[SU&SD’s coverage of the growing, amazing story games scene has ranged from sporadic to non-existent. Introducing Hilary McNaughton, a writer and gamer from the land of “Canada” who’ll be helping us out with regular reviews! Please give her a warm welcome.]

Hilary: I don’t watch a ton of movies, so I generally assume if I’ve seen something, everybody’s seen it. But it turns out I’ve watched a higher-than-average number of weird foreign films. I’ve even seen a couple I just did not get. At all.

Maybe you know the kind? Things start out sort of intelligible, then dissolve into weird symbolism and visual effects about halfway through. Or there’s no plot, at least that you can find. Or everything seems normal, except for some reason the director shot the whole thing from a bird’s eye view and you never see anyone’s face.

Sometimes the very best thing about a film like that is picking through it afterwards with your friends. What was with the giant hand in the background of that scene at the park? Why didn’t anyone in the movie comment on the fact the sets were obviously all made of cardboard? Did everyone hate the long shot inside the revolving door, or just me?

Kaleidoscope is a game that brings you all the joy and frustration of discussing an opaque foreign art film, without actually having to sit through one. You and your friends invent the details of a fictitious movie in the same time or less than it would have taken to watch.

But how? you ask. I’ll tell you how!

Kaleidoscope (by Jackson Tegu) is a film-focused hack of Microscope (by Ben Robbins). The original is a timeline-building game, where players zoom in and out describing macro- and micro-level action. While Microscope can construct any timeline, grandiose or humble, Kaleidoscope takes that exploration of scale and twists the framework, ever-so-slightly, to reliably toss out a colourful mess of an art film. Coherent plotline certainly not guaranteed.

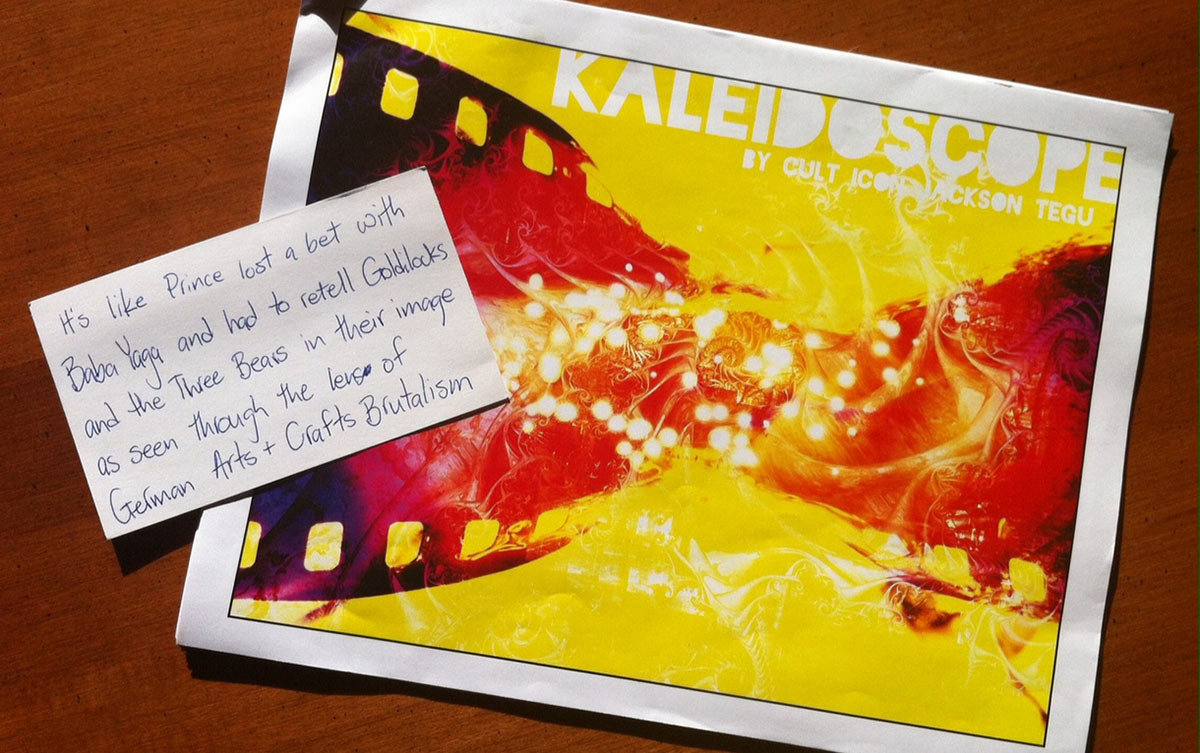

Sitting down with the rule booklet, the neon clash of colour on the cover gives you a taste of what’s to come. But while the cover image and resulting film may be esoteric, the game text is incredibly user friendly.

