the NecroDancer. Adventure Time fans might be interested in or horrified by his swank range of t-shirts and sweaters.]

[Quinns? He just lives here.]