Paul: One of the reasons we started Shut Up & Sit Down, arguably the biggest reason we did so,* was to get more people into board and tabletop gaming. We wanted to share something that we enjoyed. Board and tabletop gaming was (and largely still is) ignored by a lot of people who had preconceptions, even prejudices, about how boring, weird or bizarre it was. We don’t like that sort of thing and hopefully we’ve helped change that. Hopefully our invitation to the hobby has also been inclusive and reached out to all sorts of people.

You can imagine, then, how impressed we were to hear about the work being done by Different Play, a collective of experienced mentors reaching out to actively support diversity and inclusion in analog game design, both in terms of the kinds of games being made and also the kinds of people making them. The games industry, even the tabletop games industry, has a diversity problem and this can make it (among other things) intimidating and even outright unfriendly. Different Play wants to make sure that new and different designers are heard, published and paid. We asked them more about their work and their plans.

(Due to the complications of our job/our innate impressiveness,** it was Quinns who got in touch with the brains behind Different Play and talked to them about their aims and philosophy, but it’s me who’s collating and writing up their answers here. So, while it’s my byline, Smith did the legwork on this.)

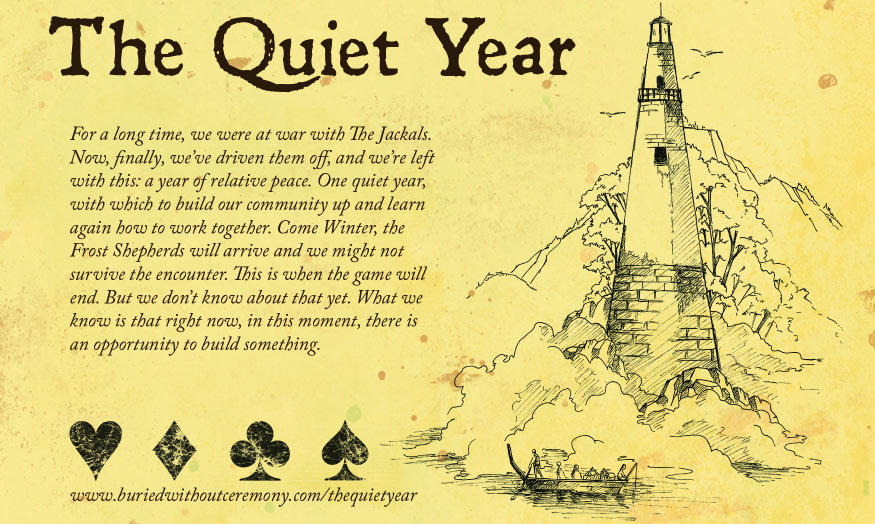

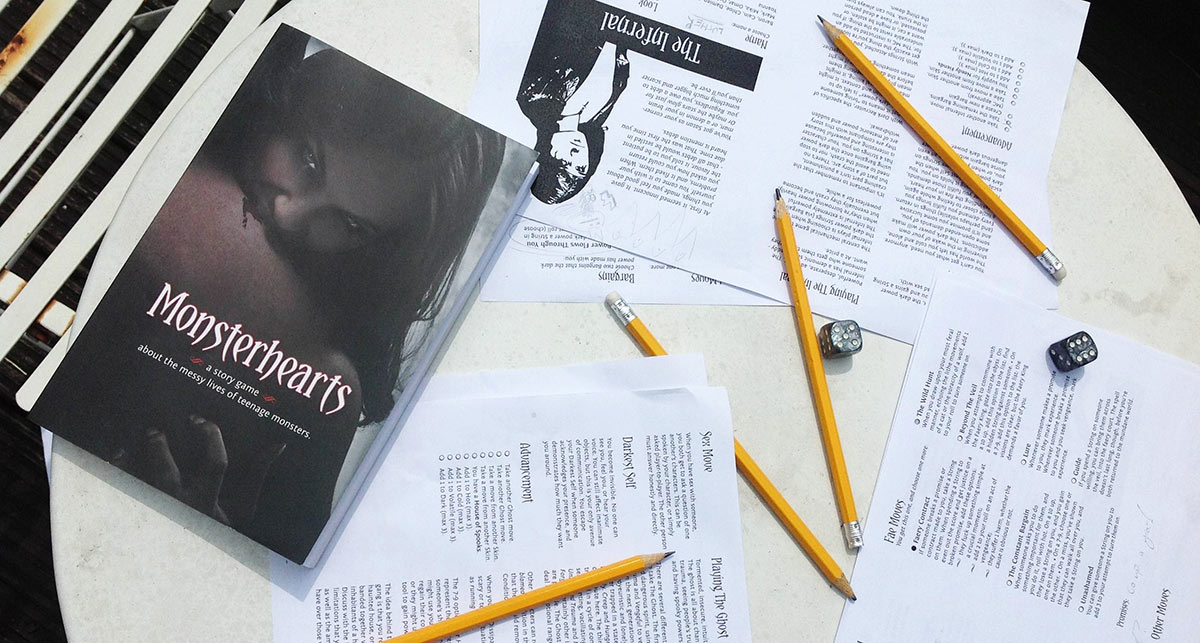

Different Play boast an impressive team of mentors and skimming their roster reveals names like Avery Mcdaldno, creator of Monsterhearts and The Quiet Year (below), games designer/journalist/author Lizzie Stark and Professor Jessica Hammer, of Carnegie Mellon University. They’re an interesting team and their combined talents and expertise mean they touch all kinds of areas of gaming. Using their experience and their connections, the team aims to pair “fresh, new designers with mentors, playtesters, artists, graphic designers and editors,” helping them through the design process every step of the way. Specifically, “We’re looking for designers from underrepresented backgrounds,” their mission statement declares, and they’re pushing original, unconventional ideas.

