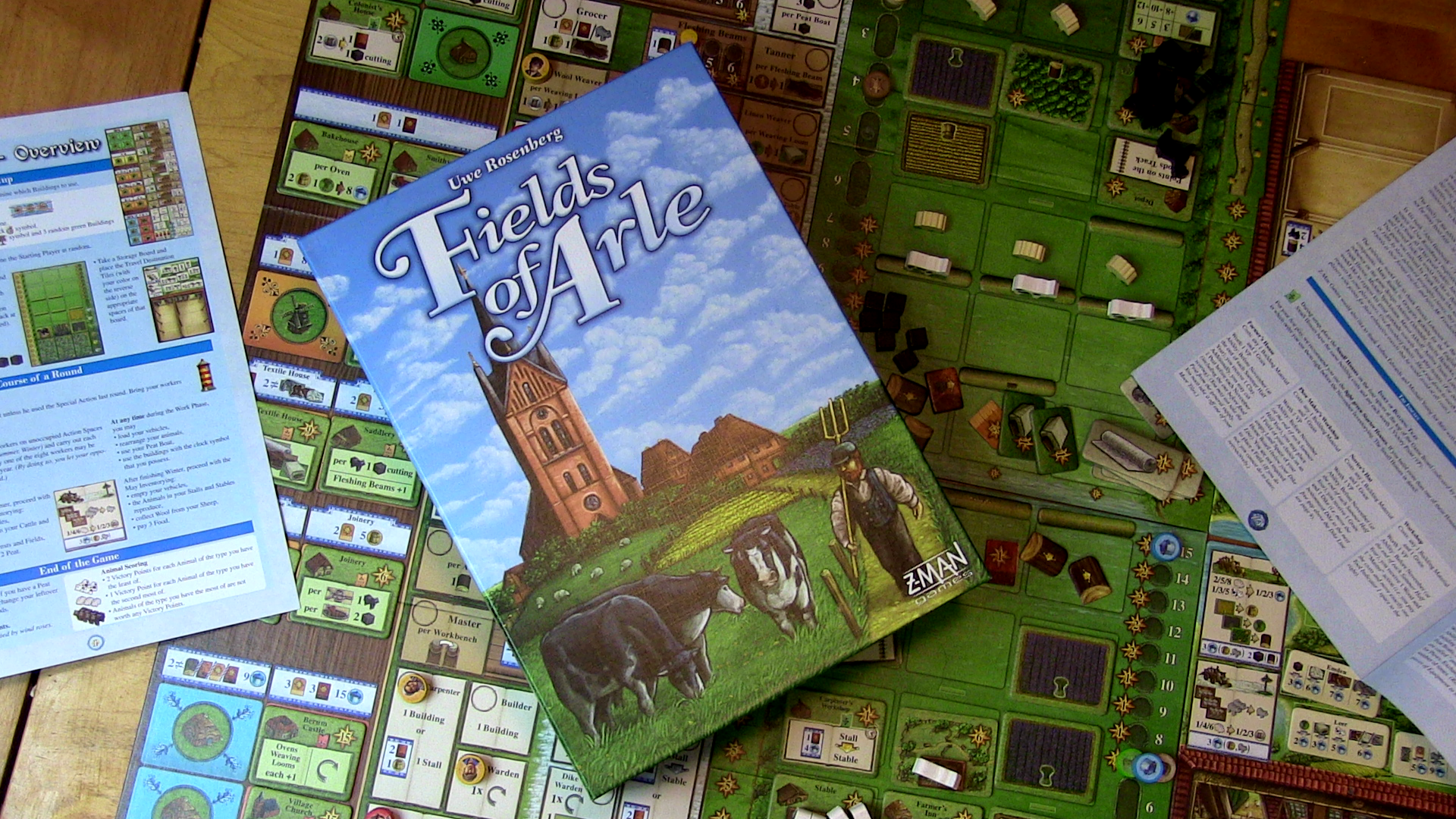

Paul: I’m not sure what it is about all this grit and graft that hooks me. Uwe Rosenberg keeps making games about hard work and manual labour and there I am again, scraping at the soil or sweating at the forge as I worry if we have enough food for the winter. My servile son shoves another horse into the stables, while my wife trudges through the fetid, bubbling peat bog that marks the edge of our land. There is so much that needs doing. Fields of Arle is the greatest farming challenge I’ve ever taken on and… is it weird that I relish that?

