[Following the tremendous success of Lord Smingleigh’s inaugral column on the nature of play, we invited gaming’s most storied gentleman to stick around! And then culled “The Ludological Investigation Society” as a title because it broke our headline box. Nobody tell him. I’m serious. He won’t shut up about it.]

It is a fact universally acknowledged that all board games are perfect. Who are we to stick our fallible thumbs in the board game pie? We have come for the experience the chef has planned through years of experience and talent, not the thrown-together improvisations of short-order cooks.

Except, no. This view is to disregard the most vital of components in board gaming: Humans. Sometimes it is necessary to change the game to suit the players. It is my honour to present to you an excerpt from an early draft of my life’s work and legacy: A Treatise on the Taxonomy of House Rules.

We begin with a section taken from Volume III, Chapter XXIV: House Rules for Harmony and Balance.

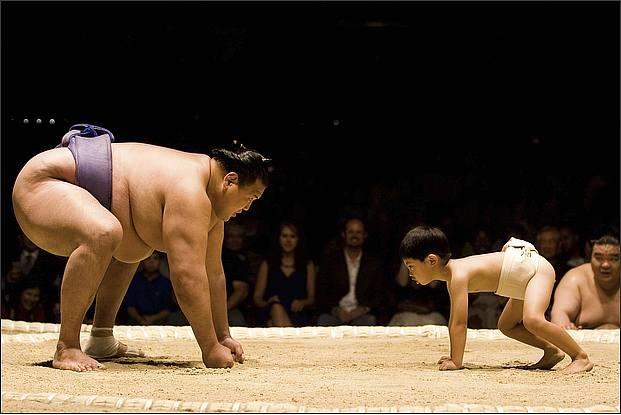

Finding new and innovative “legal” ways of grinding your opponents into the dirt so you can boast of your incredible victory is one of the joys of gaming, and this is an admirable mode of play in most settings. However, in real life there can be other considerations, such as “will this person play with me again?”, “how can this person learn if I’m crushing them mercilessly in two turns every game?”, and, of course, “if I play like a steroid-engorged lunatic will I be sleeping on the couch tonight?”. How is one to reconcile this with the terms of the Board Gamer Code of Conduct*? Many house rules handicap the overly-powerful or bolster the less fortunate. Other house rules restrict player interaction to reduce opportunities for overly competitive play.

It is an unfortunate fact that when teaching a newcomer to play a board game the teacher has an overwhelmingly advantageous position, leading to the learner often facing his or her first experience of the game as overwhelming defeat. This is particularly pronounced in long-form games like A Game of Thrones or Twilight Imperium, in which a couple of simple, totally understandable errors due to ignorance right out of the gate can utterly cripple long-term prospects in a multiple-hour playing session. The redoubtable Quinns, as a good Vlaadaist, has a sermon taken from the Orthodox Book of Vlaada.

“Teaching complex games can be a nightmare. One really beautiful solution that appears in Vlaada Chvatil’s games like Galaxy Trucker, Space Alert and Dungeon Lords are manuals that encourage you and your friends to learn just the basics, play a bit, then introduce new mechanics in each round. I can’t recommend this highly enough. These days, I’m fascinated in the art of getting a big, ugly game, then stripping its rules down as if you were modifying a commercial car for a race. Rip out the seats, the radio, the doors, and just get people playing. Then rebuild it as you go.”

This requires a solid understanding of the rules yourself, as you must know exactly how much to leave in, and what to leave out. It would be a poor game of Monopoly if you were to skip the “rent” rules or the “£200 for passing Go” rules for the first half of the game, but you could get away with leaving out, say, the rules regarding throwing doubles thrice sending you to jail, or you might choose to disregard the necessity to own all the properties of a colour before allowing building houses. It is also important to note that this is not only a useful teaching tool, it can be a fascinating exercise in ludological investigation. This sort of rules-winnowing can be a revelation with knowledgeable and willing participants. It can really help you to understand how the game’s systems interact to produce the game experience, and this notion will be returned to in a future column.

But teaching is not the only situation in which you might want to reduce the conflict in a game. In response to my cry for house rules at the end of my introductory column, Nick Shaw chipped in this gem of an example:

“When I play with Carcassonne with my wife, we house-rule that you can’t steal someone else’s city/road/farm. It takes some strategy out of the game, but still leaves enough depth and fun.”

House ruling out some of the game features that allow you to screw other players over is a fine way of allowing less-competitive players to join in a game. Lady Smingleigh enjoys Dominion, but she found that the “combat” cards and the “curse” cards to be more of a frustration than a pleasurable form of interaction. Since the game is easily adjusted by picking different cards for the buy piles, it didn’t need to be house-ruled, but the few times we’ve used decks that include the combat cards we’ve ignored the combat effects of the cards and merely used them for their deckbuilding face value. The heart of the game is the building of a well-tuned deck, and removing the ability to throw a spanner in each other’s works removed very little of what made the game enjoyable for her. Customizable card games lend themselves particularly well to this sort of “light touch” house ruling, as you can always build a Corp deck in Netrunner without cards that TAG the runner, or, say, a Runner deck that doesn’t use Viruses.

Of course, she professes complete pacifism, but after a few gentle introductory rounds of a game she goes for the throat and starts combing the rulebook and the Internet to find new and innovative ways to seize victory, preferably over my cooling corpse. She has recently expressed an interest in reintroducing the removed cards and rules, so I count this as a complete success, and am somewhat apprehensive about what manner of monster I have awoken.

