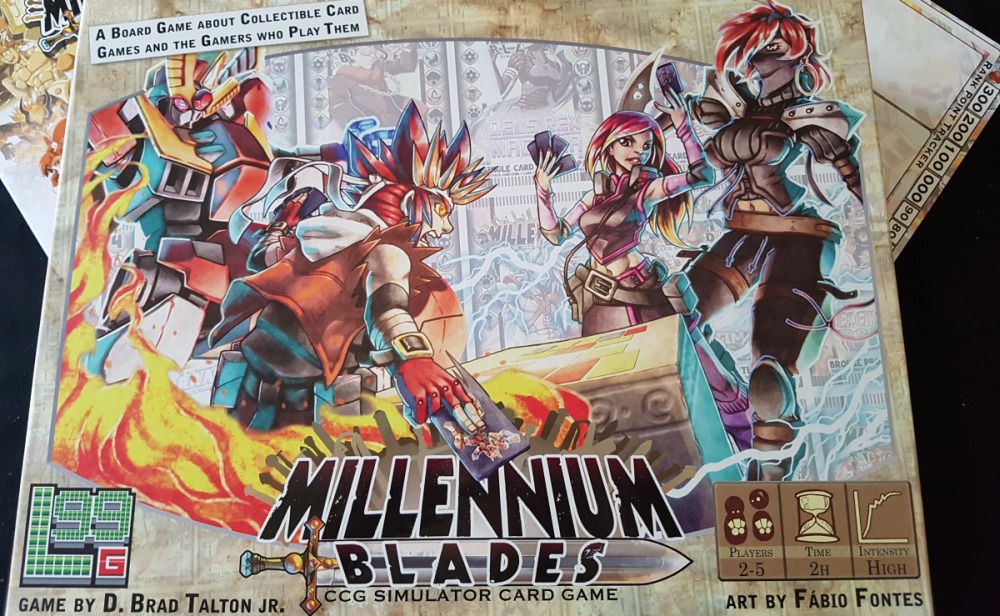

Thrower: The table is a wreck of cards, tokens and wads of cash. One player has collapsed on the sofa, eyes closed, exhausted. Another feverishly sorts their deck, cards held close to face, unable to understand what went wrong. Someone else has walked out, professing a desire for space and calm.

I’m wondering where the last two hours went and how I didn’t notice we now have an audience of a new visitor and a cat. I realise, suddenly, that on this cool spring evening I’m bathed in sweat. This is the aftermath of Millennium Blades.

We’ve spent the time pretending to be players of a fictional collectible card game in an anime universe. Millennium Blades is, then, a game about playing games. This sounds like a recipe for a design that disappears up its own backside. Instead, this game is interesting, intense and ingenious. Stuffed with self-referential satire, it sits, winking at its players from the comfort of its oversize box. If you can unpick all the parodies from a card called “I’ll Form the Head” from the “Obari as Hell” card set, you’re a higher voltage gamer than me.

(Click for bigger!)

You begin with a starter deck of nine cards, plus three random extras. All of the starter decks are similar, but with a twist. One, for example, tries to generate points by flipping cards face down. Another shuts down other player’s scoring opportunities. If you’re new to the game you play a tournament first, so everyone understands the rules. Millennium Blades also bans take-backs: if you make an error, you have to live with the consequences. No one will understand why this is necessary. Not yet, anyway.

Tournament play is simple. Each turn you play one card onto your play mat, eventually forming a line of six. Then, if any of those cards have action text on them, you can resolve one of those if you wish.

The aim is to collect as many points as possible. There’s lots of ways to do this. Each card has an anatomy including star rating, Type, Element, rarity, set and in-play effects. As well as flipping cards you can “clash”, which means comparing rating, plus that of a random card, against another player to see who wins. Other cards are reactive, protecting against flips or clashes.

There’s astonishing variety within this simple framework. Take the “Greendew Bazaar” starter deck. It contains a 1-star card that scores if no adjacent cards have a higher star rating. Makes sense, then, to play it first so it only has one adjacent card. But you’ve got another card that can swap the positions of two others, scoring the combination of their star values. So maybe not, depending on what other players are doing? One of your extra starting cards might be one that changes star values, helping you see how effects stack into interesting combinations. Other cards in the set score points for each earth or air Element card in your tableau or for having a variety of different card Types.