The reader is greeted with a conversational, step-by-step guide to setting up the game. There are suggestions on recruiting players, notes on pacing, and a detailed listing of all necessary supplies. After that initial set-up page, all rules are read together at the table (though both Tegu and I strongly advise whomever’s hosting/facilitating have a good read-through in advance).

The text does a decent job of setting the tone for the game while it teaches. ‘Cult Icon’ Tegu, as the cover proclaims him, walks us through the minutiae, making gentle jokes at our expense, providing dialogue for us to read, noting that while we don’t need to know anything about movies, “it can be helpful to have seen one”—subtly coaxing out our own genial inner film snob.

The game is meant for 3-5 players and runs ~2 hours, often less. The most recent time I played, the three of us spanned the gamut of indie-RPG experience. Daniel has been playing these sorts of games basically since people started making these sorts of games, and had already played Kaleidoscope a few times. Spark had never played any game like this before. I fell somewhere in the middle.

Going through the text, Spark remarked a few times how beginner-friendly the instructions felt. We followed each step and shortly mad-libbed the recommendation we’d received, checked out each other’s facial expressions as we “watched” the movie, and began to reminisce.

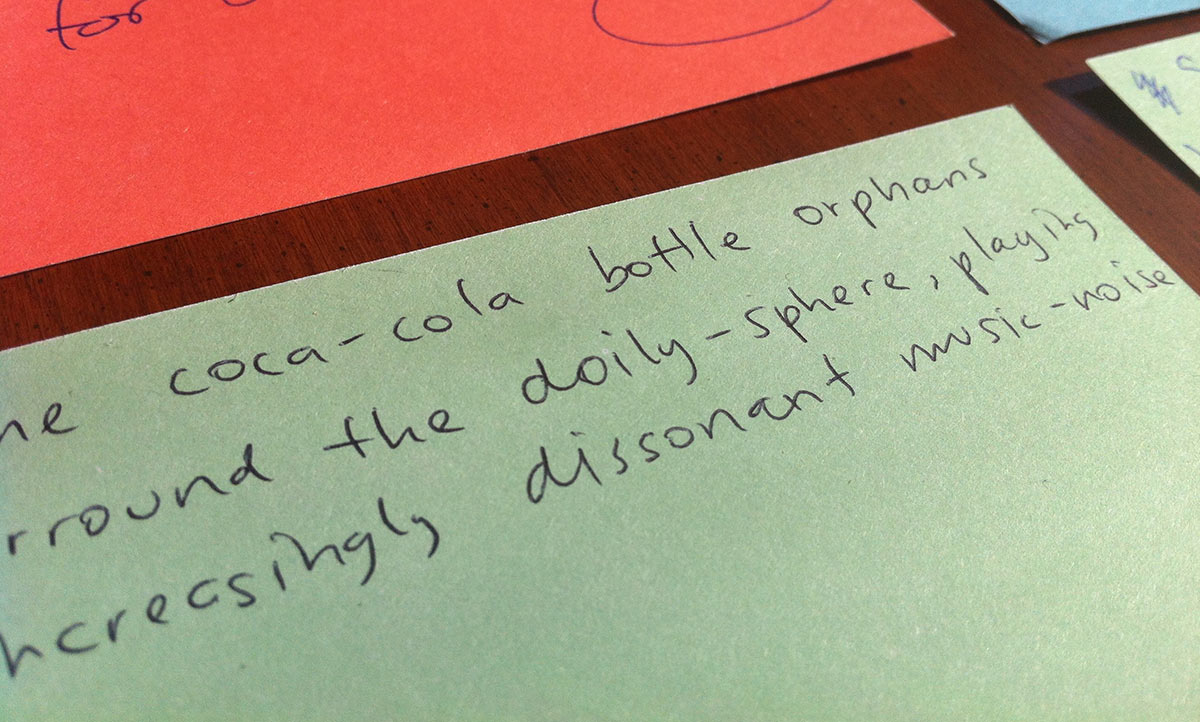

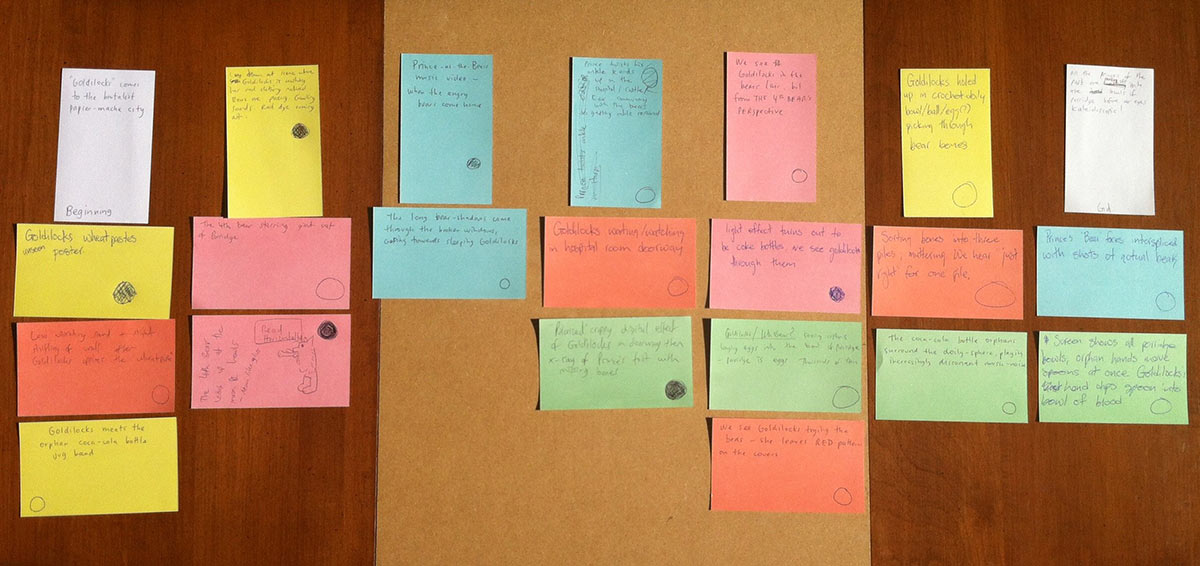

This is where the game really starts: someone ‘remembers’ how the film opened and someone else ‘remembers’ how the film ended, providing our bookends. A player invents a Lead from the movie, tells us their name, and gives a brief description. We then take turns remembering Parts (15-20 minute sections) or Moments (single beats or transitions) of the movie involving that Lead and adding those to the timeline of our film, noting whether we liked or disliked them. Then we talk about another Lead, and add parts or moments where they featured.

