Matt Lees: Paul, do you like temples?

Paul Dean: I don’t really know much about temples and I don’t come across them much in Lewisham. The last templeish thing I saw was the Grand Lodge of the Freemasons in San Francisco. It had some pretty unusual sculptures outside and I was too scared to go in, so I took some photos really quickly and then scurried off.

Matt: How many points do you think it was worth?

Paul: Pardon?

Matt: How many points? How many levels was it? Are they winning?

Paul: Oh I get it, this is a Babel review.

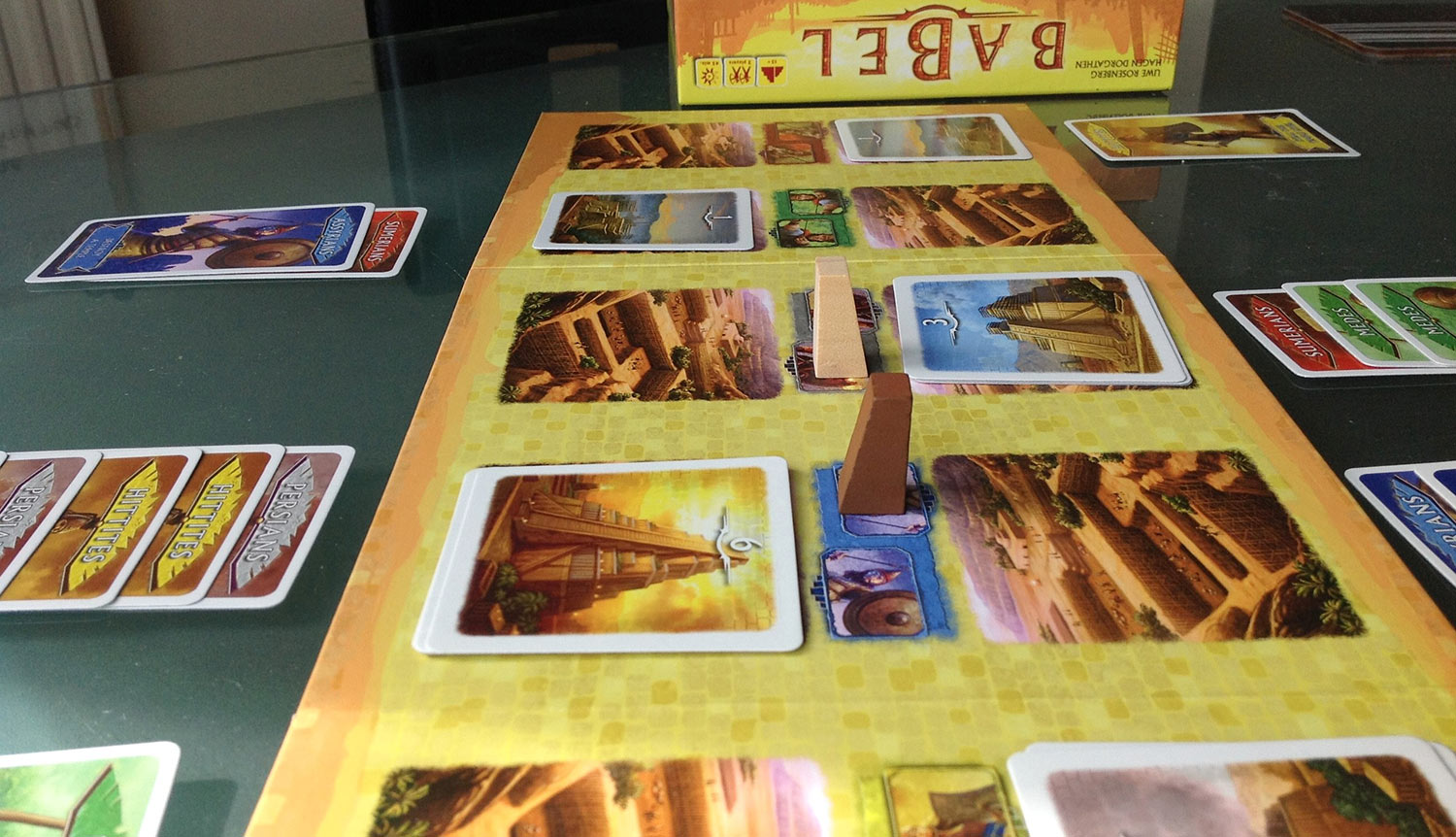

Matt: Babel is a game for just two players and the object is to build a better collection of temples than your opponent using the armies at your disposal. Each temple can be up to six levels in height and their height is their points value.