Fields of Arle is the liquorice allsorts of agrarian living, offering you as many bites of just about any flavour you fancy. Do you want the soft-centred delight of sowing huge tracts of land, or the vaguely coconut tang of building specialist structures, or the chewy pleasure of cramming cows in everywhere you can? Cows in all the fields? Cows up on the levees? Cows indoors and out, their bulbous udders and arses poking out the windows of the sheds you’ve squeezed them into? With SIXTY WOODEN ANIMALS in the box, this is a game you can gorge yourself on and, while that sugar rush might be a little unsatisfying in the end, a little excess is good for everyone sometimes.

Like its big box Rosenberg cousins (A Feast for Odin, Caverna, Agricola), Fields of Arle is a whole bunch of tough toil built upon worker placement foundations, that mechanic where you have a certain number of dependable minions who you shove out into the world with instructions to each accomplish specifics tasks. Usually, claiming a task with a worker locks out that same possibility for your opponents, though things work a little differently this time around.

But before I get into that difference, let me come at you with another: unlike most of its peers, Fields of Arle never lets you recruit any more workers. You start with four and you end with four, meaning you’ll always be choosing just a handful of things to do every season. It’s a restriction that makes things leaner and faster, though I also found it as welcome a surprise as leaping a stile to land in a cowpat. I want so much. I can have so little.

Let me come at you next with a surprise: this game is head-to-head. When I dived into this box I did not expect to pull out only two tracts of land, just two estates that develop in direct competition with one another. An estate-off. There’s something much more brutal, even intimate, about only having one opponent who you wrestle over all this campestral candy with, both of you scrabbling for cows and ploughs again and again.

Each player begins with a huge stretch of mostly empty land, two ploughed fields, a single horse in a stall and massive, mournful, misty moors that lie untouched and uncaring (and giving you a starting points deficit). Those moors need clearing and those fields need levees to hold back floodwater. There’s a big, wide world of animals and plants and even wagons out there, just waiting to join you, but you don’t have any damn room.

So you face a three-pronged challenge. As well as building on your limited, fertile land, you’re always looking to clear more space for your next stable or crop, but you’re also engaged in a constant dance with the player opposite. You both try to anticipate what you might need next from list of agricultural actions and assets as long as a summer’s day. There’s so much to be done and, I’m sorry, but you’ll never do it all.

Right from the start, this gives Fields of Arle a strange sense of ragged momentum, a feeling that things are always getting away from you. Whether you’re building a shed, hauling in more animals or deploying your first plough, each action you pick is quick and specific. Some are free, but many cost you resources like clay, wood or the peat you gain as you clear those moors. Most importantly, you could do almost all of these things better if you just spent a little more of that precious time improving your tools.

Many actions have an associated tool, a counter next to them that you can increase so that, next time you cut trees, you get more wood, or next time you tan hides, you make more leather. The catch is, improving these tools is itself an action, the Master action and… wait for it… the Master action itself starts off not being all that great. You really need to take that action to improve that action so, later, you can improve even more tools and turn yourself into a logging, weaving, digging, slaughtering FARMING MACHINE.

Except spending time improving your tools is not spending time vacuuming peat or compressing cows. Given that this is an Uwe Rosenberg game, you can’t rely on other people to feed you and some of your efforts must be put towards ensuring there’s always something, animal or vegetable, that you can eat tonight. This gets easier as your farm expands and becomes more self-sustaining, but it’s another early game headache as you and your opponent squeeze past each other to try to drag another sheep home.

And that opponent is a jerk. If they’re logging, it means you aren’t. If they’ve gone to market, it means you can’t. If they’re cutting peat… FOR PEAT’S SAKE did they know you needed that? But, dear, readers, there’s other things I’ve been hiding from you. Two tiny details I chose to omit. You see, you can actually repeat an action your opponent has already taken, as long as you’re willing to pony up some of your food. By choosing the special Labourer space, you can imitate another action, but this is a one shot opportunity and that food is both a vital resource and contributes to your final score.

