Quinns: Alright ladies and gents. Today we’re tackling a box of unparallelled size and charisma. The publishers tell me that there are less than 3500 copies of Vinhos Deluxe Edition (the Kickstarted re-imaging of 2010 wine-making classic Vinhos) left, and I want to make sure that you guys have the chance to buy one.

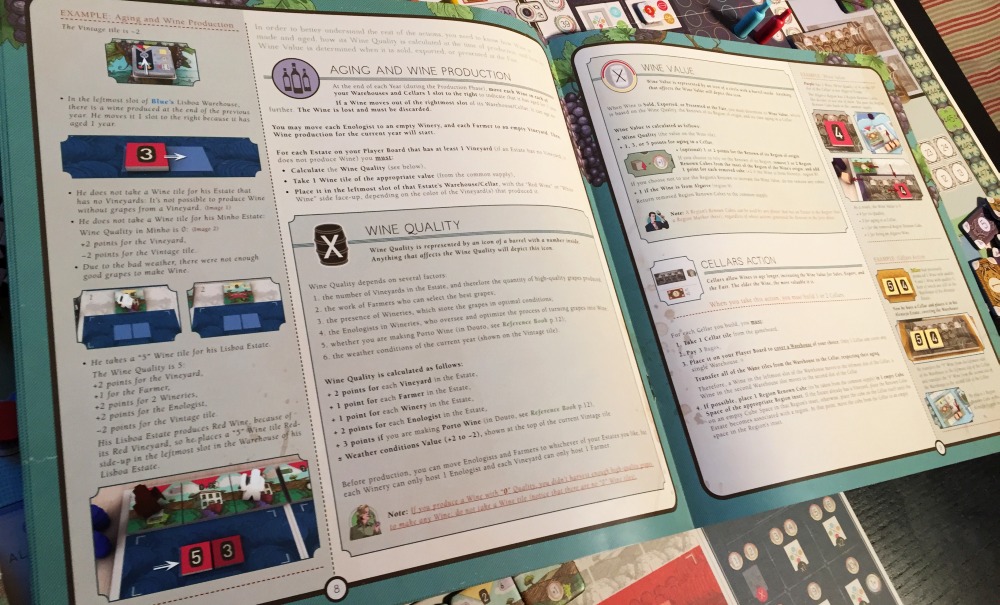

It takes a lot to excite me these days, but Vinhos Deluxe Edition managed it. Contained in this box is nothing less than a torrent of beautifully-illustrated tokens, a board that’s positively threatening in scale, and a fat, clean manual written with wit. It even has nice fonts! In a board game!

But it takes very little to make me nervous, and Vinhos Deluxe did that too. The rules that make sense, like buying vineyards or aging wines, contrast fiercely with the more arcane regions of the board, where players claim score multipliers or manoeuvre their action-selectors.

Any inference you want to draw from the header image of this article is correct. This game’s a beast to play, it’s tougher to teach, and it’s even harder to review.

Obviously, I couldn’t be more excited.

Laughably, before we begin this review I need to tell you which of the games in this box I’m reviewing.

Vinhos Deluxe Edition comes with a ton of extra tokens, two manuals and a double-sided board to let you play either the original 2010 game, or a simplified re-imagining called the “2016 Reserve”.

This article is a review of the original 2010 monsterpiece. Reviewing a simplified version felt like ordering a bacon cheeseburger, but removing the bun to dodge some calories.

SO YOU WANNA BE A PORTUGUESE WINE-MAKER!

In a sense (and literally only one sense), Vinhos couldn’t be simpler. The grid you see above shows the nine actions you can take on your turn.

On this turn (HERE WE GO) you’re going to move your little coloured wine baron to the action you want, paying €1 if you’re moving more than 1 space, paying other players €1 if they’re on that space, and paying another €1 if the game’s cylindrical turn marker is in that space.

Interestingly, the grid’s layout is such that whatever the most natural action for that act of the game would be, the turn marker is sat there. Like a scarecrow in a field, this ensures players’ strategies are nice and scattered. I love that.

Four of the actions you can pick continue the terrible lie that Vinhos is nice and simple. They are: Buying vineyards, building wineries, building cellars and hiring enologists (who are experts in Brian Eno).

All of these developments go on your personal board (seen above) depicting your wine estates, and do exactly what you’d expect. Each new estate you found will periodically produce a red or white wine token. The numerical quality of these wine tokens depends on how many vinyards, wineries and enologists that estate has.

BUT! All of your wine tokens slide one space to the right during each manufacturing phase, making room for the new wine you’re producing. That’s great if you’ve built a cellar since the wine will age gracefully and become even higher value. If you haven’t built a cellar and you’re just keeping the wine somewhere – I imagine it stacked up in your bathroom or in the back seat of your car – you could be in trouble, since after two manufacturing phases a token will fall off the track, spoil and become worthless poison Ribena. So you’d better do something with it before then.