Paul: No, the object of Babel is to be a complete jerk by knocking over your opponent’s temples, like you’re kicking over sandcastles, and stealing away all the armies they’ve so carefully amassed. It’s a game about ruining things.

Matt: It certainly involves a lot of that too, but it’s a reasonably smart game about ruining things.

It plays like a nasty head-to-head version of solitaire, with carefully assembled stacks of army cards letting you build increasingly taller temples, or unleash powers that set the player opposite back. It’s tempting to whack a ton of cards in one place to create an unstoppable army of doom, but much like solitaire you’ve got to be careful about prematurely stacking things up.

Deploying armies from your hand is easy: there’s no limit to how many you can place in one turn. But moving these armies sideways between the different temple locations is slow and relatively restrictive process. It’s thrilling to deploy four armies at once and to immediately cause all sorts of grief, but doing so will often leave you hamstrung afterwards for several turns.

It’s classic card game stuff, really – the thrill of solving the endless conundrum about how best to chain a combination of moves. The more cards you play, the more temples both players build, the more possibilities there are for conflict, for temple destruction, even for nicking the tops of your opponent’s temples and sticking them on your own. We aren’t clear on the logistics of that, but it’s a wonderfully horrid thing to be able to do.

Paul: Yeah, “mulling” is the word I’d associate most with Babel, because I found myself mulling an awful lot. Really frowning as I tried to work out what I wanted to do next, or what I wanted to do after what I did next. I’m not always good at that sort of planning ahead but, y’know what? I think Babel had about the right amount for me.

Maybe that’s because its mechanics are all pretty straightforward and there’s never too much to think about. Each player has five building sites in front of them, all fresh and new and just waiting to become the home of a shiny new temple that’ll surge skyward. They also hold a hand of cards that are made up of armies (called “Nation cards” in the game, but as far as I’m concerned they’re all armies, so there). To build a temple level on a site, you need to deploy that number of armies in front of the site and have one of the relevant temple cards available. These are drawn off a deck by both players, making two ever-growing piles, and you can always snatch the top card off either pile. There are more cards for the lower levels, fewer for the higher ones, so starting a temple is always easier than finishing one.

Matt: Your first couple of turns are pretty humdrum. You both start with level one temple cards, so you can get going right away, but waiting for more cards that you can use might have you hanging on for a while. Waiting for army cards that you can use might mean the same, too, so you bide your time.

Yeah, so about those army cards. Each of your building sites corresponds to one of the five colours of army. To perform any construction on a temple site, or to deploy armies below it, you need your little worker pawn to be sat there. To move that worker, you need to burn a card of the same site colour. So your turn might have you burn a grey Persian card to shuffle that little guy sideways to a one storey temple on that site, then have you deploy a second army of any sort at that site to allow you to add another level, then grab a face-up card for a level two temple. Hooray! Congratulations! That’s what I call PERSIAN PROGRESS.

Paul: Sure, but that’s not really what all those armies are doing, is it? Is it? Sat there by themselves, those armies just allow you to build bigger things, but as soon as you have three armies grouped together in a row, they start to cause trouble. The Sumerians become sneaky. The Assyrians become… asses.

Lay down three Medes cards and you can force all the armies of one colour to flee from the site facing them. The fearful fools run away! Group three Sumerians and you can steal some of the army cards from the site opposite. Put down three Assyrians and you knock down the temple across from them. Three Hittites are even worse, because those cheeky fellows baldly steal the top of the opposite temple and add it to your own. It’s heinous. It doesn’t matter if there aren’t all the intermediate levels, either. They’re both thieves and appalling architects. Something should be done about those guys.

