Paul: Hey Matt! Quinns and the others are going down the pub and they asked me … well, they didn’t ask, exactly, but I thought you might get … erm, wanna come?

Thrower: No. Can’t you see I’m working?

Paul: Is that a ledger? Are you an ACCOUNTANT? I presumed you lived on secret backhanders from the Pentagon. What’s this game here?

Thrower: That’s A Distant Plain. It’s got solo rules, so I was hoping to play during my break. But I think I made a poor choice.

Paul: How so? It isn’t very good?

Thrower: I wouldn’t say that. But let’s step back. A Distant Plain is a game about the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan and its ongoing consequences. In this, it’s an astonishing rarity. Politics isn’t generally done in board games which, when you consider it, is an appalling dereliction of duty. These are social games, things you drink beer and chat over instead of hunched on the sofa, half-dressed, shivering and alone before a flickering flatscreen.

Paul: I agree! Have y-

Thrower: Political commentary is something these games should be superb at bringing forth, offering players new insights to treasure and discuss. Look at War on Terror, or even Train. Yet only a tiny minority of titles take this opportunity, almost all of them wargames. Volko Runkhe, one of the designers of A Distant Plain, seized the chance with his previous title Labyrinth. But this is arguably a rawer experience because the war in Afghanistan is an ongoing political hot potato.

Paul: It sounds delicious.

Thrower: It is delicious.

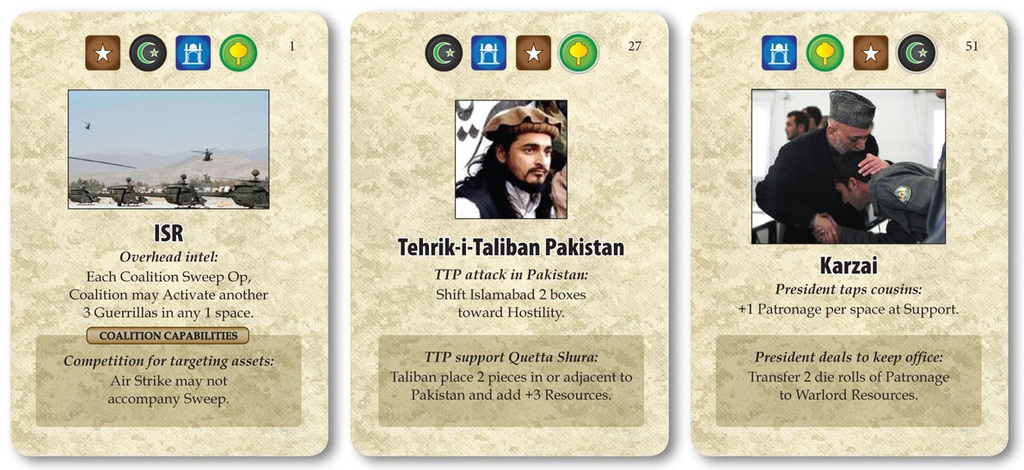

Now, there are cards in the game, though it isn’t a card driven game in the sense we’ve previously discussed. Each turn, a card is flipped off the top of the deck and up to two of the four factions can use it to act. They can either take the event on the card, or choose from a peculiar menu of other possible operations depending on their faction and whether they’re acting first or second. If you act one turn, you have to pass the next, forcing players to plan ahead.

Paul: Wait, four factions? I thought wargames were all two player?

