Thrower: Vietnam. Sex, drugs and terror lurking in the tropical night. If even half of what you read about it is true, then this was the war to end all wars: the war of America against itself. The Viet Cong were just along for the ride.

This was my generation’s World War 2, the conflict from which 80’s society forged martial myths of heroism. Yet, hard as it tried, pop culture couldn’t quite scrub the filth away. Always there were undertones of dirty warfare, of eventual failure. It wasn’t ideal hero material, but it was all we had. For me, that complexity made it all the more compelling.

Then I read Dispatches. This account of a journalist’s experience in the conflict is the finest book on war I have ever read. As well as the history, there is an important lesson. Dispatches taught me that war can be both beautiful and terrible at the same time. That it was okay to hate war and love militaria. To be a pacifist and to play wargames. Reading it made a piece of distant history into a personal thing, a hot piece of literary shrapnel lodged close to my heart.

So I’ve waited years for a definitive Vietnam game to explore this dichotomy. The best I’ve played is recently re-released card-driven title Hearts and Minds. For all its qualities, it couldn’t quite capture the politics of the war. It’s a little too clean and predictable. In the films and books, the high command always reeked of chaos, whatever the propaganda said. A real Vietnam game should capture that, should make the players confused, uncertain, afraid.

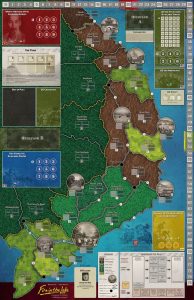

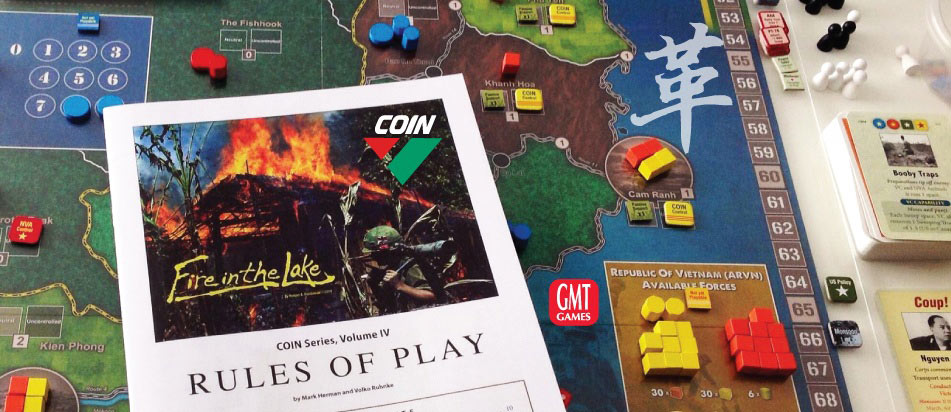

When I first played Fire in the Lake , it seemed the opposite. It’s a COIN game (just like A Distant Plain, if you remember our review of that war game of modern Afghanistan), and these are more systematic than most wargames. That’s one reason they’re popular with heavyweight gamers outside the niche. Yet for all that depth, their predictability sits uncomfortably with the popular conception of Vietnam. There’s little in the way of hidden information or dice. Combat is a fixed exchange of units based on terrain and troop quality. When I read the rules, the Vietnam I knew, the Vietnam of tunnels, booby traps and airborne assaults, wasn’t hiding in ambush between the lines.

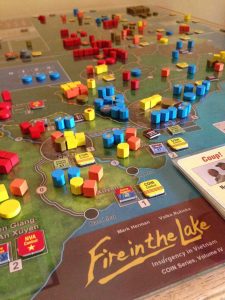

It tried to compensate. You can see where guerrillas are on the board but while they’re face down “deactivated”, they’re untouchable. They have to be activated, either by being sent into action or uncovered in a sweep operation, before they can be attacked. So watching them mass in provinces, knowing there’s nothing you can do about it, is one of the bitterest, most frustrating experiences in gaming. Naturally, that means the Communists do it at every opportunity.