Before introducing the fourth Lead, pause to see if everyone feels one last round will be sufficient. If not, decide how many more rounds you want, adding the necessary supplies to the table. (We decided to add one more.)

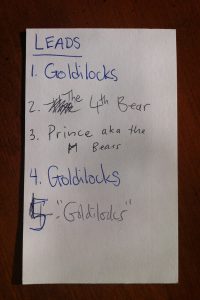

Once you’ve finished adding Parts and Moments to the film, everyone picks a different version of the title to present, writes theirs on a card, we share those, have a good laugh, and the game is over. Simple!

From top to bottom: what one projectionist put on the marquee at their small art house cinema when they ordered a print from the original studio, the direct translation of the original movie title, and the cultural translation for the limited DVD release.

That’s all there is to it? Yes and no. As the game text points out, Kaleidoscope really comes alive in the table talk. In its largest departure from Microscope, this isn’t just a game about inventing bits of a fictional movie and stitching them together, this is a game about the experience of discussing a film you all just saw. What did you like? What did you hate? What did you not get at all? It can feel a little wooden at first, but as the game goes on it becomes easier and easier to theorize on the symbolism the director was going for, or pedantically explain to your friends what that live bear cameo REALLY meant. You discover connections none of you planned, create some running jokes, argue over the artistic merits of this and that, and, at the end, have a film that feels almost as real as if you’d actually watched it.

So. Let’s get down to it. Should you play Kaleidoscope? It depends! There are things about it I think are fantastic, and I’ve had (several) great times playing it. There are also things about this game that are challenging, and I don’t think it’s necessarily suited to all audiences.