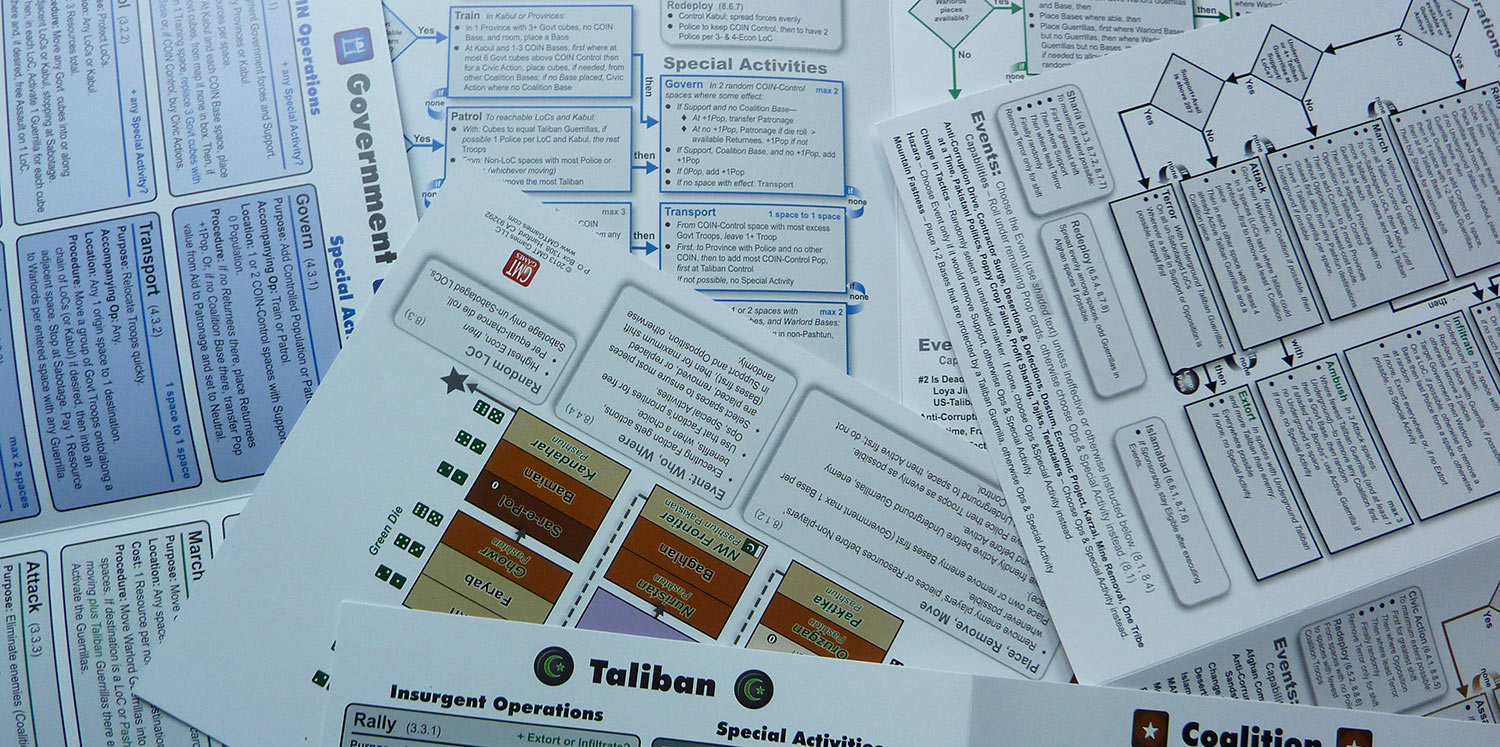

Thrower: Most are, but this is a notable exception. You can play with two players or three, either by allowing one player to take two factions or having the play of the others decided by one of the dizzying flowcharts provided. But it works best with one player for each faction: the western Coalition, the Afghan Government, the Taliban and the old Afghan Warlords. Because the truly amazing thing about this game is how it recreates the tensions and interdependencies between these factions in modern Afghanistan.

I promise that unless you’re an expert on middle-eastern politics, A Distant Plain will transform your view of the Afghan conflict. What appears black and white in the news will be repainted by this game into a sludgy kaleidoscope of morals. The best showcase for this effect is the co-dependency between the Afghan government and the coalition. Like all the factions, they have their own win conditions. The government wants to control board spaces while increasing what the game calls Patronage, a complex idea which can partly be boiled down to political corruption.

The coalition meanwhile needs to win the support of Afghans while keeping as many troops at home as possible. To gain support, it usually has to allow the Afghan government to control spaces and – get this – it can spend the governments’ own resources whenever it wants. Neither player can work toward their own win condition without offering a helping hand to the other. Their relationship needs to stay sweet, but is constantly buffeted by bitter currents of jealousy and recrimination, an extraordinary and unique dynamic.

Paul: What about the other factions?

Thrower: Oh, they get their share of the action. The Taliban seek to control spaces for themselves, and build up their infrastructure, both in Afghanistan and Pakistan, while the Warlords look to stockpile resources while ensuring that no-one has overall control, allowing them to maintain their independence. Occasionally they’ll be unlikely bedfellows with the counterinsurgents: even the Taliban and the Coalition might snuggle briefly together if they’re both under the cosh.

Paul: That’s really not an image I wanted. All those beards…

Thrower: Forces are represented by cubes and cylinders, but their capabilities vary wildly by faction. All the players can raise new troops, move and fight with them, although the precise mechanics differ. Terrorist cells, for example, need to be either activated or discovered before they can be eliminated by conventional forces. But there are more subtle effects available. The Taliban capability to recruit by infiltrating government or warlord units and making them switch sides is particularly vicious.

Paul: It sounds complicated.

Thrower: Well, it is and it isn’t. There are only eight pages of rules. It’s just that, like Labyrinth, there’s bewildering circularity about the game, an interlocking of systems and effects that makes you feel like you’re working the mechanisms of a gigantic clock. It makes it hard to get to grips with because wherever you start there’s always something else you need to know first. And understanding the strategy can initially seem overwhelming, although this also gives the game impressive longevity.

Paul: It sounds extraordinary. How come you think it was a bad idea to bring it to work?

Thrower: Well, it is extraordinary. It’s history in the making. But with all those interdependent effects, all those different resources to track it just sometimes feels uncomfortably like doing accountancy rather than playing a game. Each time a player takes a turn, something changes on the board, and that has a whole bunch of knock on effects. Control has to be re-calculated, resources deducted, some counters go up, others go down. It’s really irritating having to keep track of everything but it’s essential that you do it properly, because the victory conditions of each faction are based on these factors.

Ultimately, it’s entirely worth the effort of learning and playing because while an undoubted simplification, it offers tantalising glimpses into the alien culture and politics of another land. A Distant Plain doesn’t moralise, it just helps you understand why the conflict is such a drawn-out morass and leaves you to make your own conclusions like an adult. It even contains pointers as to why Afghanistan has proved such an irresistibly hellish honey trap to strategists down the ages.

Paul: Matt, you’re dribbling again. So, um, whose accounts are you actually doing there? Who’d entrust their accounts to someone who’d spend their lunch hour re-creating the invasion of Afghanistan! Ha.

Thrower: These are accounts of the fallen, Paul.

Paul: Oh no

Thrower: All the people, soldiers and civilians, guilty and innocent, who’ve died on battlefields through the ages; someone ought to record their names, their deeds, so their sacrifices might be remembered. And that task falls to me.

In the basement, I actually-

Paul: You know, I’m just going to stop you there, no thanks, because this has happened before, so, I have to actually have to immediately leave to make a phone call, in Liverpool, for no reason. So… um, bye!