Leigh: Hi, Shut Up & Sit Down-ers (the Silenced & Seated?)! Thank you for having me back again as your ongoing indie RPG correspondent. Quinns, I think something might have gone off in your fridge, though. What is that?

Quinns: My flat has an Abundance of Rare Meats, but a Scarcity of Hygiene.

Leigh: A reference to the game mechanics, how clever!

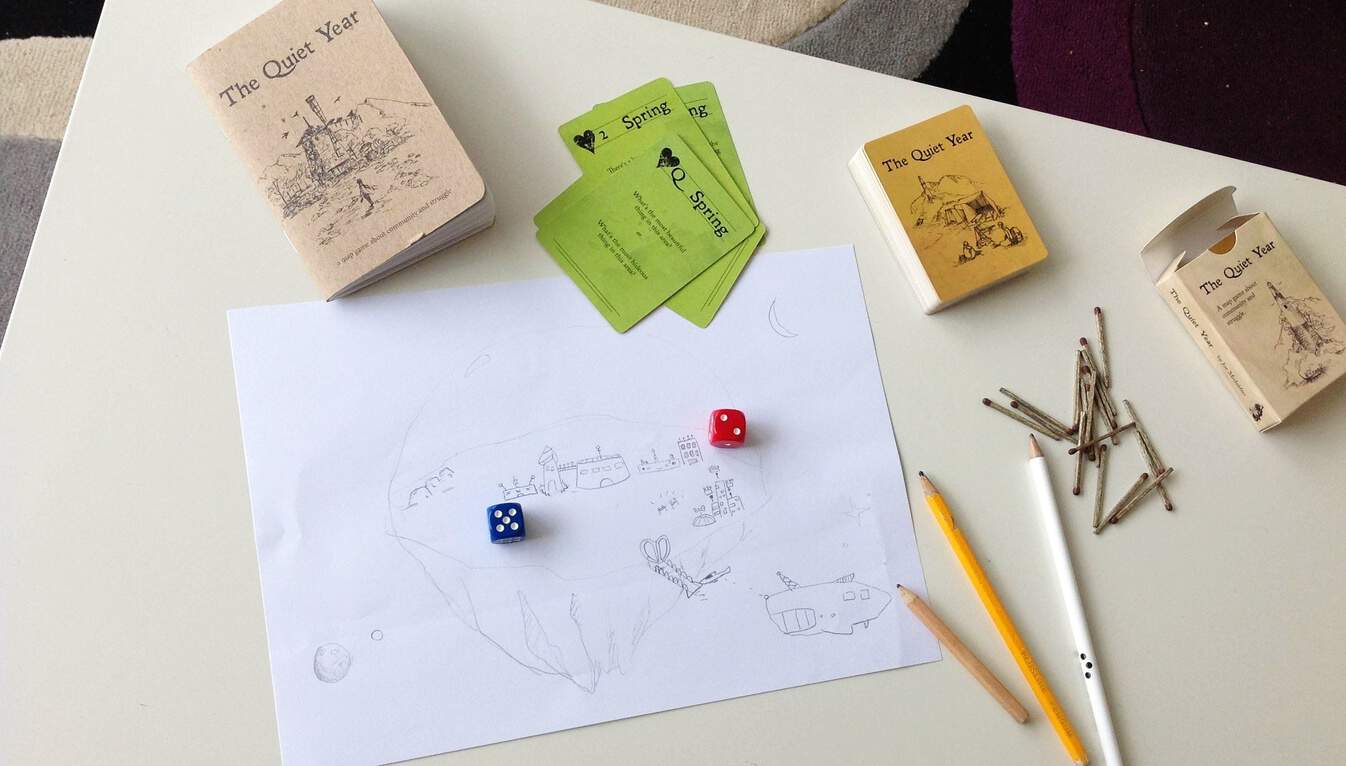

So, The Quiet Year. I’m accustomed to roleplaying games that give me the chance to tell a story about a character, through interaction with other characters, but this game is different: Two to four players collaborate over a map to tell the story of a place, and the narrative that unspools itself is about the challenges a community faces following a long war, given one year to prepare for the advent of the mysterious Frost Shepherds.

What are the Frost Shepherds? Who knows! What is this place? Well, that’s what you play to discover. The designer, Avery Mcdaldno, calls it the world’s first cartography RPG.

Quinns: Which, if you’re as bad at drawing as I am, is a terrifying prospect.

