Leigh: When you first asked me to do pen and paper roleplaying with you, my first thought was of mans sitting around the table doing spreadsheets about their spaceships. Even though you told me Shooting the Moon was about falling in love, I have to admit I was a little skeptical, you know? Like, “okay, rolling for my stats now, Strength, Intelligence and Hotness”.

When we talked about Tease, we both seemed to feel that that systems, stats, and — all right, I’ll say it, nerdery — bear the odour of un-romance. Yet this isn’t like that.

Quinns: No. Who knew? Shooting the Moon is a game that lets 2 or 3 players coax an honest-to-god love story out of the ether. But then, it’s not really a game about falling in love, is it? It’s a game about falling through the cracks of love. A game of struggle, of heartbreak, and – as the front of the book teases – finding out what you’ll do for love.

Shall I rocket through how it works?

Leigh: Do your thing!

Quinns: HERE WE GO.

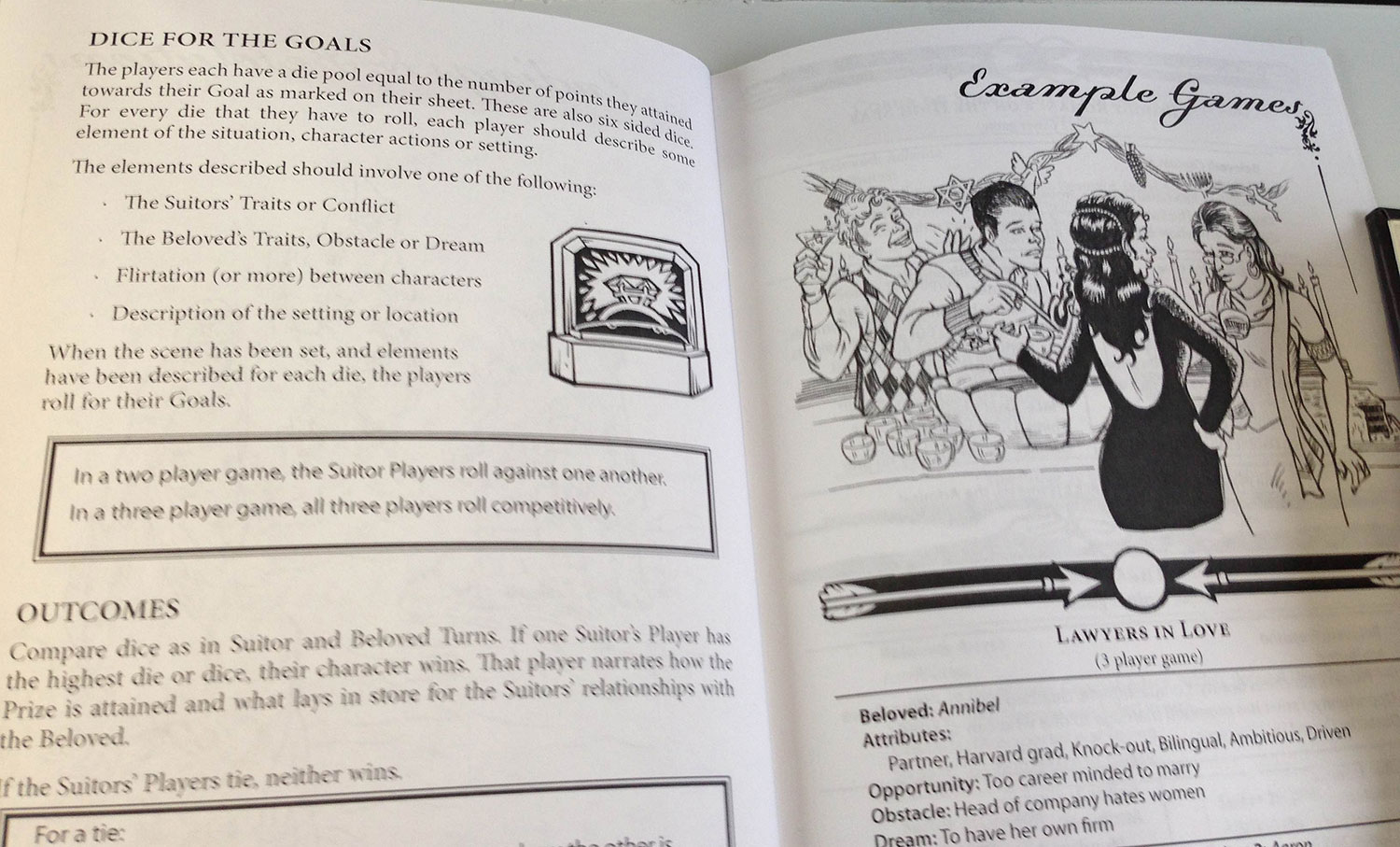

A game of Shooting the Moon starts with you all picking the setting, anything from a piratical Caribbean, to Hogwarts, to a law firm. Wherever you feel like going that evening.

