Paul: The Mind is one of the very best games that I have played this year. In the last twelve months. In the last twenty-four. Brace yourself, plant your feet, tense your muscles and tug that timeline back as far as you want and I think The Mind is still one of the very best games I have played between now and whenever. I have written so much about it and yet I still can’t communicate its gentle brilliance.

It’s also barely a game, not so much a skeleton of rules as a single bony finger, the sort that would be tentatively and timidly excavated, brush by brush, by archaeologists baffled by both its simplicity and its profundity. How, they might ask, could something so simple be so magnificent?

BUT FIRST, while your eyes were on that paragraph and your thoughts were lost in abstractions, I slipped a tether around your waist. HOLD ON, because I’m going to bungee us back to the distant date of May 2nd, 2018, to land right on top of my Decrypto review. Once again, I’m trying to explain how a game so simple is so terrific. Do I succeed? Not everybody thinks so. There’s a belief that seeing the game played would make it easier to understand. I wonder if this might be the case with The Mind, also a game of guessing, but also of one of entirely unspoken communication, a game of only expressions and exultations, of fidgets and feints. Maybe not, because so much of this game is played inside your head.

It presents two problems. The first is THE PROBLEM OF THE INTERNAL. The second is THE PROBLEM OF THE EXTERNAL. Imagine me stood in front of you, a blackboard behind me, onto which I have chalked the words PROBLEM OF THE INTERNAL and PROBLEM OF THE EXTERNAL. I am furiously tapping at them with my wooden pointer and I am also eyeing a boy that everyone knows is chewing gum right now. I push up my glasses. That boy has no idea what he’s in for. (And yes, you are still wearing the bungee cord. We’ll use that again.)

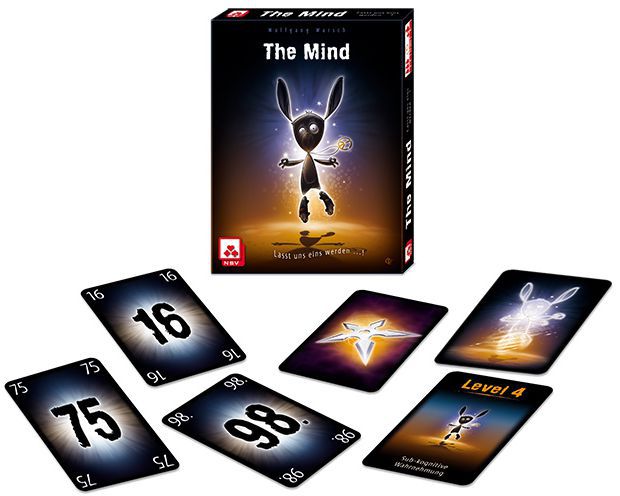

IT GOES LIKE THIS: Up to four players (and four is the magic number) are dealt one card per number of the round that it is, so one card in the first and two in the second and so forth. The cards are from a deck numbered from 1 to 100 and which has been shuffled into so much disorder. The players are not allowed to talk to each other and not allowed to show the numbers on the cards they hold, though they are free to stare at them, or at anything else, with as many of their eyes as they’d like. Someone has to go first.

The only thing the players need to do is lay all these cards down in numerical order, from lowest to highest. This would be easy but for one plain and simple fact: It… isn’t easy.

My pointer swishes across chalky text EASY to ISN’T EASY and raps angrily. A popping noise comes from the boy’s sagging mouth. A fly buzzes in the window. Are you paying attention? I push up my glasses again. Here is THE PROBLEM OF THE INTERNAL.

Without knowing what cards anyone else is holding, it’s impossible to know if you’re holding the lowest and should make the first move. Impossible, that is, unless you’re holding the number 1. Of course, if you’re holding the number 2, and particularly if it’s the first round and everyone is only holding a single card, you should probably go first. That’s only logical. Right?

Now, dear readers, I want you to extrapolate. Extrapolate far into the future, like a wiggly-headed Star Trek character with a name like Commander J’Pec. It’s round three, you’re holding a 6, a 17 and a 75. Is the 6 the lowest card anyone has been dealt, the card you should lay first? I’m going to introduce you all to a new word now, a word which bounces around your head like a squash ball in a salad spinner every time you play The Mind. That word is… Probablyyyyyy?

After all, you should probablyyyyyy lay your 17 after your 6, since the odds are that you probablyyyyyy have the two lowest cards that have been dealt, right? Yes? What would Commander J’Pec do? Probablyyyyyy the same thing. Anyway, it’s your decision. It’s not like you can talk about it.

Now here’s THE PROBLEM OF THE EXTERNAL, the conundrum presented by the existence of other people. All of those other people playing with you, right there, right then, are doing their own probablyyyyyy at the same time, staring at cards you know nothing about and, like the free-thinking actors they are, they’re all behaving independently! Oh no! Someone just laid a 2! But that’s okay! A 2 comes before a 6. They were right to rush in.