There’s other stuff to consider, too. Wineries are expensive but each can also house an enologist, and each enologist massively improves your wine but has to be paid a salary.

Of even greater significance is where you choose to build each estate, since every single region of Portugal (see above) has a different benefit and cost, from Ribatejo, which gains you a farmer who can boost any vineyard, to Douro, which sporadically lets you make extra-valuable port.

Anything else? Oh yes, reader, there’s SO MUCH ELSE.

There’s the fact that each region has a stack of two red and two white vineyards for sale, but these stacks are shuffled, complicating the expansion of your like-coloured estates. There’s the fact that each time you buy anything you place a “reknown” cube in that region of Portugal, and these cubes can be spent by any two-bit grape-grabber who has an estate in the region to boost the value of a wine they sell, so players who invest in the same region of Portugal then race to divest it of its reputation.

Quickly claiming several low-quality estates across Portugal is a good strategy, since that means you can claim lots of regional benefits and produce more wine tokens, giving you flexibility. But then you become vulnerable to the vagaries of the weather tiles, and a particularly bad year could mean you produce level “0” wine, meaning you produce nothing at all. Presumably E.U. regulations mean that legally you have to label that year’s produce as “wine-flavoured drink” rather than actual wine.

In other words saying there’s “stuff to consider” is an understatement, and all of it is going to have you thinking in silence for minutes on end before you can take your turn.

Now, let’s look at two more of those action spaces you can visit on your turn: Either selling wine (for money) or exporting wine (for victory points).

Oh, did I not mention this yet? This isn’t just a game about making money. Money is just how you develop your estates. The winner is the most prestigious winery, which means either gradually changing the direction of your strategy throughout the course of the game or performing a screeching handbrake turn towards “POINTS!” as late as you dare.

The problem with either selling or exporting is that pesky economic concept of “demand”, represented by players filling spaces they fulfil with their barrels. So clearly you want to get rid of your wine before anyone else. “But my wine’s getting better ever year…” says the right side of your brain. “But I need money now!” says the left.

And speaking of money, let’s cover the banking action. The bank is one of the elements Lacerda chose to excise from the 2016 Reserve version of the game, and it’s laughably easy to see why. BEHOLD:

In addition to the “living” nature of wine as a resource, your money’s “alive” too. Everyone starts the game with not-quite-enough cash on hand that’s used to buy things, as well as a not-quite-full-enough bank account that’s used to pay salaries.

Because this is a game set in the sunny days before global financial collapse, everyone’s bank balance increases by €1 each turn, and in addition to depositing or withdrawing money from your savings account you can put extra spending money into the investment track and then get €2 every turn, or €3! Or you can divest and then lose money from your bank account every turn, but have more cash on hand right now to buy vineyards and make more wine.

Still with me? Fantastic. We’re almost 1,200 words in so let’s do the European thing and stop this rules-explanation-car in a field for a glass of chardonnay and a sandwich.

Let’s look at the big picture. The board game scene gets a hundred new engine-building games each year. So many of them seem fun and offer tough decisions, but so few of them stand the test of time. Vinhos is a game that clearly does have staying power, demonstrated by this beautiful new version. Let’s talk about why that is.

So here’s one funny thing: Vinhos is terrifying to teach. I’m exhausted from just trying to paraphrase it in this review. But what surprised me is that after teaching it, I never got any rules questions from my friends. The rules are knotted so tightly with the theme that it all sticks in your head.

And unlike, say, Brass, nobody ever feels lost. It’s obvious what you want to do – make wine, use wine, re-invest – and how much thought you put into your next turn is absolutely up to you. If you want to simply buy a cellar or sell some wine because that feels “right”, go for it! But if you want to mull over the probabilities of weather + the value/cost proposition of different developments + Bacchus only knows how many other factors, you can do that too. For such an intimidating game, it’s quite welcoming when you actually climb into it.

Maybe most importantly the engine you’re building is rewarding, and not just because these tiles and staff you’re adding to your personal board in the deluxe edition are so pretty. There’s a thrilling sense of escalation to Vinhos where the first barrel of wine you produce feels significant. The first batch of wine you sell brings a thick stack of cash. The first wine you lose due to mismanagement feels heartbreaking. The first truly great wine you reap seems to be overflowing with possibility, and you simply don’t know where to send it!

Because in addition to exporting and selling wine, you’ll also be shipping it to the game’s regular wine fair:

…And this is where we get into the stuff about Vinhos I like less. So far the game we’ve described has been fairly simulationist, evocative and memorable. It’s been a smooth ride. NOW we’re climbing back into the rules-explanation-car and I’m going to drive far too fast down a rocky country lane. Imagine that one tunnel scene from Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory but with wine bottles clinking sharply in passenger footwell.

The following three paragraphs will be no fun. Just buckle up and we’ll get through this together.