Leigh: You don’t have to be a good artist, fortunately. You can make little symbols. A square with a triangle on it could be a building. You also cannot handwrite on the map — it should stay a collaborative place built by images only — which is good, because your handwriting is concretely frightening. Want to tell how it works? The game, not your stilted frankenscrawl.

Quinns: Hello! OK. To begin with, everyone draws one feature onto the map. Perhaps you’re next to the forest, or in an inner city, or your community (strictly of some 80 people unless otherwise specified) lives in abandoned cruise liner.

Everyone then names one resource. That could be “drinking water” or “weapons”, but it could also be as thought-provoking as “children” or “joy”.

Leigh: The first time we played, you elected “performers.” You were probably trying to be silly and louse things up, but ultimately the community’s ritual of telling stories through performances given by children turned out to be an important part of the story. And I got to draw a lot of tents with flags, and lights, and it was really pretty.

Quinns: I was being serious! Anyway, all but one of these resources is then listed as scarce, and the other one is abundant. The game then begins, and The Quiet Year lurches awkwardly into action, like a foal learning to walk. I’ve roleplayed samurai, diplomats, the dead, the young, but nothing is as counterintuitive as what The Quiet Year asks of you.

Leigh: I think “counter-intuitive” is pretty harsh. It does feel like an open, unbounded possibility space, where a lot of the work of interpreting the rules is put upon the players. But then, I think that’s potentially… kinda nice, for a game about communities. Before we get ahead of ourselves, let’s explain the cards.

Quinns: Right. The Quiet Year is a strictly turn-based game, with everyone drawing a card on their turn, one for each of the 52 weeks in the year.

