Paul: Oh my word. I have had A Hot Time in Texas and, boy oh boy, I can’t wait to tell you all about it. Do you want to know all about BoardGameGeek Con 2016? Are you settled and ready? Are you prepar- I DON’T CARE LET’S GO. The starter pistol has fired so LET’S TALK ABOUT FLAMME ROUGE.

Every year that I go to BGGCon there’s always at least one game that I’ve never heard of and yet everyone is talking about and desperate to play. This year, Flamme Rouge was that game, speeding from table to table until every other person at the convention had the warm odour of sweaty French cyclists sliding up their nostrils.

Flamme Rouge is all about cards and bikes. You have a winding track, marked with inclines and declines, plus two cyclists each that are represented by a deck of cards. Each card tells you how many spaces a cyclist can cycle their cycle in a turn and you draw four of these, playing (and thus discarding) one of them, putting the rest back in your deck. Maybe you cycle nine spaces! Maybe you cycle three. The thing is, it’s not really about how fast you travel, it’s where you end up.

If you can time your pedalling correctly and, say, fall in behind one space behind another rider, you can slipstream forward for free. If you end your turn on a downward gradient, you’re guaranteed a minimum number of moves next time, meaning you have a chance to burn a crappy card. Surge ahead by yourself, away from the comfort of slipstreams, and you have to add an exhaustion card, which gives you a crappy two space move, into your deck. You’ll see that sooner than you think, too, because the decks are small and you, ahem, cycle them very quickly.

Not only is Flamme Rouge a game that plays as fast as its subject, it’s also pretty damn good. You’re immediately trying to suss out how hard other players are going to cycle, seeing how you can weave through the pack to enjoy that slipstreaming, and combining both your cyclists to this effect, or just to try to block the road ahead, is surprisingly tactical for a relatively simple game. It reminds me a little of K2, with cards representing movement and two figures on the board that you can use to support one another. Oh, and the track pieces are all double-sided can be reassembled in any way that you choose. It’s tour de tastic! This year, Paul’s Best Game About Bikes Award goes to Flamme Rouge! Please clap.

I don’t know what “tour de tastic” means but NEVER MIND. Another wonderful surprise of the con was Honshu, ostensibly a card game but really a tile-laying game about trying to make The Best Possible Town. If you know me, you know tile-laying is kind of like crack cocaine for me, insofar as I insist I don’t have a problem while simultaneously begging people, wide-eyed, to give me just one more game. Let me tell you, Honshu was THE GOOD STUFF.

Your cards are all wee two-by-three blocks made up of things like forests, lakes, factories or houses and, each turn, you choose one from your hand to lay down in front of you. Each card has a unique value and whoever played the highest gets first pick of all the cards laid out, claiming it and then adding to an ever-growing tableau, but slotting at least one of its blocks underneath another card. Turn order is also changed by the value of the card you choose, meaning that you’re constantly conflicted by wanting to play something that might improve your city, but also wanting to play a high value to keep yourself at the top of the pecking order and steal away any cool surprises that other players reveal.

You’re aiming to score smokin’ points by building a huge, contiguous town out of all your cards, as well as winning bonuses for forests, for creating big lakes and for finding room for special features that create and demand resources. If you can end the game with, say, a couple of lakes and mines that produce blue and grey cubes, along with civic utilities that demand those cubes, you’ll earn extra points. Except you can also sacrifice those cubes to increase the value of the cards you play and improve your chance of staying at the top of the turn order. Is it worth it? It might be, since you’re constantly aware of the other towns that everyone is constructing and there’s always a balance between grabbing the cards that help you the most and denying other players something that would help them.

BGGCon often has excellent surprises that you discover aren’t yet available where you live (two years ago, everyone was excited about the then rare Spyfall and Mysterium, which used much of the momentum of that excitement to find distributors), and many of us North Americans were sad to hear that Honshu wasn’t easy to get on our continent. Until we heard that it soon would be! Hooray! Thanks, Renegade Games! Honshu, please accept Paul’s Best Card Game of the Con Award.

From the uncomplicated towns of Honshu I took a bullet train to the very core of the forthcoming New Angeles and, oh my God, this is something else. Fantasy Flight’s return to the Android universe (the home of Netrunner) has everyone playing cynical, scheming corporations that control the fate of this far future megacity. Between you, you must keep the city functioning and tackle the constant unrest, riots and power outages, each of you suggesting political proposals that ostensibly improve the situation, but also increase your own prestige. One player’s hidden identity may or may not be that of the Federalist, the person who wants it all to come crashing down, but the rest of you are all trying to keep things in check and frequently must put the city’s need before your own ambitions.