Then there’s the way the whole board can change state in a moment. When someone picks a full operation, it potentially affects every map space, providing the player can pay for it from their resources. It doesn’t seem very realistic. But it makes for a terrifying wellspring of strategic depth to draw on. These wheels within wheels have tiny wheels inside them.

So while I gorged myself on the strategic meat in the game, I stayed hungry for the soul of Vietnam. There’s a deck of event cards featuring important moments from the conflict. Many are powerful, like “Uncle Ho” which gives the ARVN player two operations and a resource boost to pay for them. But while one is in play, the one that’ll arrive next turn is visible to all the players, devoid of surprise. The way the position of all the guerrillas on the map was clearly visible really bugged me. It was too clean, too clinical for the conflict that taught us to love the smell of napalm in the mornings.

The deck for Fire in the Lake is enormous. You only use a fraction of it each game, mixing in “coup” cards that act as a timer, allow players to redeploy troops, and change the South Vietnamese government. So far I’d stuck with the short scenario: at three hours, that seemed enough. But what if the things I’d been missing were in the cards for the longer game? I owed it at least one more shot.

Longer scenarios use pivotal events, a unique card for each player representing a key moment like the US Linebacker II campaign or the ARVN Easter Offensive. These can trump standard cards, and pivotal events can themselves be trumped by bigger pivotal events. The Tet Offensive beats everything, just like real life. They bring some welcome human drama to the game. Critical plays become a Mexican standoff, each faction willing the others to crack and play a pivotal event first.

Four players also bring an element of politics. The capitalist and communist forces are allied, but only one faction can win. So players are torn between helping their ally and helping themselves. The Americans need political goodwill, and troops at home, but to get it they’ve got to advance the South Vietnamese cause by helping them take territory. The Viet Cong and North Vietnamese are balanced together on a similar razor.

Player count in Fire in the Lake reflects unsettled history: did the Communist command have direct control over the Viet Cong? Play with two or three, and you’re saying that it did. With four, you’re saying the VC was an allied, but distinct movement. Wargames are a wonderful way of exploring what-if questions, but this was something more. This was history built right into the metagame.

It’s an impressive standard of research. And as the long game unwound, I could see it everywhere. Most of all it was in the cards. There were events I’d never heard of. The longer game deck hid all the politics, the US home front, the casual racism. With so much academia on display, it made me wonder. Perhaps all those books and films were wrong. Perhaps I was wrong. Perhaps Vietnam wasn’t like that at all.

It came back to those highly visible guerillas. I did a little research. And unsurprisingly, Fire in the Lake had it right. Hollywood taught us that Marines lived in terror of the VC descending on them like jungle mist, and dissipating just as quickly. In fact, they knew where the enemy was operating. It was finding and killing the Commie bastard that was so difficult. So: see the cylinders, but can’t destroy them.

Suddenly, everything else started to fit. I’d never thought of the Viet Cong as terrorists. But there they were, performing terror operations and playing events representing bombings and assassinations. I’d never thought of Vietnam as being an insurgency. But there was the South, a weak, corrupt state surviving only because of American patronage. We’re taught that Vietnam was a regular war, just one in which the faceless, cheating, Communists refused to fight fair. But it never was: it was the first conflict in which a mighty war machine got restrained by politics, tried to fight a new enemy by the old rules, and lost. It was the first war of the modern age.

This is where Fire in the Lake earned its space on my shelf. It sometimes feels too cumbersome, too predictable for the subject. But it cuts through the clouds of dope smoke to show us the war as it happened, not as shown through the warped lens of popular culture. This was no heyday of glamourised violence and countercultural mystique, but a ragged mess of politics, terrorism, and death in the service of broken ideologies. A tragedy of barbarism in the name of very little, like far too many wars down the ages. That we finally have a wargame that can remind us of this is a triumph in itself. The weight of strategy is just gravy.