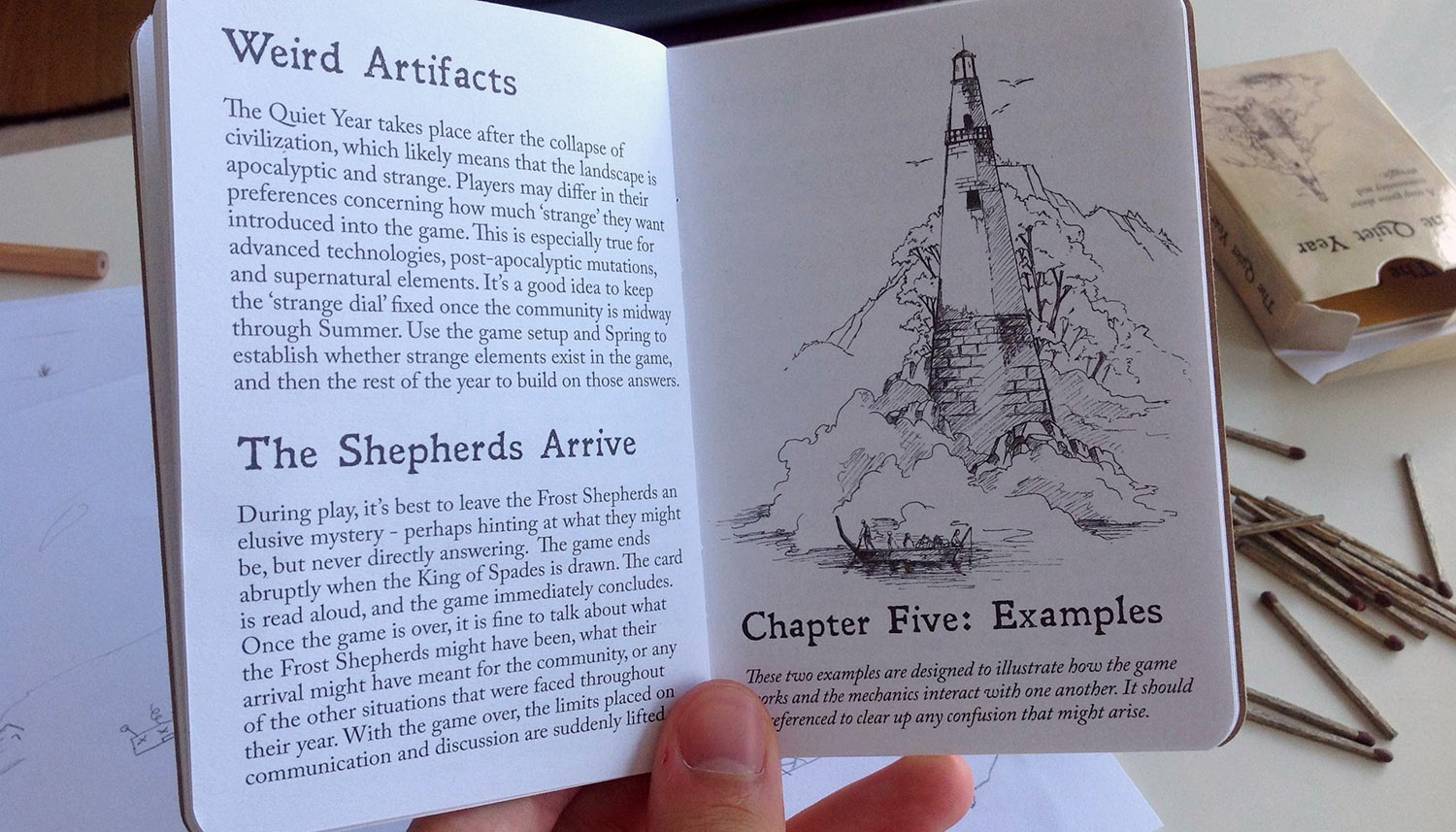

This card will ask something of you, and what’s wonderful is the different flavour of each season, giving the game four acts. Spring asks questions about your community. Summer introduces nuance. Autumn is a season of decay and strife. Finally, Winter is the wildest and most unpredictable month. The game ends whenever someone draws the king of spades — you can never assume you’ll get a full Winter’s play, as the Frost Shepherds could arrive at any time — but every other card is a sort of wild weather, alternately seeing your community being set back and coming together.

On your turn you’ll draw this card and do what it says, forcing your story, and your community, down unexpected avenues, and then after this you have a choice: Start a project, hold a discussion, or announce a discovery.

Leigh: Projects are things your community decides to build or repair — a hospital, or, say, a cannery to address fresh food scarcities. You add things to the map, then decide among yourselves how long they ought to take, from one to six weeks, and each turn you keep track of the progress by counting down with a die. The only time you and the other player can really discuss shared goals and priorities (should we undertake a fishing expedition, or do something about the strangers who’ve come to town?) is if you decide to hold a discussion, and verbal conversation is supposed to be brief.

Quinns: Brief? It’s tyrannical. Everyone’s allowed to say one thing, going round the table, so no-one can actually reply to anyone else. Which is actually supposed to simulate discussions in communities being frustrating.

Leigh: “Tyrannical”! Again, so harsh. It’s “structured.” Or “disciplined.” I imagine you had a hard time sitting still in school. The game also allows for “contempt tokens”, where if the discussion’s led to an outcome you don’t like, you can register a protest by piling coins (you can just use pennies, or similar) in front of you. If you become alleviated later, you can put the coins back. The coins have no mechanical function, but are a subtle visual marker of the other players’ levels of satisfaction.

Finally, a “discovery” is when you decide you’ve found a new element for the map: A new location, another community, perhaps even another resource. I think. It’s actually sort of tough to tell what qualifies, sometimes, but we’ll discuss that later.