In a 2 player game, you each play a Suitor chasing the heart of a distressingly perfect Beloved. In a 3 player game, the third player actually plays this Beloved. You then take turns creating six traits of the Beloved. Easy.

But THEN you create a synonym and antonym for each of those, which the Suitors proceed to have imposed on them. It immediately sets the game thrumming- if the beloved is Confident, one suitor might be Cocksure, but the other is Timid. If the beloved has an Amazing Car, one of the suitors will be ashamed of his dad‘s saloon that smells irreparably of boogers. Finally, you give this love triangle a pointy tip by deciding on something the Beloved wants even more than love.

Leigh What I like is that the character creation itself is part of the game. Depending on your command of the nuance of language, you can have a lot of fun with Traits via synonyms and antonyms. Is the opposite of “brave” “cowardly,” for example, or is it “cautious?” Is the opposite of “warm” “cold?” I mean, obviously it is, but you could also choose “calculating” or “selfish” or “shy,” all pretty different Traits. You’re setting up complicated friction with the other Suitor just by picking words.

Quinns It also means the suitors are always opposites, which is pretty perfect, eh?

The game itself is almost as simple. On a Suitor’s turn, they take the lead in describing a scene where they win over the Beloved, and it’s the other Suitor’s job to interject with a sentence beginning “As luck would have it…” which ruins everything. Let’s suppose your Arabian merchant was presenting the Beloved with a Ruby. The other Suitor might have a BANDIT ATTACK.

At which point the game grinds to a halt, and the players enter a minigame where dice are gained according to your traits. The player that rolls the highest gets to stamp a new trait on either the Suitor in question, or the Beloved. If your space-age science officer manages to halt the alien mold threatening to devour his lab, you might bolster him with “Quick-thinking”. Fail, and your opponent could give you “Homeless.”

If you’ve got the full complement of 3 players, there’ll also be Beloved turns where they set scenes to challenge one, or even both of the suitors. In all of these scenes the winning player will get points towards the game’s finale. If a Suitor wins, they charm the Beloved. If the Beloved wins, they escape the creepy orbit of the suitors and achieve their goal. Either way, the player who wins narrates the epilogue.

Phew!

Leigh: I should point out playing this feels way less complicated than you make it sound. Usually there’s no faster way to to turn me off than to mouth the words “counting dice,” but I didn’t find it tedious. This was my first time playing a pen and paper game like this, and I found it pretty intuitive. You just do what the book tells you to do, and boom, love knot of tension and intrigue.

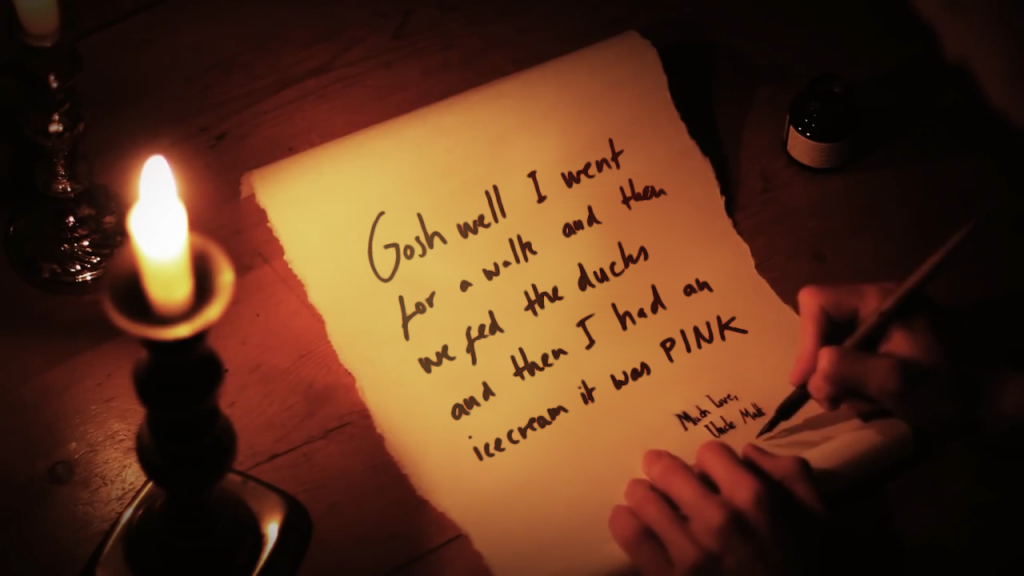

Quinns: Yeah. The speed at which our own game went from about twelve words scribbled on paper to “O gods how will this end” was stunning. Want to describe what happened in our first game?