The text is great. It guides you from set-up into actual play, almost without you realizing. This is something carried over from Microscope, though Tegu also has solid experience crafting rules that teach at the table, as in his influential (and perennially unpublished) indie classic Silver and White. Are there some things the rules skim over or miss? A couple, but I’ve included my own suggestions to deal with those, below.

Kaleidoscope’s simplicity, pared-down from even Microscope, is both a strength and a challenge. The mechanics are easy to learn. If they don’t feel intuitive at first, you’ll likely have them down by the second round. That said, they are a sparse scaffold on which to build your film. They don’t get in the way, but they also leave virtually all the creative heavy lifting to the players. That can be fun, but if you’re shyer, less experienced, or not feeling confident in your ideas, it’s easy to overthink or get overwhelmed. Spark, for instance, enjoyed the game but was definitely experiencing creativity fatigue by the end.

All that said, this is a solid one-shot, which makes clear promises on what it will do, and delivers! I like it, and you may too.

Hilary’s tips for Best Play Experience:

- I usually give a brief pre-gaming talk when facilitating a story games session with any new(er) players, going over some tips/tricks/techniques people may find useful. As the Kaleidoscope rules include a lot of the stuff I put in pre-game chats, I skipped it this time. Talking with Spark afterwards, I wished I’d mentioned Reincorporation and emphasized Stating The Obvious when that was brought up in the text.

- The “recommendation” step is one of the only times we’re given creative material to build from. It’s also the first decision of the game, the only collaborative decision, and presents many options. It’s easy to get hung up here! I suggest guiding the group to first narrow down the templates, then work on filling in the blanks.

- Spend some time on the differences between Parts and Moments, as it’s easy to blur the two and attempt to do everything at once! Also clarify that the Beginning and End are both Parts—that’s explicit in the visuals but not in the text itself.

- The game text has visuals. Use those! Make sure everyone gets a chance to see how the game will be laid out, as that may help them better understand the mechanics and how it’ll all come together.

Quinns: Hilary that was eerily professional. Get some rules wrong next time, ok?

Hilary: Ok!

Quinns: Can you tell everybody a little more about yourself?

Hilary: Sure!

I’ve always loved writing. I read a lot as a kid, and am one of those people who’s a natural editor. I did some creative writing growing up, and took a writing-heavy track through school. Over the past 5 to 6 years my writing has been developing in two distinct directions: one creative, one more technical. My longest-running outlet for creative writing has been a smut blog focusing on human emotions and connection (the patreon is safe for work, but the contents of the blog are not).

In terms of technical writing, I’ve realized I love explaining things to people in helpful/humanized ways. I’ve used this skill for various employment/personal interest projects, and now I’m stoked to put it to use reviewing games! I’m also the undisputed queen of email composition, and can do a surprising amount of emotional labor in written form.

I didn’t play RPGs growing up. I had friends who were into D&D or Vampire, but no one invited me to play, and I figured it was some complicated thing I wasn’t qualified to try. I’ve always loved story telling and making things up with friends, I have a background in theatre and improvisation, and I sort of suspected I’d like roleplaying games. But I didn’t know how to get into them, or if I was Good Enough in whatever ways I might need to be. Three years ago my best friend (Adam Koebel, the biggest nerd I know) invited me to be part of a game of Dungeon Crawl Classics he and some friends were just starting up. I was nervous, but it wasn’t nearly as tricky as I thought it might be, and I was hooked! (I played every Friday night with that same group until a month or two ago.)

In August of that same year I reconnected with Monsterhearts’ Avery Mcdaldno, now one of my closest friends, and she introduced me to small press indie gaming. I started going to public story games events in Vancouver and elsewhere, playing ongoing games with friends, and attending Go Play Northwest (the major indie gaming convention in my region). I co-founded Terminal City Story Games, which ran weekly and then monthly indie gaming meet-ups until late fall 2014. I also facilitated at Games on Demand at PAX Prime in 2013. I’ve played a lot of games, playtested a lot of games, and even edited one or two. Making things up with friends and strangers has brought me a lot of laughter, provided moving and unexpected experiences, introduced me to wonderful people, and guided my imagination to new heights! I’m really stoked to share this loose genre of games with a new audience!!

Quinns: <3