I’ll tell you what: it ain’t quick. The box suggests a two to four hour play time and, with six of us, I have to admit that we didn’t finish our game. After three hours, and most of the way through, we’d spent a lot of time playing cards that proposed various economic, political or plain old authoritarian solutions to whatever things had gone wrong that turn. Counter-offers were proposed and debated, all of us arguing (truthfully or not) about how these would keep us safe or make us more successful, all the time sat on our own secret objectives.

Life in New Angeles is one pugilistic problem after another, and a solution to one situation, such as rioting, might affect something else we had to monitor, such as supply and demand. New Angeles is about hashing out every decision, debating and pushing every possibility, and while I liked political manoeuvring, gentle persuasion and brokering deals, this constant conflict is going to exhaust some players. Learning the game’s many, many cards will also take a few games, since New Angeles has that very Fantasy Flight thing going on where the playing of a long-held card or the reveal of a secret objective can be very significant. Every shrewd politician needs to know the possible ramifications of their decisions.

I’m currently on the fence about this one, but New Angeles does receive Paul’s Game He Least Wants to Play Way Into The Night Award.

Rising Sun, Eric Lang’s spiritual sequel to Blood Rage, saw the light of day in a personally-presented and papery, pre-printing form (sadly not yet sexy enough to warrant a lot of pictures) and it immediately called to mind that increasingly popular vein of card-driven wargames where direct military conflict is only part of what leads you to success. Yep, I’m talking about cousins like Inis and Cry Havoc, games where map control and choosing your battles matters a lot more than just throwing a larger number of troops at your opponent.

Set in a fantasy-tinged version of feudal Japan, Rising Sun emphasises negotiation as much as conflict and, as you compete to be the most glorious of your peers, you have to consider not only how wealthy or how violent a clan you can lead, but also how honourable it is. Your clan’s honour determines the game’s turn order and, critically, acts as a tie-breaker in a game where the difference between success and failure can be very tight indeed. Battles are decided by secretly allocating resources to different actions beforehand, actions such as trying to defeat or capture your opponent’s troops, and in feudal Japan it seems it can be just as glorious and honourable to have your forces commit en masse ritual suicide as it is to have them fight. Wait, you can kill your own troops for points? Yes. Yes you can.

You might well have guessed that combining politics and honour leads to some interesting conundrums, too. While other games of negotiation and diplomacy might encourage timely treachery or opportunistic backstabbing, the substantial honour hit here makes such actions terribly, terribly costly. That’s not to say you can’t or shouldn’t be a jerk now and then, but you find yourself wondering if employing ninja in your next stratagem is worth the dishonour. The first impressions of Rising Sun suggest a game a lot more thoughtful and deliberate than Blood Rage, relying less on card drafting and more on both discussion and very, very careful deception. I present it with the Paul’s Game He is Most Curious About and Keen to See Again Award.

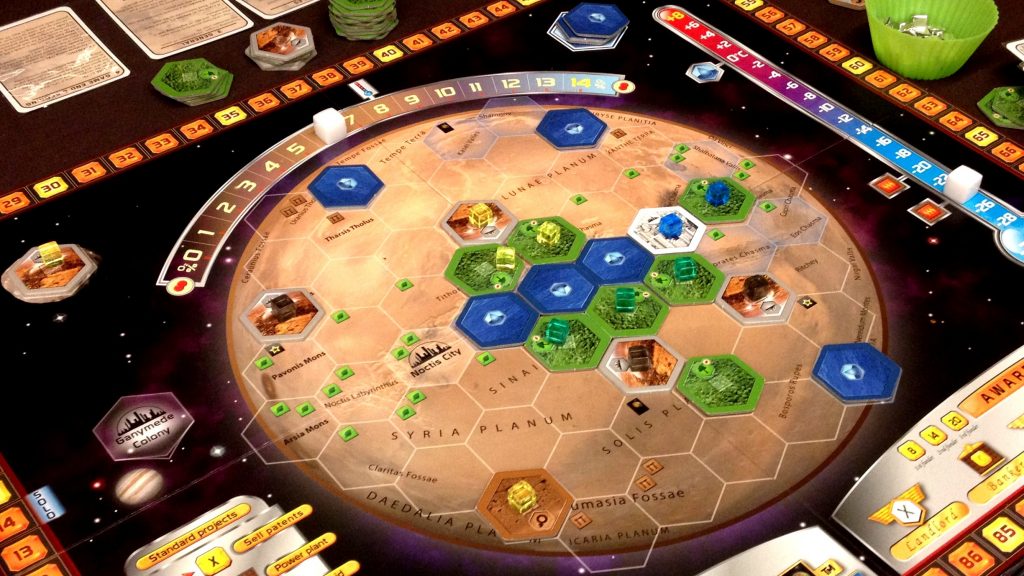

Terraforming Mars was also generating a lot of buzz and so I made sure to Rocketman my way over there one afternoon to find myself confronted by huge stacks of cards, hex tiles and shining, futuristic cubes. Was I out of my depth? Could I survive on Mars? Would I be a melodic, masterful Rocketman, like Elton John, or would I stumble around with a hole in my suit like a poop-fed Matt Damon? Neither, it turns out. I was more of the warbling mess of William Shatner. Just as I always have been.

