Hilary: Lately I’ve had Burning Wheel on my mind.

Some friends recently started up a streamed campaign with Roll20, and I tuned in to watch all 4 hours of their character creation. I joked around in chat, explained bits of the rules and mechanics to people who asked, and generally had a great time. But I haven’t been watching them actually play. I’ve stayed away partially because the timing doesn’t quite work for me, partially because one of my roommates is in the game and I can hear him talking in real time and then again 10 seconds later via Twitch’s time delay, but, most of all, because I am way too jealous.

Burning Wheel is one of those games I’ve played just enough to fall in love with, but not nearly enough to be sick of. Or even remotely satisfied.

What is the Burning Wheel? It’s a roleplaying game first and foremost about characters. Realistic-feeling, rounded characters, with talents and flaws, ambitions, goals, and dreams. It’s a game about watching a story unfold and develop around you, about learning new skills, challenging your beliefs, failing, getting yourself into trouble through your own over-ambition and mistakes, and growing as both a character and a player.

Burning Wheel is an incredibly mechanically-rich game. I could spend a whole review talking about the different moving parts. Two reviews. A 600 page book. But instead, I want to focus on how the game feels.

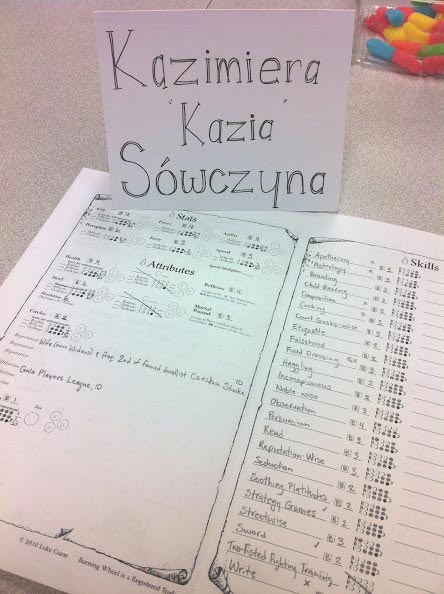

In every campaign-style game I’ve played there’s at least one player who comes up with an incredibly detailed backstory for their character. They’re stoked to share that information with the table, and generally other players are interested to some extent, but the game itself generally does not care: there are few if any mechanical consequences of their character’s life up to the moment the game begins. Burning Wheel, by contrast, not only cares, but relies heavily on the various details of your character’s life-‘til-now to provide mechanically-relevant skills, social connections, personality traits, material possessions, and more. Your character’s backstory isn’t some optional frosting on the RPG cake, it’s an essential ingredient, baked right in.