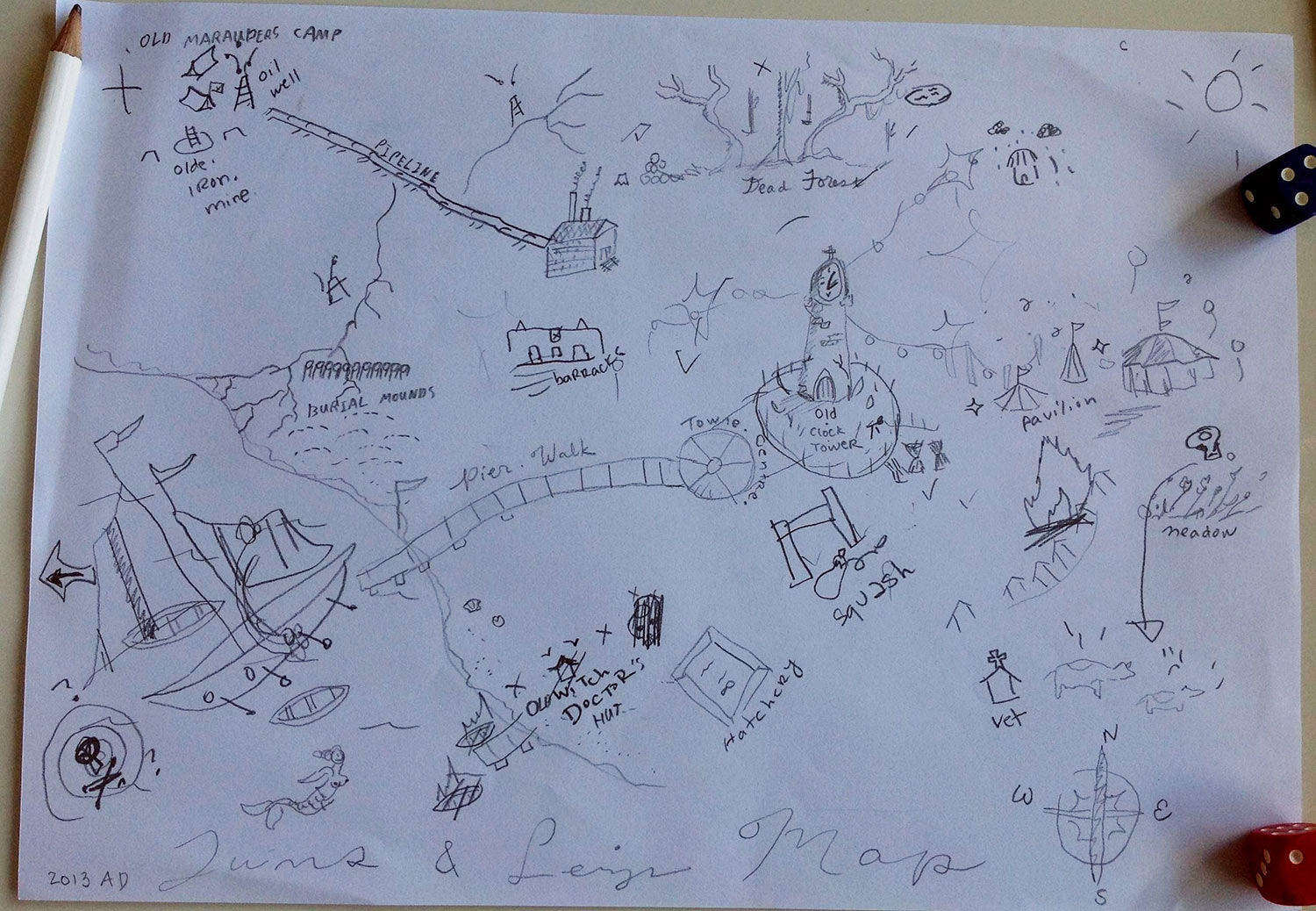

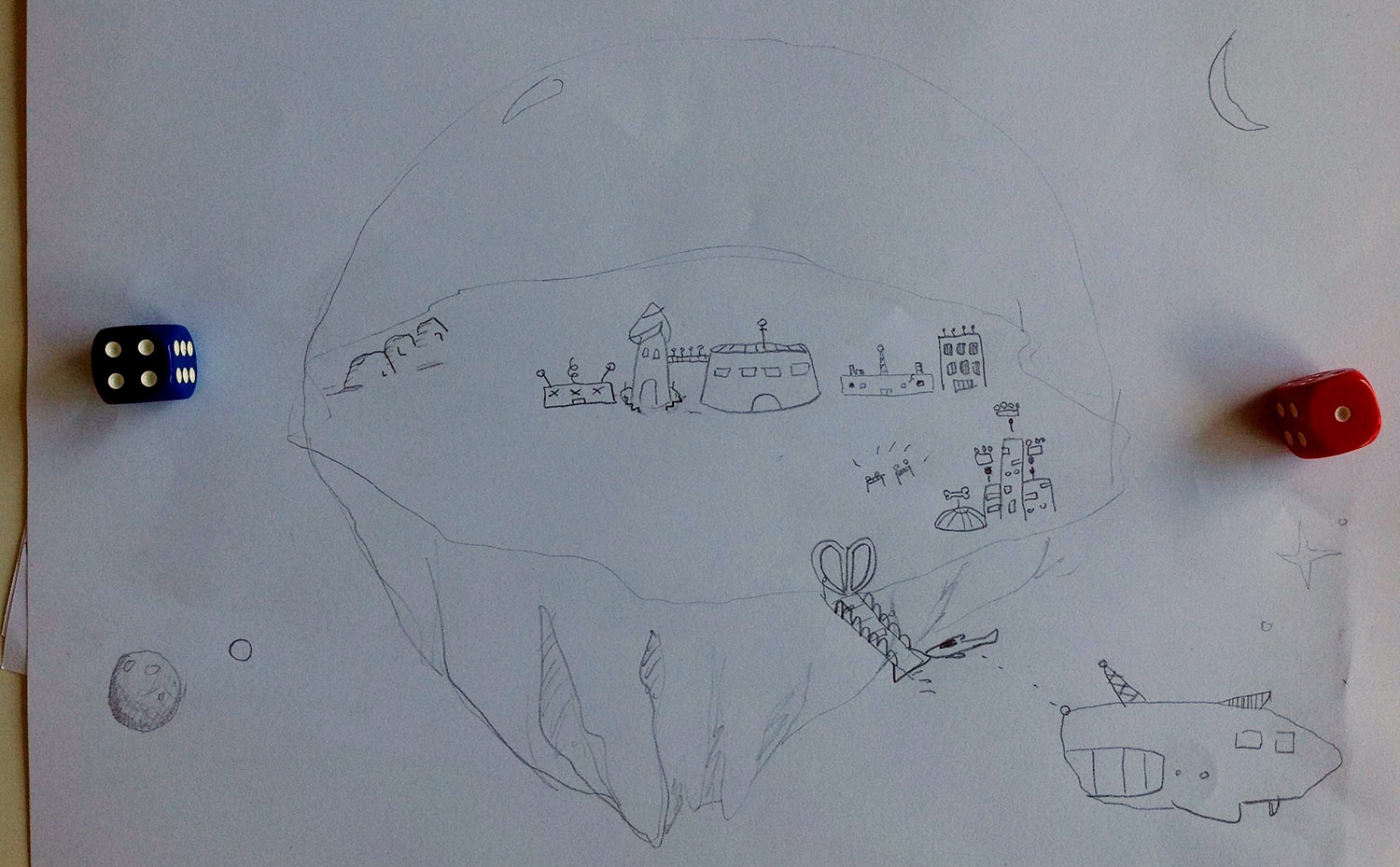

Quinns: Phew! OK, that’s all the rules. Now, let’s definitely discuss the game through the monsterpieces we created. This was game #1:

Quinns: At this point we didn’t know that we weren’t supposed to write on the map. But what I love about this one is that you can actually SEE your attention span drifting. I think the first thing you drew was the clock tower. The last thing was that huge boat and the “SQUASH” plantation.

Leigh: I admit my affinity for rendering the map in loving detail steeply declined in a direct ratio with my wine consumption and degree of patience. Oil had ruined everything! I was angry about the squash!

We actually played this game across two evenings, to further illuminate my let’s-say volatile concentration. I think one is meant to be able to finish in one sitting, but we’ve never, whether it’s just the two of us or with Paul and Brendan, been able to comfortably do that. Those two had to take a night bus when they played with us.

Quinns: What’s odd is that despite our waning attention, the stories our games told are all pretty great! In this one our community had a dire need for firewood and food, but through constant interrogation by the game’s deck, the story that emerged was one of the community’s triumvirate of leadership, and how their children were actually tasked with a pretty important job within the community- performing to keep this people’s story and history alive.

AND THEN OIL HAPPENED. We found an abandoned oil pipeline, and began siphoning out of the earth and towards our community as a replacement for firewood. Except then it started leaking. And poisoning everybody. And being weaponised.

Leigh: In the end, the war over resources and the hunger for technology gutted the land, and the adults abandoned their children. In the end, the Frost Shepherds were THE FEAR AND GREED THAT DIVIDES US ALL.