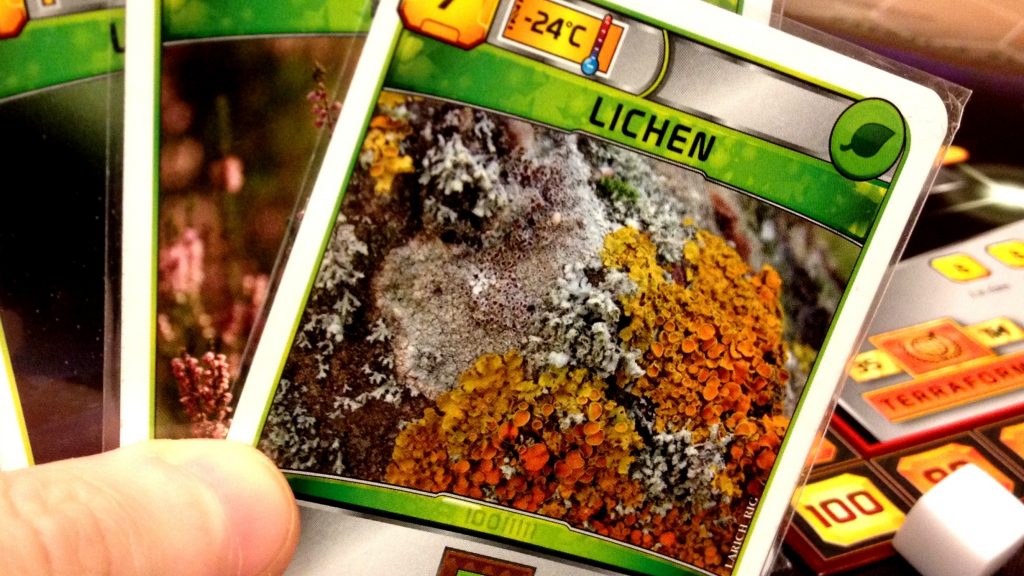

Mars ain’t the kind of place to raise a kid, since it’s too dry, too cold and too airless to begin with, but as you and your fellow players slowly gather resources, build power networks and found cities, it gradually becomes warmer and safer. A huge stack of cards presents all sorts of possible constructions and investments, but budgeting is tight and you’ll only ever be able to afford afford one or two each turn. Furthermore, there’s a lot of dependencies going on. Do you want to introduce fish to Mars, or start growing certain plants? It might still be too cold and you soon realise that to make progress it’s often as important to improve Mars in some way as it is to improve your own economic engine. Better found another city or smear another hex with some moss.

Oh boy, there’s so much moss in this game, so many cards that let you put some lichen on some rocks, and it’s here I have an admission to make: I found Terraforming Mars just too funny. We were constantly drawing cards that had another type of moss on them and, because we played a variant that had us drafting cards back and forth, laughing at what we passed on next. Y’see, the card art was a strange mix of well-designed pictures, questionable photography and cartoonish drawings. One moment I’m looking at a painting of an asteroid, then suddenly I have a bizarrely undramatic, unthematic photo of a dog or even a dust cover. I am not excited about investing in dust covers. Why does the future have people holding giant cardboard cheques? Why is my team of hackers a collection of exclusively Asian men who seem to be at a LAN party? Is the future economy based around Starcraft? Wait a second, I CAN PUT BEARS ON MARS.

I enjoyed changing the face of Mars, hex by hex, turn by turn, but of the con’s most talked-about games, it was also my least favourite and not one I feel I want to play again. Apart from claiming hexes before other players, through things founding new cities or forming new lakes, I was hardly ever doing anything that directly interacted with anyone else. Our own economies remained closed systems and while it was great watching a planet transform through our collective actions, I felt like we were individual spectators rather than interacting players. If we hadn’t chosen to draft cards back and forth, we’d barely have needed to speak to or even acknowledge each other. This game may be the ultimate in multiplayer solitaire. Still, it does win the Paul’s Best Game With Bears and Alarmingly Variable Card Art That Everyone Seems to Love But I Don’t Award, a category that’s always hotly contested.

With that multiplayer solitaire criticism in mind, I’m going to sound like a complete hypocrite when I tell you about my best experience of the con, something that was also mostly exclusive experiences, yet was also glorious in its scope: A Feast for Odin.

More like A BEAST FOR ODIN, am I right? This game is huge. It is absolutely huge, coming in a box as deep as a swimming pool that’s packed with hundreds… no, thousands? Surely thousands of small cards, wooden pieces, cardboard tokens and viking meeples. It. Is. A. Monster. And, like all monsters, I was terrified to face it.