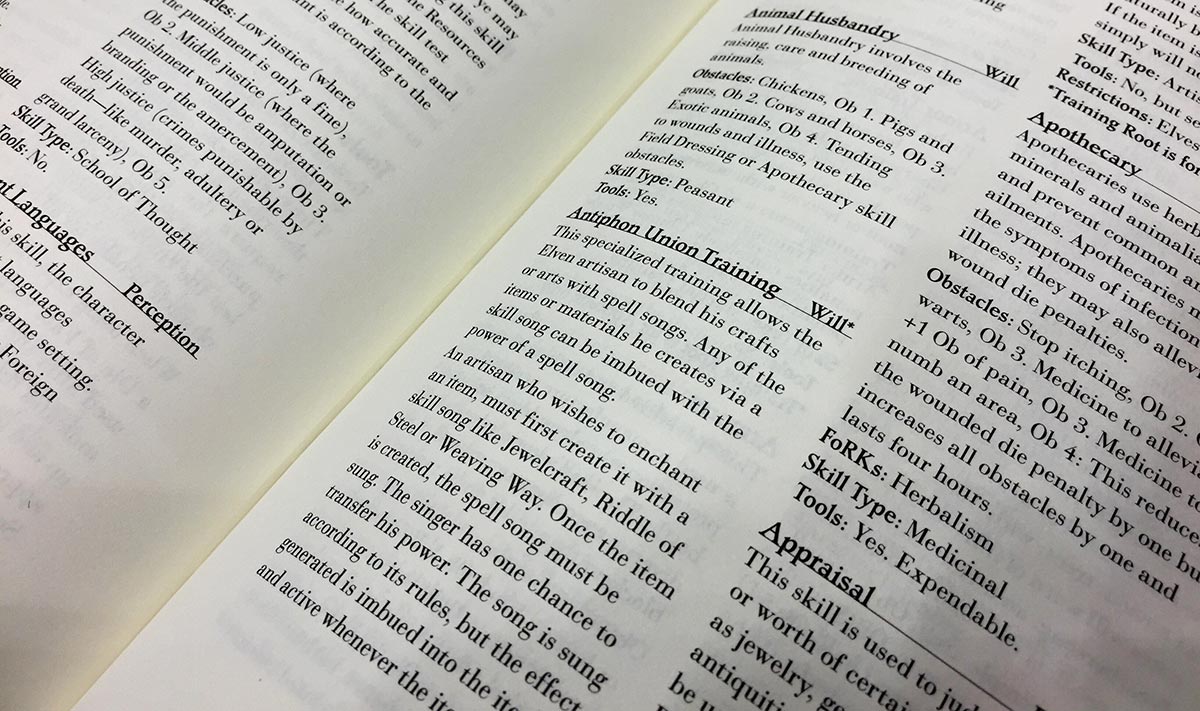

Burning Wheel encourages roleplaying not just theoretically, but mechanically. Your character’s skills have evocative names that give depth and interest to the ways you interact with the world. The game asks each character what they believe, and what they’re specifically going to do about or because of that. Characters each have a few things they do in certain situations without even thinking about them—sometimes to their narrative benefit and sometimes not so much.

If it exists as a skill and your character doesn’t have it, they straight up have never attempted and do not know how to do that thing. Don’t have Read? You can’t read. Don’t have Brawl? You have no idea how to brawl. But you can always try!

Attempting things you don’t actually know how to do yet (and generally failing a solid portion of the time) is how we learn. And it’s how your character learns in Burning Wheel.

The game rewards you mechanically for taking on challenges, getting yourself into trouble, and working towards your goals. That trait or instinct that got you into trouble narratively benefits you mechanically, eventually providing opportunities to triumph in otherwise impossible situations. Playing it safe and only doing things you’re good at won’t get you anywhere in Burning Wheel. Sure, you’ll stay alive—boring and stagnant.

Maybe I should take a moment here to say that I love, LOVE playing characters who mess up. I love trying and failing and getting into trouble and encountering the unexpected. I think things are more fun when I don’t feel assured of constant success.

Now, don’t get me wrong I like succeeding, too! I like working with the other characters in my party to overcome obstacles, and plot and scheme ways to accomplish our goals. But, to me, there’s something much more satisfying about overcoming those obstacles and accomplishing those goals when they don’t feel certain.

Playing a character who’s super powerful and great at everything and never gets into trouble no matter what comes their way can be fun, perhaps, for particular, very short-lived games. But those aren’t the characters I root for. I don’t feel compelled to stick around and see what happens to them.

In Burning Wheel you’re near-guaranteed an interesting, fallible, compelling character. And if, somehow, they didn’t start out that way, they’ll quickly begin to reveal their faults and quirks through play.

Burning Wheel is also a game that encourages players to grow in skill along with their characters. When you first start playing it’s easy to feel really overwhelmed with all the moving pieces. Over time, though, you get the hang of the core mechanics and are able to introduce more and more advanced aspects of the game. It’s one of the few roleplaying games you can actually, markedly feel yourself get better at.

You can tune the Fantasy Dial up or down within Burning Wheel, depending on your group’s particular tastes. But no matter how high you crank that Fantasy Dial, it will still be a game about characters who grow through challenges and failures, not a game of perfect heros.