Back in the dawn of time (early- to mid-90s), my hazy memory recalls that TSR released a CCG called “Blood Wars”. I think that was the one, a quick Google Image Search makes the card-backs look familiar. My single memory of this game, despite playing it a few times with deck-owning friends, was that in the beginning there was a “mustering phase”. This was a series of rounds during which no player could attack another, but could otherwise play cards and build up their forces as normal.

I’ve used this rule many times in other games. In fast-moving and competitive games it is often possible to sink someone very early on by crippling their economy or otherwise hampering them. By adding a mustering phase you can allow someone who might not be properly up to speed with the game to build and amass unhindered, and allow them to build a credible opposition despite not having the well-honed build orders and streamlined efficiency you doubtless possess. Then you unleash the dogs of war and allow the usual bloodbath to ensue, but at least you don’t end up beating up someone who unintentionally hobbled themselves at the start. I adapted this for Risk by giving each player a single territory (widely spaced apart), then filling all of the others with single-army “neutrals”, to give the players something other than each other to attack. By forbidding attacking other players until all the neutral nations they can reach are conquered, you don’t end up with two players out of several beating each other to impotence straight out of the gate, or one player wiping out another before the game is really underway.

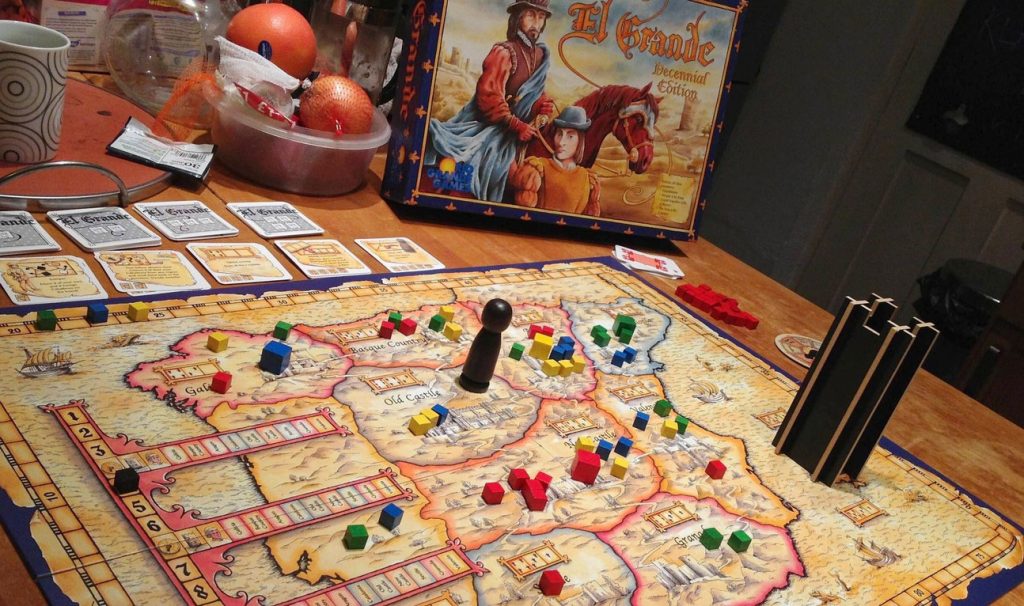

Speaking of Risk, in “campaign” games such as Descent and Risk Legacy, one player (or team, or side, or faction, or whatever) can amass such a massive set of advantages through good and/or lucky play that after a while other players start the game knowing they’re going to lose, which is pretty much the opposite of a good time. Again in response to my demand for house rules, this time by Laurie Cheers:

” In Risk Legacy you start each game with a number of missiles equal to the number of games you’ve won. One player in our group had won 6 times. We flipped the rule so that you start with a number of missiles equal to the number of times you’ve been the weakest player in the game.”

I like this; it bolsters the weakest player. It does, however, remove the reward for winning a game. I’d suggest this instead: Agree on a suitable way to determine standings before starting the game such as order of elimination, number of troops standing, territories held, whatever works for your group and the envelopes currently open. Upon victory, the winner flips a coin. On “heads” the player gets a missile, on “tails”, pass the coin to the second place player and repeat. If the coin gets to the last place player, the player gets the missile without having to toss for it. This gives a reward for winning (greatest chance of getting a missile), but tends to spread the missiles out somewhat rather than inevitably leaving them exclusively in the possession of one dominant player. This is a useful thing to bear in mind – if one player always wins, spread the advantage around a little. You might not balance it to the point where the dominant player loses, but you might be able to reduce the rate at which the game drifts ever further out of balance.

The next meeting of the Ludological Investigation Society shall pick up where we left off, where we shall cover house rules that increase complexity, challenge, and conflict. How do you like to bump up the challenge when a game starts to become predictable, ludonauts? How do you make a game that has turned altogether too chummy into a game that chums the waters?

Yrs. Sncr. &c,

His Nibs, A. C. “Custard” Smingleigh, O.B.E. (Withdrawn)

Brigadier, Her Majesty’s 3rd Mounted Extremely Irregulars (Catering), (Discharged, Dishon.)

*Section IX, Paragraph E, part a-ii: “A board gamer who intentionally loses the game shall be ceremonially beaten to death with Cluedo boards, and forfeit the use of the Ludological Society’s dining area”