Extrapolate, Commander J’Pec. It’s round seven and we’re so much further in the future. You’re married now, with two kids and a mortgage that hangs over your head like a sagging shelf. But never mind that, you’re also holding the 34, 55, 61, 63, 88, 95 and 99. There are three others players holding a total of 21 other cards. Holding that 34, you can’t possibly have the lowest. You can’t play first. No. That would be madness. Surely someone’s going to drop a card. Any moment now. Any moment. What would the odds be that NOBODY ELSE is holding anything lower than 34? They’re… infinitesimal? Probablyyyyyy?

Bungee again with me back to the basics. Remember how I said The Mind insists that players do not talk? You have probably gathered by now that they also don’t play in any particular order. There is nothing to stop the person opposite you trying to go four times in a row, something that is probably a VERY FINE IDEA if they’re holding four sequential cards, but something universally regarded as NOT SO COOL if they’re laying down the 55, the 56, the 59 and the 61 while you’re fumbling the 58 and trying to force that thing into the playing order as if it were a pin back into a grenade.

How do you work out how to play The Mind effectively? That’s on you. That’s down to whatever non-verbal tics and twitches you can all express to one another, each one a hint that you think perhaps you should be going next, hints sometimes ignored by those rushing to lay because they’re so sure they have to go next, that they’ve got to act before someone else will beat them to it and wreck the order. A 28 should definitely be played after a 25, right? Probablyyyyyy…

Something happens to you all. You have all been transported to a strange space somewhere between hedonism and hesitation, a place where words have no meaning but where the tiniest of gestures suddenly start to communicate profound things. Someone lays a 30 and someone else leans back, their way of suggesting all of their cards are much, much higher and they won’t be laying any time soon. Probablyyyyyy. Suddenly, two players somehow mesh together perfectly, like titanium cogs, laying an almost sequential series of six cards. Or maybe you all silently orchestrate the card equivalent of a four-way tennis rally, card after card dropped with just the right amount of urgency and timing and on-the-fly probability calculations. It’s marvellous. It’s magical. It’s almost a mystery how you even did it.

Of course, you don’t get it right all the time. If someone lays a card with a higher value than one or more cards still held, those cards are dropped and a life is lost. Lose all your lives and the game is over. However, after completing some rounds, you’re awarded more lives and occasionally also shuriken. Shuriken, named for reasons that aren’t at all clear, are the cards that can save your neck.

Shuriken are played by mutual consent. If a player raises one hand, it means they want to use one and, if everyone else raises a hand in agreement, they all stop play and then each discard their lowest card. This is both a pause from the constant pain of everyone internally probablyyyyyy-ing to themselves and also a vital source of information. A shuriken lets you know just a little more about where everyone might need to be in the playing order and also shows you outliers. That person dropped a 90 while the rest of you were still in the 20s and they still have five more cards in their hand, so you know that they’re going to drop and end-game flurry and you’ll have to time your 95 with the accuracy of an atomic clock.

All right then, you can take off the bungee. I know you may have questions, the first of which might be “How is this a game?” I can only answer that it barely is, but it is exactly as much game as it needs to be and no more. It is the very simplest of exercises, governed by the thinnest of rules, and it’s smart and savvy and sublime. It creates a weird kind of telepathy that I’ve seen brew impossible chemistry between strangers and cause the closest of friends to be confused by one another’s actions. Or inaction.

One moment, it grants you strange new insights into people: Do they lay cards with timidity, or slap them down with all the confidence and panache of a luchador? Do they wait to watch their fellow players or do they throw caution to the wind? The next moment, it reduces you to animalistic utterances that transform you into a team of cavepeople as you “Ah!” and “Ooooh,” and “Urrrggh,” your way through another round, grunting and staring each other down as you reach for cards like cowboys for guns. It creates moments of soundless synchronicity unrivalled in gaming that make you feel like a ninja. Perhaps that explains the naming of the shuriken.

Does Shut Up & Sit Down recommend The Mind? I flip the blackboard. I lean forward. I push up my glasses and I point to a conclusion that causes the boy’s jaw to drop, his gum to slide out and his arse to fall off the chair: Honestly, I think everybody should play this. I think it’s both so simple and so smart that it will not so much smash language barriers as slide under them, unnoticed. I think it will take a lifetime to master. I think it’s a gateway game for newcomers to the hobby and something even the most crinkled of cynics will enjoy.

Somehow, there are few things in life more satisfying than laying down cards in the right order, something that gets the blood pumping through your veins in a way nothing else quite can, something that gives you the feeling of being a true hero, a feeling that you know few others will ever really experience in their lives. The Mind is one of the purest, simplest and best games I have ever played.

Two postcripts! One: At higher, harder levels, The Mind makes you lay cards FACE DOWN, meaning that you can’t see what anyone has laid until the end of the round, after which you hope you all did it in order. It sounds like it should be impossible and yet it isn’t… quite. Not least because the human brain has considerable capacity to probablyyyyyy its way through problems.

Two: We began every game of The Mind with a gesture. Nothing could start until we’d all placed one hand, palm down, on the table. That was our cue for silence and our cue to begin. Like everything about The Mind, it sounds simple and even insignificant. Also like everything about The Mind, its simplicity makes it wonderful.