“It took me no more than ‘J-pop girl group fighting evil spirits’ to want to play Nicole Winchester’s game Hikaru no Aidoru / Idols of Light,” says James Stuart, a Different Play mentor who runs Story Games and who’s excited about the first games that Different Play will be helping out with. “Dylan Nix‘s Yesterday’s Tomorrow has a haunting hook: imagine being cryogenically frozen, and waking up several thousand years into the future, where everybody thinks you’re a monster. I think what’s most important is the heart, the reason why our authors want to write. For Nicole, it’s about struggling to maintain your friendships and who you are in the pressure of fame, and for Dylan, they want to explore what it’s like to be in a marginalized community, to be monsters.”

James isn’t just championing unusual plots, he’s also aware of the importance of new design ideas. “Whenever we have new players in one of the events I run, they are invariably awesome: they don’t know what ‘standard’ play is, so they bring heart and fire and surprise us all,” he says. “I think the same applies to design. For example, this article talks about the concept of default design: ‘Default design is a body of design choices, particularly thematic, that you don’t think about. You include them… because they’re prevalent in other kinds of thematically similar games.’ It doesn’t matter what part of the hobby you look at, in every corner, there’s a lot of default design going on.”

And he’s absolutely right. The familiar is safe and dependable. You know what works and how. New approaches can be strange, even risky propositions and you don’t know who they’ll connect with. Then again, there are plenty of people out there who haven’t connected with a lot of games so far, so perhaps entirely different approaches are just what’s needed.

“I think there’s lots to love about old school dungeon crawling, but it’s just one set of emotional experiences,” says Mark Truman, another Different Play mentor, designer of Our Last Best Hope (above) and the co-owner of Magpie Games. “There’s a thinness, often, to roleplaying where all the experiences become the same kind of emotional tone. A lot of the games we’re talking about (and that we hope this project produces) will hopefully continue to diversify that set of experiences and broaden the set of people invested in the hobby.”

The team have quite a lot to say about emotion and its role in storytelling and roleplaying games (the focus of their first projects) but, of course, new approaches to game design are only one part of what Different Play is about. When I joined the games design community, for all the individuality I may or may not have, I joined one that I had a lot in common with: one made up of white guys. Homogeneity makes everything easier if people see you as someone who fits in. Otherwise, it can make things much, much harder. Even without being actively exclusionary, communities can isolate those who are different simply by failing to fully understand them.