Matt: Last, you’ve got the Persians. Those fellows allow you to skip a temple level, so you can stick a third level temple card onto a first level one, as long as you have enough armies deployed at the site. DOPPEL PERSIAN PROGRESS.

But hopping around between sites quickly burns cards, throwing a spanner in the works of that lovely Persian Progress. There’s a balancing act between moving around to give different building sites attention and hoarding cards so you can use the army powers. Pop to Persia too many times, and you can say goodbye to that delicious Progress.

All these different army powers mean that, as well as building your temples the usual way by plopping armies next to them and slowly adding layer after layer, you can find ways to cut corners, slow down your opponent and generally be a bit sneaky. What makes Babel a bit special, though, is how much you’re allowed to do on your turn. That’s the rub.

Paul: It very much is. On your turn, you’ll draw three more army cards and then you can move your pawn to as many sites as you like, just as long as you have the cards in hand to burn for each move. You can deploy as many armies as you like, providing you have them to hand. You can trigger their special powers as many times as you like, providing you’ve got three armies grouped together.

Ah, yeah, that’s the thing. Once you start deploying more armies on top of other armies, getting their powers to trigger becomes a bit difficult. When you use a trio of troops, you have to throw one of them away. You might not have the luxury of deploying a third army of the same colour on top of them later, because you’re often short for cards. You’re only ever drawing three, you’re burning them to move your pawn around and it’s just as important to have anyone at a site, so that you can build, as it is to group armies.

Sooner or later, your armies are a mismatched mess, a rainbow of forces. On your turn, you only get to perform one single movement of these armies, one re-jigging of three cards from one site to another. Always three cards. It’s like cutting a deck. It’s a really slow way to rearrange your armies and you can feel them crawling their way from site to site, sweating in the midday sun.

Matt: What this means is, after those slow and early turns, you build up hands of armies and start to plonk down bits of temple. Then suddenly you start doing crazy chain maneuvers where you’re throwing down armies all over the place, using some of them to steal your enemy’s stonework, using others to trash the things they’ve worked so hard on, and causing their forces to defect to your side. Oh no! Paul has Assyrians coming out of his… Assyria! Three of my Medes will send those guys running.

You look at the temple levels available to you that turn, steal a level of a temple, then add to that temple level and then skip the next temple level, sticking something even grander on, all by some judicious army deployment. If you’re smart, you do a little rearrangement of your forces. Maybe you’ve just deployed half a dozen cards, so maybe you’ll lie low for the next couple of turns, building up to another very cunning play. Or maybe you still have a few troops in hand for something you have planned next…