This also means the nitty gritty of daily life is much more interesting because Burning Wheel actually supports you playing it out. (While also imposing a tidy limit on how often the mechanics are engaged in pursuit of any one immediate goal.)

Your skills—or lack thereof—are just as relevant when trying to cook your party a meal as they are when trying to outsmart a guard or find your way through a forest. You can resolve conflicts and interact with the fictive world in all the nuanced and varied ways real people do. Violence is not the answer to every question, and playing the game as your typical, marauding, D&D murderhobo will likely just get you killed.

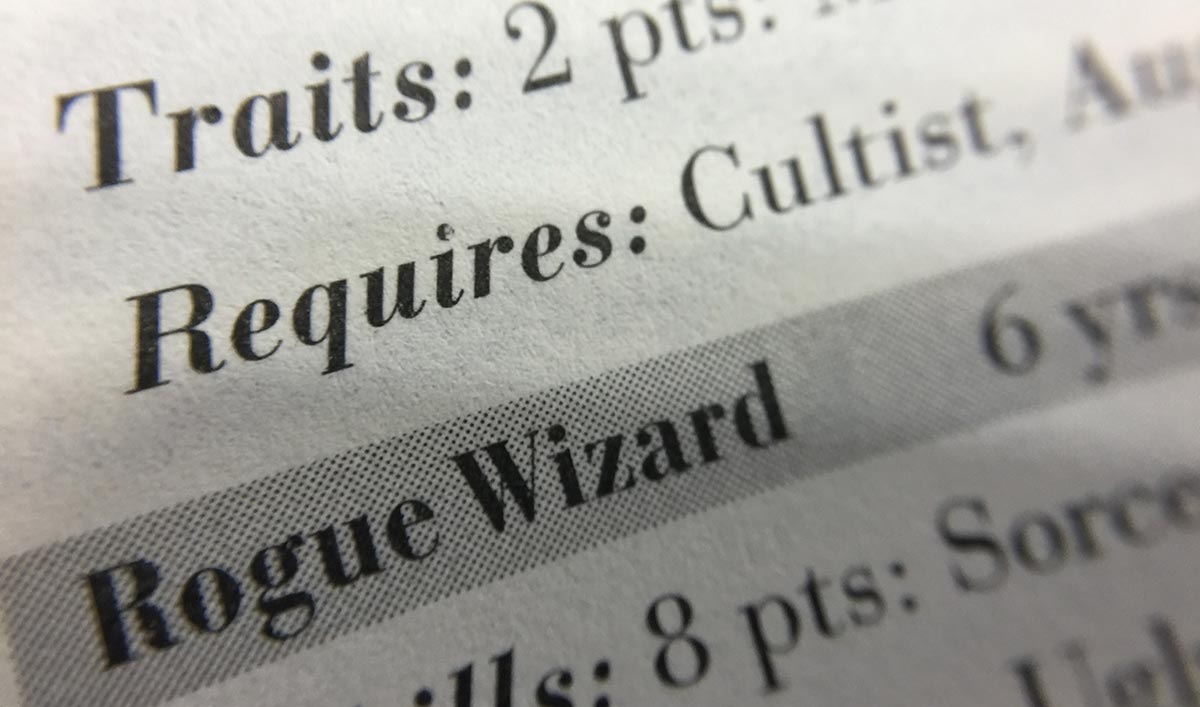

You can be a dwarf or elf or orc or human. You can have access to magic, maybe, if you’re lucky, and non-humans are frankly much better at most things than humans are. So, while you can have a mixed stock party, playing a humans-only, low-to-no magic game is also a really solid, satisfying option. In fact, I think the system really shines as a venue for low-fantasy roleplay.

I’ve heard people bristle at this, throwing around words like “balance” and “fantasy is about magic and I can’t believe anyone would want to play a game without a magic user in their party,” and sure, if those things are critically important to your fun, maybe Burning Wheel (or at least my preferred flavour) is not the game for you.