Yet this is not the savage beast you might think. While, yes, the box is deep, Feast of Odin is broad, a game with a lot of scope, giving you plenty of things to do but avoiding making any of them very complicated. It puts you in charge of a growing clan of vikings who, initially, don’t have much more than a drinking horn to their name, but by the end of the game you’ll have them building great halls, whaling in the freezing seas and exploring distant lands. There is just so, so much for your vikings to do that you likely won’t be able to try it all in your first game, but you’ll be surprised how much you understand it all.

You begin with a few vikings. These vikings are doing nothing at all except standing around and counting their braids, so you send them off to claim spots on a board of different viking actions, such as chopping down trees, crafting treasures or piling into a longboat for a hearty evening of pillaging and plunder. There are something like sixty different things that your vikings might be able to do (sixty, by Thor’s hairy arse, SIXTY) and more complex tasks require more than one viking. Your choice is always whether you want to do a lot of simple things or fewer, more involved activities.

Yep, you probably recognise the sort of worker placement that’s typical of its designer, Uwe Rosenberg, but suddenly, all these interlocking systems start to grind together like cogs in a clock. Y’see, first of all, you need to feed your vikings. They harvest some food themselves, but it’s never enough, so gathering more is vital, not least because you get one more viking each turn and vikings are HUNGRY PEOPLE. But then you also have to keep expanding your territory, filling out the player board that represents your homestead. The best way to do this is by making things, buying or crafting items that you drop onto the board in a Patchwork or Cottage Garden-style puzzle. If you can lay them well, surrounding but not covering certain bonuses, then you earn yourself extra resources.

Except crafting resources takes time. You can upgrade animal products, for example, but is it wiser to have leather and wool to wear, or beef and mutton to eat? Do you send several vikings separately foraging, or put them together on a ship to chase a whale? If you have too many mouths to feed, you can send vikings away to form new colonies, but building ships also takes time and resources and another consideration is the importance of expanding your homestead. This, plus any houses you build or extra lands you explore, is covered in terrifying “-1” symbols, meaning you lose points if you can’t fill them, meaning there’s a sense of constant momentum as you build and craft and build and craft and oh by Odin you’d better cover it all up before the game is over. HURRY.

I tackled Feast of Odin first thing in the morning, after a late night of Honshu and other games. I honestly thought this was going to kill me dead, that it would be the game whose churning depths carried me to the grave, but instead I ended up splashing merrily in its warm embrace as I realised all these many different elements are all easy to understand and represented by simple, visual tricks: flip a resource token to upgrade it; feed as many vikings as there are uncovered population slots in your great hall; slot iron cubes onto your ship to represent upgrades.

So there I was, goggles on and ready to dive right into this pool, completely unaware that I was going to smack my head on the bottom before my shoulders were wet. What a wonderfully concussive relief. That said, this is another game where you don’t have a great deal of interaction with anyone else. The biggest conflicts come from either trying to claim actions before anyone else, or racing to seize new resources before they’re depleted, but it’s not uncommon for players to want entirely different things and pass like longships in the night, not least because that action board is so big. Still, it makes the game surprisingly forgiving and a lot less cruel than, say, Agricola.

Feast of Odin is a huge, handsome, mighty-and-yet-gentle Nordic experience, like going to a Swedish masseur, so I’m pleased to present it with Paul’s Overall Best Game of BGGCon 2016 Award. I am hungry to play it again but, as a victim of its own success, I was told it’s currently sold out in North America. Fret not, a new print run is on its way.

I’m almost out of awards to confer but, before I finish, I will tease you with the tempting news that I’ve saved a couple of curious games for our next podcast, including the imperfect but hilarious scratch-and-sniff game The Perfumer, and I desperately want to revisit Feast of Odin for a full review, just as soon as it’s available. I’d also like to give a vigorous high five to the BoardGameGeek team for organising this and previous cons. This is my third BGGCon and, as ever, the atmosphere was one of camaraderie and inclusion, with what looked like an increasingly diverse attendance swelling the venue pretty much to capacity. My enormous thanks to my friends, new and old, for helping me learn and try a whole host of games right into the wee hours of the morning (oh God I have destroyed myself), and my incalculable gratitude to whoever it was in 15th Century Yemen who first had the idea of brewing the drink that is coffee.

Finally, extra thanks to designer and artist Daniel Solis, who wins the Best Person to be Stuck in DFW Airport With Award. Thanks to two flight hiccups that had me stuck for thirty hours (and potentially even more), I expected to be tromping around by myself for another eight hours. Daniel, whose work frequently emphasises diversity and all sorts of different mechanics, blessed me with Carcassonne and conversation and Asian food. Then I flew home and my suitcase broke.