Even better, you can also defy time itself. All of Fields of Arle’s actions are divided into two columns: summer and winter activities. You’re not wholly confined to just performing those of the current season but deciding to, say, tan leather in summer (so improper) comes with another penalty. This can only be done once a season and whoever snatches the opportunity sacrifices going first next season. It’s a leap that may well be worth it, but going first is nearly always an almost incalculable advantage.

Like so much in this game, it’s all about context, and the constant back and forth between you and your opponent is a bucolic badminton of response, evaluation and adaptation as, THWAP, you react to the new position they’ve just put you in. At the same time, Fields of Arle can be remarkably generous.

There aren’t a great deal of dependencies or specialisations to worry about and while building many late-game structures does require you to have amassed a lot of materials, even surplus resources can score helpful points and misplaced ambitions will rarely dig you into too deep a hole. While the game is broad in what it offers, it’s almost as shallow and safe as a puddle. You splash away merrily, knowing that while it isn’t easy to play skillfully, it’s also hard to fail outright.

Speaking of context, my favourite part isn’t found in earning your dinner or expanding your holdings, but in taking trips to sell your goods for food and, like everything else, earn even more points. If (and that can be a big if) you end up deciding to make a whole lot of leather and linen, and if you’ve also constructed a wagon or two (slap some wood on a horse, that’ll do), you might decide to sell your things in a town. Let’s hit the road.

Travel! Culture! Other people! Each town has different demands and, while you don’t have to fulfill them all, you’re constantly evaluating if you think it’s worth making a trip with what you have right now, waiting another season or instead using your wagons to convert more raw materials, as you frequently need to upgrade your wood and clay to timber and bricks.

All this is up to you and almost everything has its value both during play and at end game scoring. Did you make a whole bunch of wagons that you never even needed? They’re worth points anyway. Forget to use all that grain? It still has some point value. Clear empty land you never built on? Nixed a point deficit! Make surplus bricks? Brick points. Too many shirts? Shirt points. Overdo it with irrelevant buildings? Points. Cow fest? Points. Shear too ma- POINTS.

It’s not about whether you’ll be a success, only how much of a success you are after all those attempts to sidestep your opponent, after realising that upgrading your tools signalled your intention like a cockerel bawling about the coming dawn, after managing to beat out enough leather to fulfill your large and luxurious deliveries. At the end, in spite of all the challenges, you’re still so sated. Bloated, even. High on points.

It might be overwhelming if it weren’t so forgiving, but in so being broad, shallow and generous, Fields of Arle loses its edge a little and all that ragged momentum can lead to a gently cushioned finish. Furthermore, because trying a bit of everything inevitably works to at least some degree, subsequent games can feel like they play rather samey, even though you might develop quite different estates. Whenever your plans don’t quite work, you just grab for something else because you can likely use it for something, that it can help somehow. It’s like taking fistfulls of sweets and cramming them into your mouth, knowing it’s not as good as proper dinner but will do for now.

And that’s why I don’t quite feel the love this time. This is probably the Rosenberg big box game that has excited me the least, though that’s like saying it’s the pina colada that has excited me the least. This is still an enjoyable, colourful and complex creation, but I’d rank it below our fondly-remembered favourites A Feast for Odin and Caverna. If you really must have more Rosenberg, have the cash to buy something big and would also like the particular sort of focus that a tight, two-player experience can grant, this is still a fine game, but it should not be your first port of call.

True story: The first job I ever remember wanting, when I was five, was that of a farmer. I was attracted by the variety of all the different tasks, the idea I could be looking after half a dozen different types of animal, the rolling fields full of so many kinds of crop.

I had no idea what modern farming was really like, that today’s agriculturalists must harvest corn with their teeth and machinegun escaping livestock before it makes it over the wire and back to the allies. I didn’t know that you had to manually extract the milk from apples, or expertly negotiate the bacon out of sheep, nor that many farms specialise in just one single yield. I’d likely have ended up harvesting huge fields of marbles, uranium or endlessly howling raisins. At least with Fields of Arle, my five-year-old farming fantasies can finally come true.