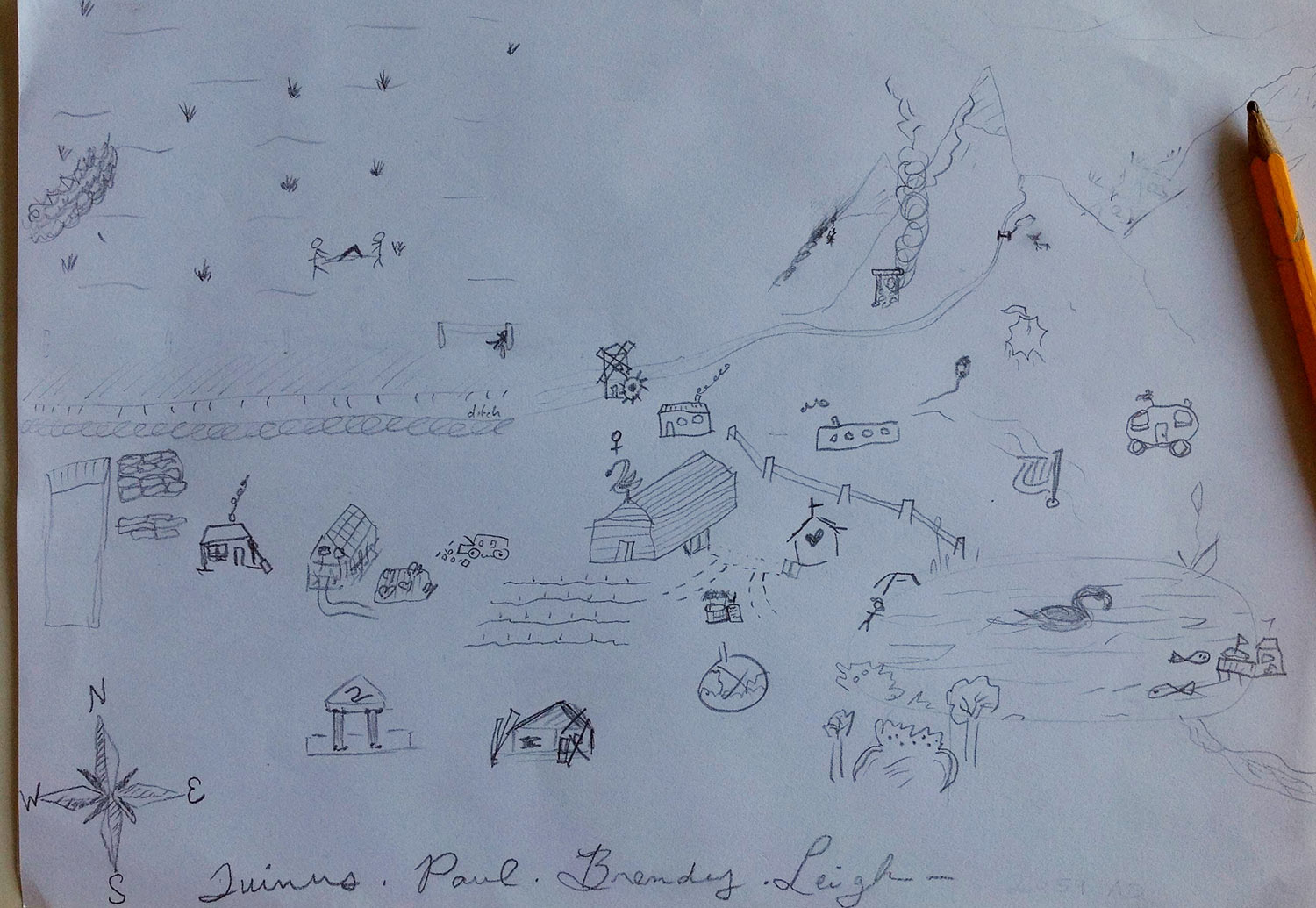

Quinns: Right. And the story of the second game was even cooler! This was you, me, Paul and Brendan’s effort:

Leigh: …All I remember is the conflict among the Swan People, the Deer People… were there Termite People? I don’t remember. In the end the Volturi of the Animal People… you know, the ruling council of clerics… came… I don’t remember, Quinns.

Quinns: Mostly I remember Brendan, prompted by a card, deciding that “the purpose of children in our society” was to recover corpses from the bog. Then we were all so horrified he rapidly retconned that to “No okay their job is to just f**king be kids and hang out.”

Leigh: Ha. Oh yeah! There were some great Brendan Moments in that game.

Quinns: But I want to get to the bottom of why this game is so tiring, and I’ve got a couple of theories for you to pick at. One is that roleplaying games are always fun because they’re about a kind of… emotional frottage. You’re telling a story with your friends, it’s alive, it’s surprising, and you’re connecting in wild and unexpected ways. Monsterhearts, which we reviewed last time (and is actually by the same designer), had a whole section in the manual about keeping the story feral.

Here? It’s willfully antisocial. On your turn, everyone watches and expects you to be interesting, but ultimately you force the story forward alone, while it’s maddeningly hands-off for everybody else.