Once you understand the tournament, Millennium Blades hits you with the big bait and switch. The tournament isn’t the game at all! The real game is what happens after the tournament and before the next one: collecting cards.

Not just collecting, though. That would be too easy. The real game is buying cards, selling cards, archiving cards, getting promos, trading, making a deck and cursing loudly. Because you’re made to do all of these things at the same time… against the clock.

You’re given twenty minutes, which sounds like a lot. And at first, with your teeny starter deck in hand and thirty Millennium Dollars(!) in your pocket, it is a lot. There’s the temptation of some face-down cards to buy, so that’s where you’ll start. Each shows you the cost, set and rarity, but nothing else. What you get is partly down to fate and, often, it’ll be useless. So you snap up another.

Thirty dollars won’t go far, so soon you’ll want to sell some cards. But when you try and decide which card to cull for cash, it’ll hit you: You’ve got a lot more cards than you started with. You need to rebuild your deck before offloading.

You’ll want to rebuild each time you sell a card. You’ll want to rebuild each time you put a set of matched Element or Type cards aside as a “collection”, for extra points. You’ll want to rebuild after you’ve cashed in a bunch of unwanted cards for a powerful promo. And whenever you want to buy a face-up card that another player has for sale. And whenever you want to trade cards. And whenever the “meta”, which gives bonuses to certain cards, changes. All at once and all in real time and all the while knowing that one mistake, adding or removing one card, could be fatal to your whole enterprise.

That’s no exaggeration. In our last game the leading player ended up losing, by a whisker, because he’d misjudged a single card. The pivot of his strategy was a card he’d acquired that scored a ton of points if you had all six different Types and all six different Elements in your tableau. So many points he built his whole deck around it. But he’d only included five Elements and didn’t spot it until half way through his hand. His wife laughed so hard she almost choked on her tortilla chips before going on to take the game.

There are shades of Galaxy Trucker here, with everyone scrabbling for the best stuff at once. However, the race phase of that game can be a damp squib where you watch, helpless, as events cripple your ship. Here, you know you’re heading into a tight and interactive tournament. Plus, there’s much more going on in Millennium Blades, and it’s much less forgiving of mistakes. This is why the no-take back rule is important: it whips the pressure into a cardboard whirlwind, tearing your head apart. I don’t recall feeling so completely consumed during play since my first games of Space Alert.

Of course, not everyone is going to appreciate this. Most games which are punishing on the players offer them space to think. If Millennium Blades did that, it’d be a bitter soup of analysis paralysis. So if you don’t like the sound of one error made under intense pressure collapsing your whole strategy, this isn’t for you. Nor is it if you’re worried by the luck factor of buying face-down cards. The tournament is fun enough, but it feels a letdown after the thrills of the collection phase. And the apparent simplicity of the rules is deceptive. In play, you’ll find a lot of edge cases. That’s the last thing you want in such a frantic game, a sudden pause in the action while rules get consulted and everyone tries to reach a consensus. There is, inevitably, an enormous FAQ.

Against this one must balance quite staggering replay value. Each game uses a huge stack of cards, built from a mixture of sub-sets. It starts off so big that having your session obliterated by a clumsy player knocking it over is a real danger! Yet it’s only about half the cards in the box. You could rebuild that stack in any number of ways, each tilting the game in a certain direction. Each sub-set has its own theme and peculiarities that players can learn to gain an edge in card choice.

If that weren’t enough there are two pages of variants in the rules, plus a deck of location cards you can use to add setting-specific rules to a game. It feels like a game you could play forever, if you had the stamina.

As a middle-aged family man, I’m not sure I have. Millennium Blades has left me sleepless after every play, too wound up to relax. I could do without the stress that the game engenders.

But here’s the thing: it’s a sweet stress, a candied rush of glucose. Sugared by the way it satisfies the same desires as collectible games without the economic pain. Honeyed by the unique experience it provides and the wealth of play options. And just like real sweetness, it’s addictive. Sleep can be caught up on. Sweat washes off in the shower. So I’m going to risk another game or ten of this, because I’m an addict, and because you can’t put a price on this much creativity.