At three points during the game everyone sends a wine to Portugal’s wine fair, and the quality of the wine you send doesn’t matter as much as the “wine expert” tiles you can discard to improve your standing with the judges. This is relevant because the score you get at the wine fair isn’t reset each year, so winning the wine fair also puts you in good standing for the next one.

Shopping for wine expert tiles is one of the other actions you can do on your turn along with buying vineyards, visiting the bank and so on, and in addition to being spent at some fairs to improve your standing (depending on whether their colour matches the colours on the the weather tile that shows that year’s wine fashions), each wine expert can be spent for a special bonus (like moving your action selector without paying money) and becomes available again after each wine fair.

Finally, the wine you send to the fair has to also please Portugal’s three wine magnates (pictured above), Anabela, Bruno or Carolina, who are all looking for different things depending on the weather tile. Getting in good with these desperately important people gives you access to extra moves(!) and score multipliers(!!).

In other words, Vinhos’ previously sensible and charming world of wine and money has a dark side that players must also wrestle with, a Mordor of changing fashions and clauses and iconography. I’m being a touch melodramatic. This other half of Vinhos, the whims of fairs and magnates, is fine, and it’s certainly as tough a puzzle as everything else in the game. But it’s also where Lacerda and I part ways in terms of design philosophy.

It’s clear from both Vinhos and Lacerda’s later games, like Kanban and Lisboa, that this is a designer more interested in making sprawling, multi-faceted clockwork enigmas than he is in making something cleaner. As a result, parts of Vinhos feel to me like complexity for complexity’s sake.

I’m not saying I’d want Vinhos to be simpler, just that the concepts of wine, staff and money as unstable resources could have been expanded on, since they’re unquestionably the more entertaining side of the game when compared to cross-referencing what each magnate offers, with what they want that turn, with what wine you have. Like Portugal, it seems that not all regions of Vinhos were created equal.

Overall, though, I really do like this game, and I’d play it again in an instant. Here at SU&SD it’s all too easy to recommend games that are fun for a month. If you’re a fan of engine building, Vinhos Deluxe feels like something you could explore for years across 10, 20 or 50 happy evenings, and that’s backed up by the game’s existing fanbase.

I keep coming back to how little choice you have on a turn. It’s startling, really. There are nine action spaces and on your turn you just… pick one of them. You do that twelve times and the game’s over, which means that while this game is exhausting to teach it’s a comfortable thing to settle into, like a rocking chair on a sunny porch.

So much of vinhos is pleasant stuff that you sit back and enjoy. Wine will age, your friends will comment on the nuances of wine making, competitive whippersnappers will compete at the wine fair, and you? Why, you’ll happily play your part in this grand old game. Move a piece here, slot in a tile there, slide your wine along. If Lacerda’s built an utterly mad clockwork engine there’s at least the sensation that it’s an efficient one. You give it the slightest of pushes and the friends and tokens and hopes and dreams go spinning around you, like stars overhead. Better still, your opening moves – where to invest, whether to go for one super-estate or lots of small ones, even how many friends you play with – leads to a game that feels vitally different.

In essence, Vinhos an intriguing, complex game with a touch of the breeziness of a simpler one. It’s a rich red wine drunk by the sea, with a salty breeze when you lower the glass. It’s a little bit magic.

And actually that doesn’t surprise me, because even as I was learning it I was shocked to find I was reading one of the greatest manuals I’ve ever encountered. Like Van Halen’s legendary contract including a bowl that contains no brown M&Ms, this is relevant not just because a manual is important, but because it hints as to how much care went into the rest of the game.

With that in mind, the manual’s just unparallelled. It’s beautifully illustrated, the writing is clear, there’s careful use of bolding and underlining to reliably catch your attention, there are clear examples for every single rule, and the tone of the writing isn’t just friendly, it carefully preserves the heart of the game, imagining the reader not as a player but a new business owner.

The box has a great inlay, too. Go figure.

(Ignore about 25% of the stuff in the below shot. They’re Kickstarter extras that you won’t get with a retail edition of Vinhos Deluxe, but don’t worry about that. The expansions aren’t hugely exciting.)

I just went and made myself a cup of tea, taking a moment to think about what conclusion I wanted to put on this review.

This led to something of a realisation. All too often SU&SD talks about games in terms of “good” and “disappointing” art design, of game mechanics that either succeed or don’t.

Maybe the most important line in this article is my point that Vinhos never fails, it simply deviates from what I would have wanted. Which means, more than anything I’ve played this year,Vinhos Deluxe feels like art. It might not be perfect for me, but it feels like a perfect exhibit of the author’s intent. Like something I could hold up in both hands (this is a big box, after all) as everything that board games can strive to be.

That’s quite the success. This game might not be for everyone, but if it is for you, don’t let it slip you by. Stock availability looks best if you order direct from Eagle-Gryphon Games.