Burning Wheel doesn’t strive for an arbitrary “balance” in terms of characters, conflicts, skill sets, or anything else. Life’s not fair, some people are more skilled than you, there’s plenty of stuff you have no idea how to do, and if you get into a conflict where you’re clearly outmatched, expect to lose.

Finally, some notes on play style, group size, and commitment.

Because of the style of play, the game works best with a focused group of 3 to 5 players. You can scale some games up for much larger groups, but it just doesn’t work well here. (Trust me, we’ve tried.) Expect to have a lot of play featuring a few characters at a time, and be willing to pay attention as a group and support those spotlights. Your knowledge of other characters’ development and growth has mechanical implications for everyone involved.

Suicide Legion character portraits by Emily DeLisle (www.emilydelisle.com)

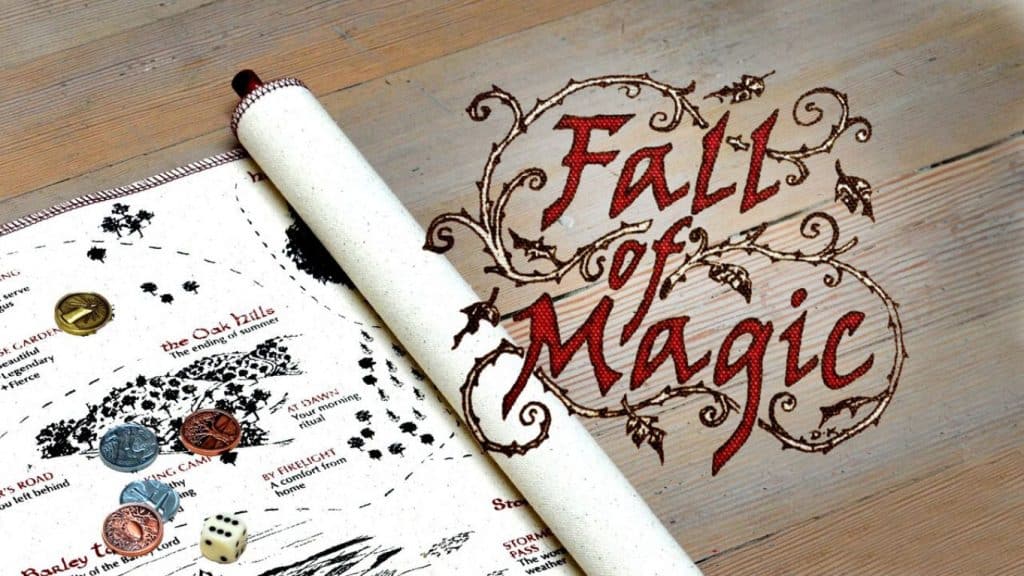

Some indie rpgs are designed as one-shots. You sit down at a table, make stuff up with your friends for a few hours, and then it’s over. (Kaleidoscope is an example of one of those games, though there are many more.) The commitment is similar to most board games, and, as with board games, the replay value is often high.

There are also games that aren’t designed as one-shots, but can be played as a satisfying single session, say at a con or a local gaming meet-up. I tend to think of those like pilot episodes for shows that were never picked up. They stand on their own, and are enjoyable, but you can tell they would really have flourished given a full 6 or 12 or whatever sessions/episodes.

Burning Wheel is neither of those types of games. To really get into Burning Wheel means commitment. You can’t really play a single, stand-alone session of this game. It needs time for characters to grow and change, for everyone at the table to become familiar with and eventually master the mechanics.

You can still have a really great time, as I have, creating characters and following their story for a few weeks, if that’s all your group can muster. But you will definitely feel like things have been cut short. This is a game of grand narratives, where we follow the small cogs and gradually become aware of the ways they fit into the much larger machine. For the full experience, expect to set aside at least 6 months of weekly sessions.