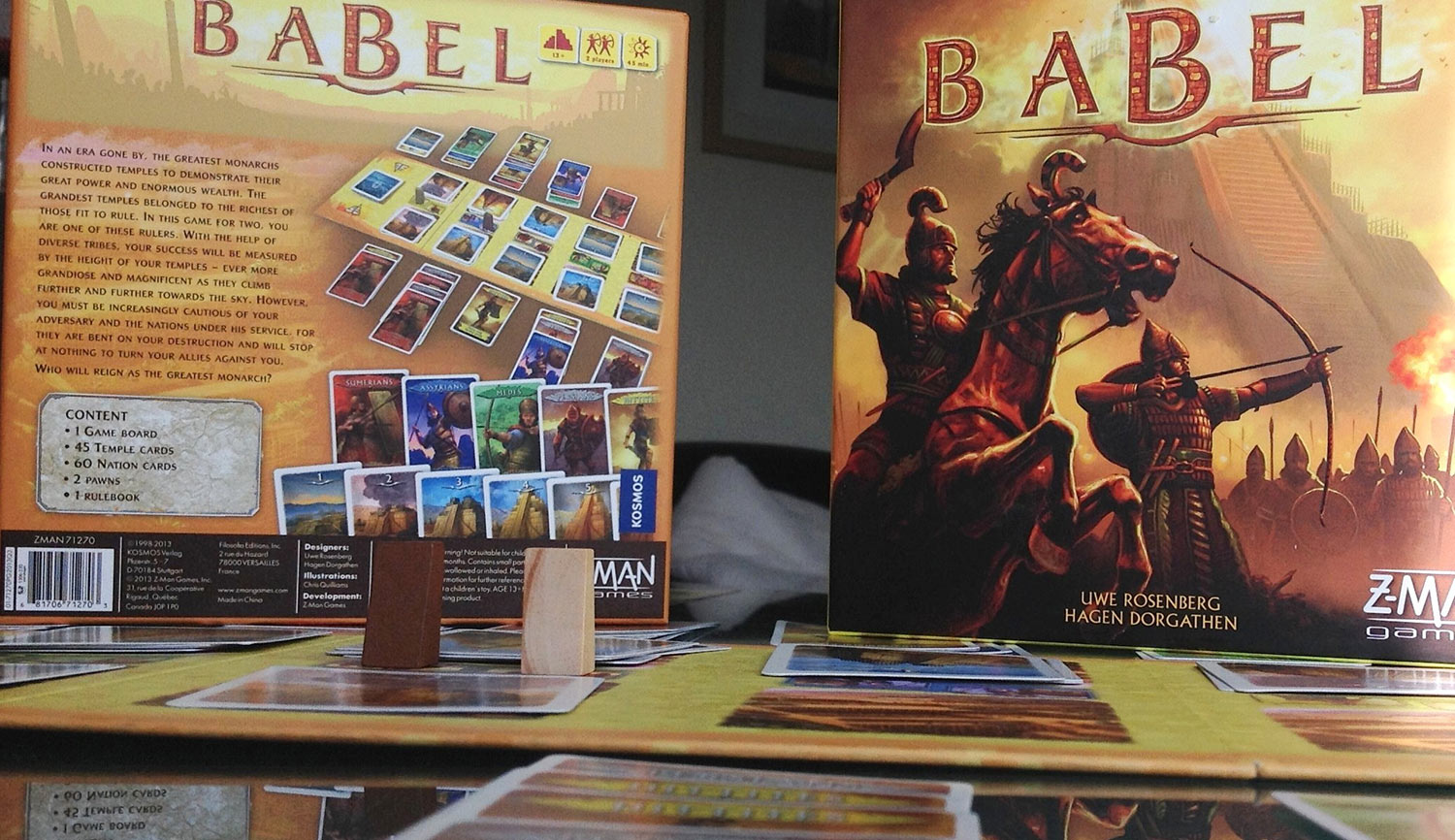

Paul: After a slow beginning, I started to find Babel very cool indeed. There’s not too much to have to think about, because you’re only ever looking at two face-up temple cards and five different rows of temples and armies (and yeah, it’s a bit of a brown game without any particularly sexy components), but all this is quite enough to keep your brain ticking over. You’ve always got a pretty good picture of who’s doing well and what threats are out there, but there’s just enough hidden information that you never quite know what’s coming next.

You’re never entirely safe, either. That sparkling, six-level temple that took you so long to build now looks just like the one at the end of Ghostbusters. Then, like Bill Murray, Matt comes along with three Assyrians and trashes the whole thing. A game of Babel ends when there’s a big enough points difference between the players or when the deck of temple cards runs out, but until that happens you can never be sure how safe the leader is. An unchecked team of highly-trained Hittites can still steal the sixth level of a temple that’s been built on so much sweat and stick it in the mud opposite, effectively conjuring six points out of thin air.

Matt: Babel’s a pretty smart game. It’s not all that big and it’s not really very glamorous, but it really lets you test your wits. It’s a relatively quick game, maybe taking you thirty or forty minutes, and it has a lovely sense of pace to it. You build up stacks of armies, you build up hands of cards, then you blow them all and start the process over again, silently drawing more cards, quietly forming your next plan.

Paul: I thought Babel was going to be boring, but it turned into one of the best two-player games I’ve played in a while. Without getting too complicated, it still succeeds in rewarding you for planning, for taking advantage of opportunities and, when the moment arrives, for being very mean to your opponent. Shut Up & Sit Down recommends it, much as we always recommend being mean to your opponents. THAT’S WHAT THEY’RE THERE FOR.