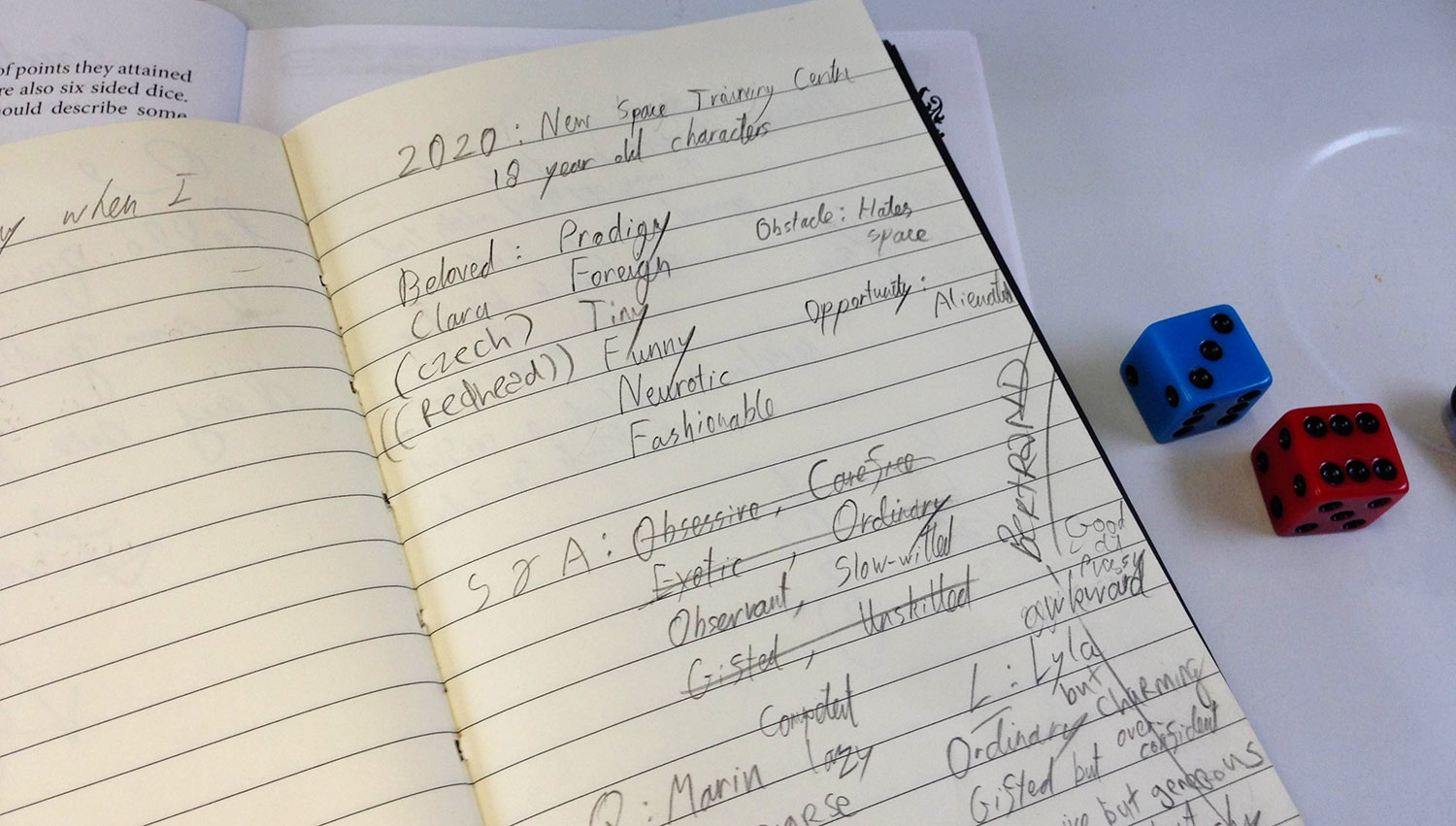

Leigh: So you asked me to come up with the setting — we chose a hyper-modern space program training camp for prodigy high school students. Like high school, but for space geniuses going to space.

Quinns: Which, in retrospect, sounds like we were trying to drain all sexuality from a setting where no sex should be taking place in the first place.

Leigh You know how I normally feel about space romance. Players pressing X to fast-forward through tedious galactic diplomacy to get to the bumping alien bits. But our base was set in a postmodern tropics, like Hawaii in the year 2030 or something. I’m homesick for summer weather here in London, and I thought the raw beauty of sea cliffs, bright, wet flowers and moonlit grottoes would give us a lot to play with. I love making up settings!

I also sketched that setting with our purposes in mind — we wanted to play with high school relationships, so why not a very special school full of star-chasers, the ambitious, the pressured?