“I think that one of the big challenges that marginalized designers face, when working on first games, is the pervasive message that ‘this community wasn’t built for you,'” says Avery. “This message is structurally embedded in many conventions: operating without effective anti-harassment policies, childcare provisions, economic subsidies, or outreach to under-represented demographics. It’s present in cries about ‘fake geek girls’ as well as criticisms that atypical subject matter renders something ‘not a real RPG.’ It’s visible in marketing materials that so regularly default to objectified portrayals of women’s bodies that cater to patriarchal body standards. The message has a thousand iterations, and in sum they are pervasive. Feeling invisible or unwelcome can be crushing for new designers. Watching attention and support get handed primarily to white male designers can be crushing for everyone else.”

It may seem like a dispiriting appraisal, but Avery is in a good position to change things precisely because she knows exactly what the challenges are, adding that the other major barrier for marginalized designers is a practical one: resources. Cash.

“For new designers to be able to work on projects independently, they need disposable income and ample leisure time. Those are resources afforded by privilege. Those are resources that you are more likely to have access to if you’re cisgender, if you’re able-bodied, if you’re white. If we want diverse art, we need to support diverse artists. That means acknowledging the financial and social privilege that some artists have, and seeking to level that playing field. There’s this lovely mantra I’ve seen circulate Twitter, primarily coming from poor artists of colour. The mantra goes ‘f— you, pay me.‘ I’m excited about Different Play because I want to see bold new games that express diverse perspectives, and you don’t get that without putting money on the table.”

And that’s exactly what the Different Play Patreon is for. Patreon has grown into something of a crowdfunding darling over the last year and it’s perfect for individuals, groups or undertakings that need regular subscribers to support ongoing work, as opposed to the one-off projects of Kickstarter. Different Play are confident that they can pay a fair rate for the writing, art and editing that each of the games they are supporting will demand. Having just broken $700 per game, they’re also able to commission art and spend more time on the layout of the work they publish. This money, combined with their own collective mentorship, makes way for the sort of games they want to see, both in terms of production standards and design, and it’s in discussing their design processes that Mark returns to that subject of particular importance to the team: emotion.

“Roleplaying games hold my interest specifically because they are emotional products,” he explains. “It’s not enough to develop a game in which people roll dice and count numbers and score points. They have to care about the dice and the numbers and the points; they have to have an emotional engagement with the experience of playing the game.” It’s no surprise that they all have quite a bit to say about the Apocalypse World series, of which Monsterhearts is kin, and it has clearly influenced their development philosophy.

“One of the really vital things that Apocalypse World did, something which shook up the way indie designers were writing at the time, was to build mechanics around the principle of ‘fiction first,'” is how Avery puts it. “Its mechanics triggered on specific actions. They demanded and responded to what was going on in the fiction. I think it challenged a design approach that had become canonized and calcified at the time, of writing “conflict resolution” mechanics that treated all opposition as similar, that asked you to apply some traits to a die roll and then find out whether you earned your narrative stakes. Apocalypse World pointed out how toothless, distant, and inert that approach was. It was important because it challenged designers to think really concretely about how their mechanics engaged context, detail, and fictional positioning.”

While it’s still early days for Different Play, whose Patreon is only a few months old, they’re a confident and capable team who already have four quite distinctive projects under their wing from the designers pictured above, all of which are the sort of concepts you’re not likely to see anywhere else and all of which suggest a strong focus on narrative and, yes, emotion. James teases that the team already have a year’s worth of other potential projects to dip into and are “also making some connections in the board game world,” which could prove very interesting indeed.

What’s so encouraging isn’t that just they dare to be different, that they throw the doors open to new ideas, but that they so proactively court diversity and they’re ready for the challenges it presents. Different Play don’t just dare to be different, they know how to be different. In the year ahead, they’re going to be one to watch.

*Though you may have to check with Quinns for a size comparison.

**Delete as appropriate.†

†We don’t do enough footnotes around here.