Leigh: I like this game more than you do. I think a community-focused game is an impressive thing to have exist in a medium that’s usually individualistic, designed to allow people to show off or mess with one another. I think the tension I feel when I play — about the role of the self within the group, or within the partnership — is appropriate for a game with these themes.

But I admit, The Quiet Year began to wear off on me over time, and I think it’s because I tended to feel drawn in too many directions. Importantly, the game cards usually offer you a choice between two outcomes with similar catalysts — it’ll prescribe that a member of the community leads others into something, for example, but you, assuming it’s your turn, get to decide whether it’s something foolhardy or something inspiring.

I felt a tension with those choices, between a number of warring desires: Do I want to tell the most interesting story possible about this place? What if doing so costs my fellow players the opportunity to pursue a narrative thread they’re clearly interested in? Do I want what’s best for our imaginary population, or am I leaning deep into their suffering to further it? I mean, I basically wanted all of these things: To have a good story, to create an immersive, meaningful place, to entertain and engage with the other players, and to stay within the framework of the rules, and trying to balance all of that was often intellectually fatiguing, resulting in elements on the map left unfinished or forgotten, absurd new avenues wallpapered over them.

Maybe that’s okay and intentional, and you and I are just control freaks and this is less-than-ideal for us. As excited as I am about the concept, the way it tickles my imagination, the way sketching maps of entirely-invented places with complex societies takes me back to a precious time in my childhood — even with all of that, the more we played this game the less I got out of it.

In roleplay there is always something to anticipate, something you hope will happen, and having those desires validated or thwarted and having to adapt is part of what keeps me energized and engaged when I play RPGs. I think my problem with The Quiet Year is it’s too hard to find those moments of gratification, where either my intention or the group’s collaboration feels validated.

Quinns: Exactly. I felt the same way, so for our third game we tried to simply lower the stakes. A game where feelings wouldn’t be hurt, because we would just have fun going completely batshit:

Leigh: We ended up with a city inside a dome on an asteroid, violently misogynistic (“owning” one of the few women available to be viewed would make you a sultan), and obsessively building pornography importers and space-casinos to sustain an economy around lab-bred designer pets. It… actually got pretty dark. Like, it’s the first setting you and I’ve made that I could see someone doing a dystopian novel about.

Quinns: Yes. Intergalactic fascists, stroking lustrous kittens and glittering lizards as they discussed how they could claim more women.

Leigh: And even then, with all the laughing and thinking, and even though we were playing the “short” game (you can play it more briefly by cutting the deck in half, according to the rules), I lost my appetite midway through, when we couldn’t decide how negotiations with a captured slaver could pan out within the ruleset.

Quinns: Right. My other theory of why The Quiet Year didn’t have much staying power with us is that it doesn’t know what it wants. It’s extremely difficult to tell a coherent story, because the abstracted nature of the map, of distances, of facts and priorities, mean that everyone’s tugging their corner of the map in a different direction. It fails as a straight-up game of rebuilding a community, as it expects players to introduce problems whenever things get too easy. I’d even go as far as saying that it doesn’t work as an exercise in frustration, because in every game we played I had to remind people that we’re not allowed to talk, which just made me feel like a twat, because the game didn’t visibly gain anything from our silence. It just gave the evening a gentle kind of toxicity, as if our map had an imperceptible coating of mercury.

But you keep saying that you like The Quiet Year more than I do. The truth is, I like this game! I think it’s fascinating. I just like it more as a gorgeous artifact that can take pride of place in my gaming collection, versus something that I’d recommend people actually buy when there are countless astounding one-shot RPGs out there.

Leigh: There may be a personal taste issue, too. I like having to be creative within constraints, and I tend to feel stressed if the rules have too much flexibility, relying on me to govern and interpret them. And I am terminally individualistic. AND I’m possessed of an incurably steep attention span, so I hesitate to say The Quiet Year strictly “doesn’t work” — there are people I’d recommend it to. And you and I probably won’t play it again, but I could see myself using it to break ice with new people, because it’s so portable, requires so very little to teach and to start.

Quinns: I guess there’s your sales pitch. It’s a roleplaying game where nobody has to play roles, if your friends are the type whose monocles pop out at the thought of pretending to be – say – someone of the opposite gender.

What role do children take in your society, Leigh?

Leigh: Oh dear. You’ve been having a very quiet year yourself, haven’t you?

[The Quiet Year is available as a .pdf, physical copy and gorgeous collector’s edition direct from Buried Without Ceremony.]