Quinns: See, this is what’s wonderful about Shooting the Moon. In theory, you’re in control of everything. In practice, our game ended up this bleak tale of food poisoning, mud, remedial classes and your character practically forcing themselves on the Beloved as an intimidating nurse.

It surprises you, is my point. Despite the fact that we were making it up, I was hanging on every word. That’s insane! And I guess it all comes down to the need to jink around unexpected obstacles.

Leigh Yeah, you’re making it sound awful crude, though! We had a beautiful story. The “obstacle” we gave Clara, our young Beloved, was that she hated space, remember? This rigorous program was her parents’ wish. And while my biology student, Lyla, tried to manipulate the Beloved under the wing of her own ambitions, your earthy, simple-minded Marin patiently and kindly showed her the beauty of the village where he grew up. There was an incredible scene where he took her to the seaside. And I made it rain. And you hid the Beloved away in a cave that only your character knew, and she felt…

Quinns: She felt slightly uncomfortable, made her excuses and LEFT ME IN THAT CAVE because I failed the die roll. And you imprinted the gorgeous Clara with the Fastidious trait, rendering Marin’s grubby charm useless.

The picture on the cover really is apt. It’s storytelling as fencing.

Leigh Yeah. She didn’t like mud, so I ruined your date. And when she ate at your family’s restaurant she got food poisoning and went to my hospital. Which is where Lyla and Clara made love for the first time. What a sexy illness.

Um. Anyway, what I think is good about it is it doesn’t require you to act. You can simply narrate. I mean, I like acting. I went to school for it, which did me no good except for to make me good at roleplaying.

Quinns: Yesss. Which I guess makes the title of “role-playing game” a bit of a misnomer. You don’t have to step into a role. It’s more like being a fictional custodian. When our confused Clara fled her soiled hospital bed–

Leigh FLED is harsh, she enjoyed herself —

Quinns: FLED her hospital bed, to arrive at Marin’s dorm room because she was confused and needed someone stable, I didn’t feel like it was me. I was like Marin’s… father, or something. “Go on, son!”

Leigh But remember the time I forgot that one of my traits was “shy?” And you interrupted some description of a word or action of mine, saying it didn’t seem very shy. So I adapted; I performed the line as someone shy would deliver it. But you still let me do the action, because I acted it believably. That’s a cool example of how the book is so free-form that players can kind of decide on the fly what’s acceptable. There’s a lot of interplay.

Quinns: Yeah. So, the only serious criticism I have of Shooting the Moon is, for a game that would otherwise be a crystalline roleplaying game for newcomers, the rules are atrociously foggy at times. The book starts off as a decent enough guide to roleplaying and character creation, but when it comes to the most gamified part – the gathering of dice pools to resolve the scenes – it’s a trainwreck. After five readthroughs I was still utterly baffled.

With the board games SU&SD usually covers, that’d be doomsday. Here, it’s a speedbump. By the end of our game, you and I had adapted all these tiny house rules and alterations. It’s almost not a game, but a manual for how to play with another human.

Leigh: Yeah. I wonder if the designer recusing herself in that way is intentional, y’know? Because we had to talk, we had to work out some of our own details for the system — which ensures that the richness and pleasure of the relationship story depends on the relationship of the players.

Quinns: Oh man. That’s optimistic.

Leigh: Still, I definitely felt closer to you after we played. It was kinda neat.

I can see, though, that it might be a problem for people coming into this brand-new, who haven’t thought about how to make a game out of a story.

Quinns: So, let me ask you the question that powers SU&SD like a hot dinner. SHOULD THEY BUY IT?

Leigh: Who’s “they?”

Quinns: Them. Over there.

Leigh: Oh. Well, I’d like them to, you know? I want to do more tabletop gaming with friends, and all the games you’ve successfully gotten me into have to do with people talking to one another. I like those ones (and ones where I can pretend to be a spy or where I can turn out to be a traitor and surprise you!) With indie RPGs, I see the potential for conversations to get broader than talk of cards and chits and all of that stuff you and Paul do at the weekends.

Quinns: Yeah. I feel the same way. Except our indie RPG reviews might get a bit restraining-ordery if we always just say YES, MORE, BUY IT. Maybe a better question is who’s this for?

Leigh: People who like story more than systems, experience more than logic. People like me, who like words better than numbers, and want a cool way to be creative and playful with their friends. And pervs. Probably pervs. Not that it’s a bad thing, Quinns, don’t worry.

Quinns: I was going to say a comedy answer, but then I’ve realised there are no comedy answers.

Anybody who wants a love story set in a Welsh coal mine? Anyone who wants to make a passionate drama featuring their own housemates? Anyone who wants to roleplay cramped makeout sessions in the Jefferies tubes of the Starship Voyager?

It’s love. It’s for all of us. Isn’t that incredible?